By Martin J. Greenberg and Patrick Hankins

I. The Basics: What is Esports?

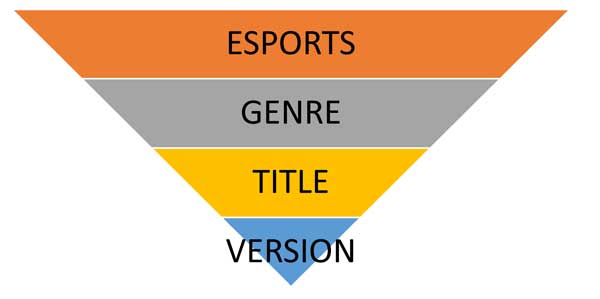

“Esports” is an umbrella term for organized competitive video gaming. Like traditional sports, esports involves a variety of different games that can be separated by discipline. Different disciplines, better known as genres, consist of various video game titles which occasionally have different versions. For most titles, the most current version is played, but there are some instances where older iterations of games are played. Below, the Call of Duty franchise is used as an example of these nuances:

These tables briefly define a selection of prominent e-sports genres, their descriptions and some related titles.

These tables briefly define a selection of prominent e-sports genres, their descriptions and some related titles.

| Genre | First/Third Person Shooters (FPS/TPS) | Multiplayer Online Battle Arena (MOBA) | Real Time Strategy (RTS) |

| Description | Shooting games, distinguished by viewmodel perspective (first or third person) or by the game’s objective. Teams can vary in size. | Two opposing teams compete to destroy each other’s base. Each team consists of five players assuming five different roles to work together to attack other players, complete objectives, and destroy defensive structures to breach the base. | RTS games are strategy games where players’ simultaneously act instead of taking turns. RTS games usually require competitors to gather resources, build units and structures, then control these units to destroy their opponent’s assets. |

| Examples | Call of Duty, Counter-Strike, Quake, Overwatch | League of Legends, Dota 2 | Starcraft |

| Genre | Fighting Games (FGC) | Battle Royales (BR) | Sports Games |

| Description | Fantastic simulated combat. Players chain attacks together through button sequences. The acronym “FGC” stands for Fighting Game Community, as some consider the FGC an independent, separate competitive gaming entity. | Players individually, in duos, or groups are airdropped into a large playing area where they must scavenge for weapons and materials in order to eliminate other players while running away from a gradually shrinking playing area. Players who are caught outside the playing area continually lose health points to moti | Simulated stick and ball sports games. Depending on the rules of a league, individuals may control single players or the entire team. |

| Examples | Street Fighter, Mortal Kombat | Fortnite, PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds, Apex Legends | NBA2k, Madden |

II. A Brief History

Baseball claims sandlots, football has school yards. Esports started in crowded arcades and on the living room couch. The beginning of esports can be traced back nearly fifty years when the first video game console was marketed and sold for home use.[1] From there, the need to best other players moved to arcade consoles to claim the highest score against local competition.[2] Through arcades, video game publishers took note of their games’ popularity and even hosted tournaments. Atari, publisher of Space Invaders, hosted arguably the first large competitive video gaming event in 1980: a tournament that attracted 10,000 players.[3] Throughout the 1980s, competitive arcade play and tournaments would continue to be hosted at various production levels. As technology continued to advance, the video game industry would also develop at a rapid pace, soon allowing players to compete with others from all over the world.

Esports’ current boom is rooted in the relationship between the Internet and video gaming. The early 1990s would usher in an era of online video games. Initial multiplayer competitive gaming existed casually between college students who formed teams and faced each other recreationally.[4] However in the late 90s, competitive gaming would adopt characteristics more reminiscent of current day esports. In 1997, the “Red Annihilation,” a Quake event, took place. [5] This event, which some regard as one of the first “true” esports competitions, started with online preliminaries that attracted over 2000 entrants who battled one-on-one for one of sixteen spots at an in-person bracket tournament at the year’s Electronic Entertainment Expo in Atlanta, Georgia.[6] The winner of the tournament received the grand prize, the Quake programmer’s Ferrari.[7] Within the decade, competitive gaming spectacles would grow even larger and witness the birth of the first esport league, the Cyberathlete Professional League (CPL) – a herculean effort to bring legitimate, organized esports to the masses.[8] The CPL would introduce traditional sports mainstays like play-by-play commentary in 1999 and live stream broadcasting in 2001.[9] Video games featured in the CPL like “Counter-Strike” and “Quake” are still esports mainstays today.

