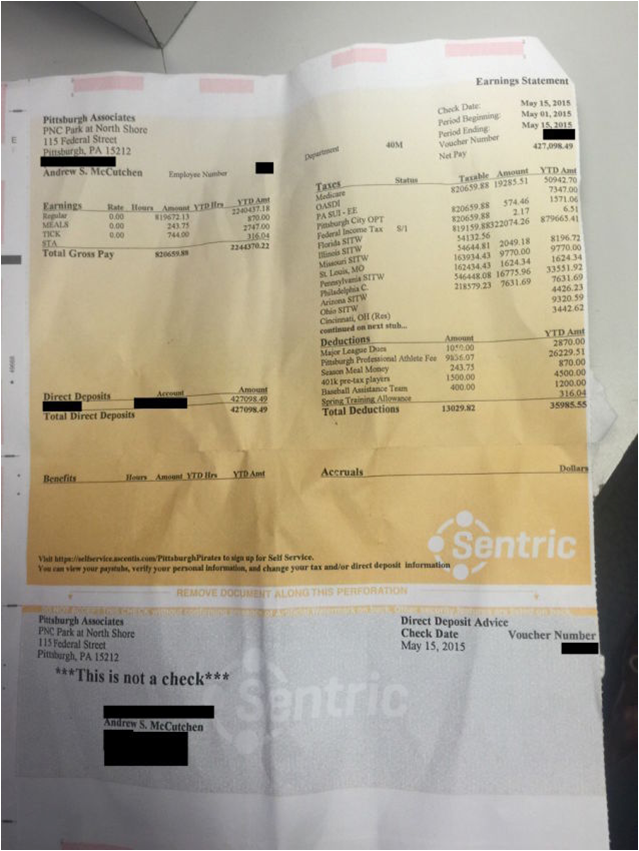

Outfielder Andrew McCutchen (“McCutchen”) of the Pittsburg Pirates left something behind in Chicago after playing the Cubs on May 15, 2015. It seems that his paystub was found in the Wrigley field visitor’s clubhouse according to Reddit user Grassiii, who posted a photo of the paystub which has since gone viral.[1] The information contained on said paystub is extraordinarily interesting and provides a fascinating insight into the paycheck of a professional athlete.

Three years ago McCutchen signed a six year, $51 million deal that pays him approximately $10,208,333.00 per year. McCutchen is the 109th highest paid player in Major League Baseball. The five highest paid players are Clayton Kershaw ($32.5 million), Justin Verlander ($28 million), Ryan Howard ($25 million), Cliff Lee ($25 million), and Zack Greinke ($25 million).[2]

Every two weeks, McCutchen grosses $820,659.88 and nets $427,098.49.

During the month of May, 2015, McCutchen played three games in St. Louis (May 1st, 2nd, and 3rd), four games in Philadelphia (May 11th, 12th, 13th, and 14th), and one game in Chicago (May 15th).

McCutchen paid a lot of different taxes. While he was subject to paying Medicare, Social Security and federal income tax, McCutchen also paid income taxes for states and cities as a result of the so called “jock tax,” which is an income tax levied against visitors to a city or state who earn money in that jurisdiction. Both the State of Pennsylvania and the City of Philadelphia impose jock taxes. Both the State of Missouri and the City of St. Louis impose jock taxes. From the pay stub, here is what McCutchen paid in income taxes to cities and states for playing within their jurisdictions:

State of Missouri $9,770.00

City of St. Louis $1,624.34

State of Pennsylvania $6,710.38

City of Philadelphia $7,631.69

The Jock Tax is an accounting and administrative nightmare for professional athletes. Ryan Losi, CPA and executive vice president of Piascik & Associates, a Glen Allen, Va., indicates that, “NFL players typically file in 10 to 12 jurisdictions. NBA is somewhere between 16 and 20. MLB is somewhere between 20 and 26, and the NHL is between 14 and 16.”[3] Losi said, “[b]ehind every sports star who’s hauling down the big bucks is a keen-eyed certified public accountant quick-stepping through a maze of state and local income taxes imposed on nonresident athletes.”[4]

Taxing states and some cities impose a “jock tax” on visiting professional sports players in one of two different ways. Most use the “duty days” method, which divides the player’s total number of work days during the season by the number of days spent playing in that state or city. A few use the “games played” method, which divides the total number of games in the season by the number played in that state or city.

Unfortunately, no two states calculate their jock tax exactly alike.

Losi further stated that “[t]hey all agree on the fraction; they just don’t agree on what goes into the numerator and the denominator. Some jurisdictions treat practices and OTAs (organized team activities) as a working day. Others say that if you travel but don’t play, that doesn’t count.” All those state filings can make for one doorstop of a tax return.[5]

K. Sean Packard of OFS Wealth in McLean, Virginia specializes in preparing tax returns for professional athletes. He indicated that “there are 21 states” that levy jock taxes. Then you have a bunch of localities like Columbus, Cleveland, Cincinnati, Kansas City, St. Louis, Detroit, Philadelphia and Pittsburgh that assess jock taxes.[6]

But McCutchen can hardly complain. His home state and home city both impose jock taxes. In the City of Pittsburgh the jock tax is called the Nonresident Sports Facility Usage Fee and has been in place since 2005. The city code indicates that: “A license fee equal to 3% of earned income is hereby imposed upon each nonresident who uses a publicly funded facility to engage in an athletic event or otherwise render a performance for which a nonresident receives remuneration.”[7]

But McCutchen can hardly complain. His home state and home city both impose jock taxes. In the City of Pittsburgh the jock tax is called the Nonresident Sports Facility Usage Fee and has been in place since 2005. The city code indicates that: “A license fee equal to 3% of earned income is hereby imposed upon each nonresident who uses a publicly funded facility to engage in an athletic event or otherwise render a performance for which a nonresident receives remuneration.”[7]

Teams pay the city directly and withhold income from players’ checks. So, in the State of Pennsylvania a player is not only taxed at Pennsylvania’s 3.07% state income tax rate, but then Pittsburgh’s 3% flat fee is added for a combined tax rate of over 6%.[8]

However, there is some good news for professional athletes at least with respect to Cleveland’s Jock Tax. The Cleveland Jock Tax was challenged by former Chicago Bears Linebacker Hunter Hillenmeyer (“Hillenmeyer”) (Hillenmeyer v. Cleveland Bd. of Rev., Slip Opinion No. 2015-Ohio-1623[9]) and Indianapolis Colts Center Jeff Saturday (“Saturday”) (Saturday v. Cleveland Bd. of Rev., Slip Opinion NO. 2015-Ohio-1625[10]) in the Supreme Court of Ohio.

In the Hillenmeyer opinion, Ohio’s highest court on April 30, 2015 struck down Cleveland’s so-called “jock tax,” ruling that Cleveland was excessively taxing visiting professional athletes using an illegal method to calculate their tax bills. Cleveland’s unusual tax rule calculates a professional athlete’s taxable income based on how many games an athlete plays in Cleveland. Other cities use a method based on how much time players spend in the city.[11]

Hillenmeyer’s position was simple:

As a nonresident of Cleveland, Hillenmeyer asserts that Cleveland has adopted an unlawful method of computing the amount of his compensation that is subject to its city income tax. The games-played method, he argues, dramatically overstates his Cleveland income, because his compensation as an NFL player includes earnings not only for the games he played, but also for the training, practices, strategy sessions, and promotional activities he engaged in.[12]

Hillenmeyer further challenged the method of tax calculation by Cleveland:

{¶ 16} At the heart of the dispute before us is the method that Cleveland has chosen to allocate the taxable income of nonresident professional athletes. Cleveland imposes a 2 percent tax on the income that is allocable to Cleveland. See Cleveland Codified Ordinances 191.0501. CCA Regulation 8:02(E)(6) sets forth a games-played method to allocate the income of a nonresident professional athlete such as Hillenmeyer. This means that Cleveland taxes the one game that Hillenmeyer played in Cleveland each year in proportion to the total number of games the Bears played during the year (approximately 20 preseason and regular season games in a non-playoff year). Under this methodology, a visiting football player who travels to Cleveland for a single game out of a 20-game season will have one twentieth (5 percent) of his income allocated to Cleveland and then taxed at 2 percent. The Cleveland tax administrator asserts that the games-played method “properly apportions player salaries since the plain language of both [the CBA and the standard player contract] ties a player’s contract salary to one thing—games played.”[13]

The Court thought the duty days approach was the proper method of calculation:

{¶ 17} Nevertheless, except for Cleveland, municipalities that have chosen to tax professional athletes do so on the basis of the allocation offered by Hillenmeyer—the “duty-days” approach. In this approach, the numerator represents the number of days spent in the taxing city: in this case, two days for one game. The record shows that Hillenmeyer had 157 duty days in 2004, 165 in 2005, and 168 in 2006. When these numbers are used as the denominators to represent the total number of work days, Cleveland would have been allocated approximately 1.27 percent of Hillenmeyer’s income in 2004, 1.21 percent in 2005, and 1.19 percent in 2006. Under the duty-days method, Hillenmeyer claims he is entitled to refunds of $253 for 2004, $359 for 2005, and $4,450 for 2006.[14]

The Ohio Supreme Court, overturning decisions by the state’s tax appeals board, ruled that Cleveland’s taxing method was illegal.[15]

Here’s the key passage from one of the two opinions handed down:

Due process requires an allocation that reasonably associates the amount of compensation taxed with work the taxpayer performed within the city. The games-played method results in Cleveland allocating approximately 5 percent of Hillenmeyer’s income to itself on the basis of two days spent in Cleveland. By using the duty-days method, however, Cleveland is allocated approximately 1.25 percent based on the same two days. By using the games-played method, Cleveland has reached extraterritorially, beyond its power to tax. Cleveland’s power to tax reaches only that portion of a nonresident’s compensation that was earned by work performed in Cleveland. The games-played method reaches income for work that was performed outside of Cleveland, and thus Cleveland’s income tax violates due process as applied to NFL players such as Hillenmeyer.[16]