Esports’ current boom is rooted in the relationship between the Internet and video gaming. The early 1990s would usher in an era of online video games. Initial multiplayer competitive gaming existed casually between college students who formed teams and faced each other recreationally.[4] However in the late 90s, competitive gaming would adopt characteristics more reminiscent of current day esports. In 1997, the “Red Annihilation,” a Quake event, took place. [5] This event, which some regard as one of the first “true” esports competitions, started with online preliminaries that attracted over 2000 entrants who battled one-on-one for one of sixteen spots at an in-person bracket tournament at the year’s Electronic Entertainment Expo in Atlanta, Georgia.[6] The winner of the tournament received the grand prize, the Quake programmer’s Ferrari.[7] Within the decade, competitive gaming spectacles would grow even larger and witness the birth of the first esport league, the Cyberathlete Professional League (CPL) – a herculean effort to bring legitimate, organized esports to the masses.[8] The CPL would introduce traditional sports mainstays like play-by-play commentary in 1999 and live stream broadcasting in 2001.[9] Video games featured in the CPL like “Counter-Strike” and “Quake” are still esports mainstays today.

Simultaneously, the international esports market experienced a similar esports renaissance in the late 1990s.[10] By 2000, South Korea, who would later be a world leader in esports, had established the infrastructure, a culture for communal PC use in “PC bangs” (essentially internet cafes), and a government that created a regulatory body that oversaw esports thus providing an environment to develop esports into an activity worthy enough to be deemed a “pastime.” [11]

In the 2010s, esports ascended to a global phenomenon through internet live streaming services. Websites like Twitch.TV brought the atmosphere of stadiums, PC bangs, and convention halls to computer monitors.[12] Esports leagues owe livestreaming for its monetization potential and popularity: livestreaming increases engagement, player count, and monthly revenue of esports titles.[13] In 2019, esports is projected to generate $1.1 billion from a worldwide audience of 454 million viewers.[14] This year alone, sponsors have collectively spent $456.7 million to reach esports’ young audience.[15] Among viewership numbers, 33% are 18-24 and 42% are 25-35 years old.[16] To reach this audience, more mainstream sponsors such as Geico, State Farm, Nissan, Axe, Toyota, T-Mobile, and Coca-Cola have invested in leagues. Though esports’ current revenue streams are dominated by sponsorships, media rights are predicted to eclipse them in three years and become the largest source of revenue.[17] The growth of esports’ audience motivates improvements in league infrastructures.

In the 2010s, esports ascended to a global phenomenon through internet live streaming services. Websites like Twitch.TV brought the atmosphere of stadiums, PC bangs, and convention halls to computer monitors.[12] Esports leagues owe livestreaming for its monetization potential and popularity: livestreaming increases engagement, player count, and monthly revenue of esports titles.[13] In 2019, esports is projected to generate $1.1 billion from a worldwide audience of 454 million viewers.[14] This year alone, sponsors have collectively spent $456.7 million to reach esports’ young audience.[15] Among viewership numbers, 33% are 18-24 and 42% are 25-35 years old.[16] To reach this audience, more mainstream sponsors such as Geico, State Farm, Nissan, Axe, Toyota, T-Mobile, and Coca-Cola have invested in leagues. Though esports’ current revenue streams are dominated by sponsorships, media rights are predicted to eclipse them in three years and become the largest source of revenue.[17] The growth of esports’ audience motivates improvements in league infrastructures.

Esports’ current challenge is marrying its popularity with accessibility. Tournament organizers and broadcasters compete by boasting unparalleled viewing experience from adopting a variety of new technology from on-demand player perspectives to augmented reality all in pursuit of a whole new generation of sports fanatics and their attention. In return, esports fans expect a commitment to the organic integrity that brought video games from the arcade to stadiums.

Esports’ current challenge is marrying its popularity with accessibility. Tournament organizers and broadcasters compete by boasting unparalleled viewing experience from adopting a variety of new technology from on-demand player perspectives to augmented reality all in pursuit of a whole new generation of sports fanatics and their attention. In return, esports fans expect a commitment to the organic integrity that brought video games from the arcade to stadiums.

The next frontier for esports poses a new challenge: what should a tailor-made esports experience look like?

III. The Current State of Esports Venues

Esports tournament organizers currently turn to traditional sports stadiums, convention halls, and theatres to accommodate their needs for major, championship-level tournaments.[18] The few dedicated venues built by video game publishers currently accommodate, at most, up to 1000 fans and offer food and merchandise sales. All professional esports leagues experience a disparity of attendance between regular season competition and a monumental increase during playoffs. To avoid the need to outsource playoff operations to larger venues, developers and league operators should consider dedicated, modular facilities that cater to the needs and desires of the modern gamer and take video games to the next level.

The Varying Effects of Publisher Control on Investment, Tournament Organizers, and Competition Venues

In the United States, two regulatory philosophies dominate esports: laissez-faire licensing for tournament organizers or tightly controlled, franchised leagues.[19] An all-encompassing term, “esports” umbrellas all organized competitive video games; however, all game titles are treated as separate.

Two of world’s most premier esports titles, Counter-Strike: Global Offensive (CS:GO) and Dota 2 are published by Valve Corporation (Valve) who favors the laissez faire approach to producing esports events. This approach is characterized by liberal title licensing and a general lack of centralized, uniform rules for tournament organizers-Valve games retain some of the soul of esports’ humble beginnings. However, Valve retains control over the tournaments it chooses to sponsor but gives free reign to unassociated, un-partnered tournament organizers to implement independent rules, media platforms, and locations for their own events.[20] Though this approach has presented viewers with a variety of options to watch their favorite games, it has also produced inconsistent eligibility rules and scheduling conflicts amongst different leagues.[21]

One of the most noteworthy incidents highlighting eligibility inconsistency was the 2015 match-fixing scandal of former CS:GO team iBuyPower (iBP). Valve initially chose to indefinitely ban (with the possibility of review) four of the five players involved in the betting scandal from competing in their sanctioned tournaments.[22] Most tournament organizers followed suit amidst fears of being held ineligible for sanctioned major tournament selection. Roughly a year later, Valve released a statement upholding the ban.[23] In their independent review, the four players were unbanned from competitive play by leading third-party tournament provider, ESL who, after updating its rules in accordance to non-Valve guidelines, believed an unban of match fixers before the 2015 ruling echoed the will and desire of the CS:GO community.[24] ESL’s decision was not the norm: it was speculated that most tournament organizers were hesitant to act against Valve’s decision because of the “major championship” system (Majors) the company offers. Majors are biannual tournaments in which Valve selects a tournament organizer to host a Valve sponsored, world-cup-like tournament that crowns the best team in the world. Aside from fan excitement and increased viewership, Majors are an opportunity for tournament organizers (TOs), venue owners, and broadcasters to demonstrate their abilities to create a compelling storyline and showcase new technology to attract more hosting contracts.[25]

A prime example of the benefits Valve’s approach offers, Cologne, Germany’s LANXESS arena has become known as an elite venue in the professional Counter-Strike scene. In 2019, the arena hosted its fifth ESL CS:GO tournament within six consecutive years. Since 2016, the LANXESS has sold out its CS:GO tournaments and the arena experience has become so memorable within the CS:GO community that the arena is affectionately referred to as the “Cathedral of Counter-Strike.”[26] In addition, Cologne has become a name synonymous with premium quality Counter-Strike.