In essence then the Court found that although Cleveland has the right to tax the compensation earned by a nonresident professional athlete for his work performed in Cleveland, the city’s application of its games-played method of allocating income violates the due-process rights of NFL players.[17]

Accordingly, Hillenmeyer will be granted a refund of approximately 75% of the Cleveland income tax withheld by the team.[18]

In Hillenmeyer, the Court also considered whether the exception for professional athletes and entertainers under the occasional-entrant rule (former R.C. 718.011(B)) violated constitutional Equal Protection. This occasional-entrant rule exempts individuals from municipal income tax on their wages if they worked less than 12 days in the municipality. Applying a more liberal standard, the Court found that because the events for which the athletes and entertainers are paid require a much higher public burden, such as for police protection, traffic, crowd control, and other public services, the city had a rational basis for treating these taxpayers differently. Accordingly, the exception from the occasional-entrant rule did not violate the player’s Equal Protection rights.[19]

Saturday’s case was even more egregious. Cleveland taxed Saturday, a former center for the Indianapolis Colts, for a single game in Cleveland in 2008. In his case, he never stepped foot in the city of Cleveland but missed that game due to an injury. He owed money anyway because the city’s regulation applied the tax to any game in Cleveland “in which the athlete was excused from playing because of injury or illness.”[20] The Court found that the Cleveland income tax was only imposed on compensation earned for work done or services performed or rendered in the City of Cleveland.[21] Since Saturday did not perform any services in Cleveland that year, and actually reported to work in Indianapolis on game day, the Court ruled that the tax was not authorized under Cleveland’s Income Tax Ordinance and Regulations. Accordingly, Saturday was granted a full refund.[22]

Cleveland faces significant fallout from these two decisions as professional athletes who paid Cleveland income tax on the games-played method probably will be filing refund claims. Players for teams visiting the Browns will be entitled to a refund similar to Hillenmeyer of approximately 75% of the tax paid. But even Browns players who are not Cleveland residents have a significant refund opportunity. Presumably, these players have paid Cleveland tax on 50% of their revenue because half the games played were in Cleveland. Converting to the duty-days method, the player would owe Cleveland tax for days reporting to the Browns practice facility in Berea, which presumably would be significantly more than 50% of the total days the player reported to work. [23]

In the Hillenmeyer case, the defendants’ lawyers filed on May 11, 2015 a Motion for Reconsideration of Decision on the Merits.[24]

[1] http://deadspin.com/lets-take-a-look-at-andrew-mccutchens-pay-stub-1706188663

[2] http://sportsmockery.com/2015/05/andrew-mccutchen-left-his-pay-stub-at-wrigley-field/

[3] http://www.bankrate.com/finance/taxes/taxes-cost-professional-athlete.aspx

[4] http://www.bankrate.com/finance/taxes/taxes-cost-professional-athlete.aspx

[5] http://www.bankrate.com/finance/taxes/taxes-cost-professional-athlete.aspx#slide=3

[6] http://www.usatoday.com/story/sports/2015/04/13/tax-day-april-15-accountant-pro-athletes/25742385/

[7] http://www.usatoday.com/story/sports/2015/04/13/tax-day-april-15-accountant-pro-athletes/25742385/

[8] http://www.usatoday.com/story/sports/2015/04/13/tax-day-april-15-accountant-pro-athletes/25742385/

[9] http://www.supremecourt.ohio.gov/rod/docs/pdf/0/2015/2015-Ohio-1623.pdf

[10] http://www.supremecourt.ohio.gov/rod/docs/pdf/0/2015/2015-Ohio-1625.pdf

[11] http://blogs.wsj.com/law/2015/04/30/ohio-high-court-strikes-down-clevelands-jock-tax/

[12] Hillenmeyer v. Cleveland Bd. of Rev., Slip Opinion NO. 2015-Ohio-1623.

[13] Id.

[14] Id.

[15] http://blogs.wsj.com/law/2015/04/30/ohio-high-court-strikes-down-clevelands-jock-tax/

[16] http://blogs.wsj.com/law/2015/04/30/ohio-high-court-strikes-down-clevelands-jock-tax/

[17] Hillenmeyer v. Cleveland Bd. of Rev., Slip Opinion NO. 2015-Ohio-1623.

[18] http://www.bdblaw.com/municipal-income-tax-clevelands-method-of-imposing-jock-tax-struck-down-by-ohio-supreme-court/

[19] http://www.bdblaw.com/municipal-income-tax-clevelands-method-of-imposing-jock-tax-struck-down-by-ohio-supreme-court/

[20] http://blogs.wsj.com/law/2015/04/30/ohio-high-court-strikes-down-clevelands-jock-tax/

[21] Saturday v. Cleveland Bd. of Rev., Slip Opinion NO. 2015-Ohio-1625

[22] http://www.bdblaw.com/municipal-income-tax-clevelands-method-of-imposing-jock-tax-struck-down-by-ohio-supreme-court/

[23] http://www.bdblaw.com/municipal-income-tax-clevelands-method-of-imposing-jock-tax-struck-down-by-ohio-supreme-court/

[24] http://www.sconet.state.oh.us/pdf_viewer/pdf_viewer.aspx?pdf=766922.pdf