Valve’s philosophy is not a pure laissez faire exercise. Though Valve permits a free market for organizers to host tournaments with its IP, the publisher retains an ability to designate tournaments as “majors” which benefit from their financial support and public promotion. Valve’s system allows for grass-roots organizers and venues to attract viewership, but only major tournaments are truly considered the gold standard of Valve events. Majors’ prestige stem from Valve’s lack of widespread TO support: Valve is not available as a partner for TO’s and venues who seek a long-term relationship. The unpredictability of when Valve decides to use its influence alongside its loose organizational requirements has made sponsorships inconsistent – Valve has no year-round sponsorships because of the presumption that a potential TO partner will cause them to award exclusive broadcasting rights.[27] As a result, in true laissez-faire fashion, investment around Valve games is best exercised in teams’ expansion over multiple game titles and securing entity-based sponsorships. Reasoning for this approach is simple: the more reach an esports team has in the space, the more interest brands have in sponsoring that team.

In stark contrast, other major developers’ complete control over their esports operations has fueled and attracted franchising. Two titles utilizing control for the sake of professionalism are Riot Games’ League of Legends (League) and Activision-Blizzard’s (Blizzard) Overwatch. Both developers have established American-based, franchised leagues that require a multi-million-dollar fee as well as agreeing to be held to the league’s guidelines. Though Blizzard’s Overwatch League is the first esport to have city-based, franchised teams, Riot’s League of Legends Championship Series (LCS) is the model for all publisher-controlled leagues.[28] Even prior to adopting franchising, Riot exercised an “iron fist” over the LCS by implementing a ruleset that governed both players and organizations. Under this system, Riot retains complete control over who participates in the LCS and the expectations of conducts in the LCS. There are “no contemplated process for investigations or punishment proceedings in the LCS rulebook” that requires Riot to offer players or organizations a reason for their decisions.[29] Though Riot elects to uses this method to balance business interests and protect the integrity of competition, then-existing uncertainties for organizations formerly kept investment away from the LCS.[30]

To address long-term investing concerns, franchising was used to quell concerns surrounding publisher-controlled leagues. Starting in its 2018 season, Riot implemented a franchise system for the North American LCS (the European series is implementing their own version of franchising in 2019 [31]), allowing franchises to act without fear of impermanence. Franchise selection of the LCS is retained by Riot, who sets the rigorous standard for selection.[32] Under a franchised LCS, teams may elect to use revenue sharing for their franchise fees and players now have access to a Players’ Association.[33] Riot’s efforts centralized around the LCS are based on the desire to attract brands that want to effectively profit off a young, valuable sporting demographic.[34]

To address long-term investing concerns, franchising was used to quell concerns surrounding publisher-controlled leagues. Starting in its 2018 season, Riot implemented a franchise system for the North American LCS (the European series is implementing their own version of franchising in 2019 [31]), allowing franchises to act without fear of impermanence. Franchise selection of the LCS is retained by Riot, who sets the rigorous standard for selection.[32] Under a franchised LCS, teams may elect to use revenue sharing for their franchise fees and players now have access to a Players’ Association.[33] Riot’s efforts centralized around the LCS are based on the desire to attract brands that want to effectively profit off a young, valuable sporting demographic.[34]

Riot established its first fully-owned studio in 2016 for its broadcasts of the North American League Championship Series (NA LCS).[35] Initially, the venue was established to incentivize passionate fans to attend weekly matches in hopes that they would meet their favorite players and teams. In the venue, the publisher hung up pennants honoring past champions and color-coordinated stage lighting with teams’ colors. On broadcast, Riot’s studio is presented as the Mecca for any die-hard League fan: the audience adds palpable excitement to ordinary regular season matchups, the lighting and décor satisfies any gamer’s fantasy of how a dedicated esports stadium should look – enter, the Battle Arena.

In their 2017 studio update, Riot considered and responded to fans’ desires. Riot installed larger screens and more comfortable seating. All walkways in the venue were widened so that more fans could approach the stage to meet their favorite players or head to purchase merchandise or food. Recognizing fans’ association of professional League with the Battle Arena, Riot constructed a modular stage that could serve as the setting for all their extra content including analyst insights and player interviews.

In their 2017 studio update, Riot considered and responded to fans’ desires. Riot installed larger screens and more comfortable seating. All walkways in the venue were widened so that more fans could approach the stage to meet their favorite players or head to purchase merchandise or food. Recognizing fans’ association of professional League with the Battle Arena, Riot constructed a modular stage that could serve as the setting for all their extra content including analyst insights and player interviews.

Next, Riot’s strategy turned to nonendemic advertising. As of 2018 Jersey Mike’s and State Farm are official partners of the NA LCS. The scope of Jersey Mike’s sponsorship includes fan-related activations as well as providing all the cheerboards in the stadium.[36] State Farm sponsors expert segments and the analyst desk which is shown on broadcast before and after every match.[37] For both Jersey Mike’s and State Farm, the NA LCS sponsorship is a foray into the esports space. Both companies targeted League as their first title because of the size of the game’s fandom as well as Riot’s ability to provide a consistent, stable location to reach their audience.

Blizzard’s Overwatch League (OWL) utilizes traditional sports’ city-based franchising to attract non-endemic sponsors and team owners. Requiring a $20 million franchise fee in 2017, OWL’s inaugural season consisted of twelves teams, many backed by familiar sports names like the Kraft Group and public figures like the Kroenkes.[38] OWL was able to attract proven names in sports despite a unprecedented franchise fee because of how it deviates from other leagues (like the LCS) in its potential for growth and consistency; as part of its investment strategy, OWL will continue to adopt traditional sports dynamics such as requiring teams to host opposing teams at home and travel to other home locations. By undertaking tournament organization as well as franchising, ticket sales, merchandising, and concession, OWL intends to keep minimize third party profits – a growing trend in the current state of esports.[39]

Blizzard’s Overwatch League (OWL) utilizes traditional sports’ city-based franchising to attract non-endemic sponsors and team owners. Requiring a $20 million franchise fee in 2017, OWL’s inaugural season consisted of twelves teams, many backed by familiar sports names like the Kraft Group and public figures like the Kroenkes.[38] OWL was able to attract proven names in sports despite a unprecedented franchise fee because of how it deviates from other leagues (like the LCS) in its potential for growth and consistency; as part of its investment strategy, OWL will continue to adopt traditional sports dynamics such as requiring teams to host opposing teams at home and travel to other home locations. By undertaking tournament organization as well as franchising, ticket sales, merchandising, and concession, OWL intends to keep minimize third party profits – a growing trend in the current state of esports.[39]

OWL plays its regular season games at the Blizzard Arena in Burbank, California. The Blizzard Arena takes the place of the now New York based “Tonight Show” and boasts an 11,000 square-foot sound stage that has a 13,000-pixel LED wall.[40] Taking the place of a soundstage, the Blizzard Arena is subject to spatial limitations: the venue only seats 450 attendees and concessions are limited.[41]

In the 2019 season, OWL is focused on expanding its league to include eight new expansion teams and increasing existing franchises’ exposure to local markets.[42] During the offseason, OWL teams are hoping to stir up excitement in nonendemic settings to encourage attendance during a rivalry weekend to be played in stadiums across the country later in the year in franchises’ respective cities. For example, in Los Angeles, OWL team L.A. Valiant attended and hosted a meet-and-greet during an esports themed L.A. Kings Night to promote their match against cross-town rivals the L.A. Gladiators to be played in L.A. Live, the entertainment complex that houses the STAPLES Center.[43] Undoubtably, this weekend will also be a test to see if localized arenas are viable to reach the league’s 2020 target of localized play in home markets.[44]

In the 2019 season, OWL is focused on expanding its league to include eight new expansion teams and increasing existing franchises’ exposure to local markets.[42] During the offseason, OWL teams are hoping to stir up excitement in nonendemic settings to encourage attendance during a rivalry weekend to be played in stadiums across the country later in the year in franchises’ respective cities. For example, in Los Angeles, OWL team L.A. Valiant attended and hosted a meet-and-greet during an esports themed L.A. Kings Night to promote their match against cross-town rivals the L.A. Gladiators to be played in L.A. Live, the entertainment complex that houses the STAPLES Center.[43] Undoubtably, this weekend will also be a test to see if localized arenas are viable to reach the league’s 2020 target of localized play in home markets.[44]

Esport title publishers will always have a voice in dictating the direction of an esport. Aside from the physical differences between esports and traditional sports, legal ownership over the sport most definitively separates the two. As esports increasingly mirrors tradition sports, they will soon have legal issues that surround real estate deals for stadiums and player housing.[45] The success of a particular franchising model will define an era in esports and the development of publisher-backed esports venues.

Esport title publishers will always have a voice in dictating the direction of an esport. Aside from the physical differences between esports and traditional sports, legal ownership over the sport most definitively separates the two. As esports increasingly mirrors tradition sports, they will soon have legal issues that surround real estate deals for stadiums and player housing.[45] The success of a particular franchising model will define an era in esports and the development of publisher-backed esports venues.

The Vegas Method: Adapting Existing Spaces for Millennials’ Tastes

To cater to younger demographics’ changing entertainment preferences, multiuse facilities have converted once-popular attractions like nightclubs into tournament ready venues. Eager sports market Las Vegas’ first foray into the esports venue occurred in 2017 with the Millennial Esports Arena’s opening, a 500-person capacity arena replacing a nightclub.[46] [47] In 2018, another Vegas venue opened: the “Esports Arena” a 30,000 square foot facility with a 1,500-person capacity that replaced a Luxor nightclub.[48] The Esports Arena touts a production ready setup that includes a broadcast center, massive LED video wall, and a custom tailored, video game inspired cocktail bar and menu.[49] By catering to the needs of tournament organizers, diehard fans, and even just the casual observer, Luxor intends to use the fusion of Vegas’s unique charm (cocktail bars and restaurants) with gamers’ expectations to make the Esports Arena the ultimate destination in esports.[50]

Within its first year, the Esports Arena made strides to make its name mainstay in esports venues. The arena had a successful inaugural year and was named Venue of the Year at the 2018 Esports Business Summit which it can credit its events staging for industry leaders like Tyler “Ninja” Blevins, Riot Games, and Capcom.[51] At the grassroots level, the venue was used as the location for the Fighting Game Community’s (FGC) beloved “Wednesday Night Fights” (a weekly fighting game competition with a Vegas-like buy-in ) and later, the Capcom Cup – a prestigious publisher sponsored Street Fighter tournament with a purse of $250,000.[52] [53] Though Capcom Cup was not without issues, the Esports Arena’s ability to host multi-day high-level tournaments were still acknowledged.[54] As a result of these efforts, HyperX, an endemic esports peripherals and components brand, has secured excusive naming rights to the Esports Arena in hopes of growing brand engagement. On the other side, Las Vegas and Luxor hope that esports can offer a new avenue for betting services to attract nontraditional gamblers to the city.[55]

Within its first year, the Esports Arena made strides to make its name mainstay in esports venues. The arena had a successful inaugural year and was named Venue of the Year at the 2018 Esports Business Summit which it can credit its events staging for industry leaders like Tyler “Ninja” Blevins, Riot Games, and Capcom.[51] At the grassroots level, the venue was used as the location for the Fighting Game Community’s (FGC) beloved “Wednesday Night Fights” (a weekly fighting game competition with a Vegas-like buy-in ) and later, the Capcom Cup – a prestigious publisher sponsored Street Fighter tournament with a purse of $250,000.[52] [53] Though Capcom Cup was not without issues, the Esports Arena’s ability to host multi-day high-level tournaments were still acknowledged.[54] As a result of these efforts, HyperX, an endemic esports peripherals and components brand, has secured excusive naming rights to the Esports Arena in hopes of growing brand engagement. On the other side, Las Vegas and Luxor hope that esports can offer a new avenue for betting services to attract nontraditional gamblers to the city.[55]

Dedicated Stadiums

Not to be outdone by Sin City, Arlington, Texas, a city just outside of Dallas (a legendary hub of American Counter-Strike), revealed plans in 2018 for a $10 million esports stadium to establish itself as a hub for gaming in the American South.[56] Arlington’s 100,000 square foot stadium of technological innovation is intended to cement the city is an opening gambit to ‘seize’ the position of the esports leader in the United States as well as associate Arlington as a staple in the esports industry.[57] Arlington’s location in the middle of the Dallas-Fort Worth Area positions itself in a premier location surrounded by traditional, celebrated sports brands.[58] Arlington’s sizeable and expensive arena aims to pull investment and attention away from the current American esports market leader, California and Las Vegas, the upstart in the desert.[59]

Esports Stadium Arlington’s location among some of the most legendary sports marquees is its greatest advantage against its competitors; its neighbors include AT&T Stadium, home to the Dallas Cowboys and Globe Life Field, the new home of the Texas Rangers.[60] Prior to the completion of the stadium, the Cowboys purchased Complexity Gaming, a beloved North American esports team with plans to physically integrate the organization into their office headquarters.[61]

Esports Stadium Arlington’s location among some of the most legendary sports marquees is its greatest advantage against its competitors; its neighbors include AT&T Stadium, home to the Dallas Cowboys and Globe Life Field, the new home of the Texas Rangers.[60] Prior to the completion of the stadium, the Cowboys purchased Complexity Gaming, a beloved North American esports team with plans to physically integrate the organization into their office headquarters.[61]

The stadium’s first event was the Esports Championship Series’ (ECS) Season 6 finals. ECS is considered by most Counter-Strike viewers as one of the most premier professional circuits in the scene as Esports Stadium Arlington delivered an experience to match the hype: the finals in Arlington sold out to the to tune of 2,500 tickets with hundreds of thousands watching the livestream online.[62]

The stadium’s first event was the Esports Championship Series’ (ECS) Season 6 finals. ECS is considered by most Counter-Strike viewers as one of the most premier professional circuits in the scene as Esports Stadium Arlington delivered an experience to match the hype: the finals in Arlington sold out to the to tune of 2,500 tickets with hundreds of thousands watching the livestream online.[62]

To remain relevant, Esports Stadium Arlington must not only remember where they are located, but also remind gamers that the city of Dallas has legendary roots in North American esports and the stadium is built to serve a mainstay in the city’s legacy.

Virtual Arenas

Virtual Arenas

Much like physical venues, esports titles’ virtual venues offer sponsorship opportunities. Publishers have used in-game items and playing environments to promote teams, brands, and their own games. Capcom, Street Fighter publisher, sells “Capcom Pro Tour” themed stages and items to contribute to the prize pool of their tournament, the Capcom Cup. In Dota 2, Valve has provided teams with a branded in-game banner that displays their various sponsors. Just recently, the naming rights for Madden’s in-game football stadium was awarded to Pizza Hut.[63] Pizza Hut’s sponsorship is tied to its existing partnership with the NFL, who is collaborating with Madden Publisher EA Sports for their esports league, the Madden 20 Championship Series.[64]

For games where visual modification of the playing area is not detrimental to gameplay, in-game advertisements create branding value by featuring tournament and team sponsors for the duration of the competition alongside commercial breaks.

Professional Sports Investments

Traditional sports have recognized millennials’ changing entertainment preferences. In 2016, 76% of esports enthusiasts state that the viewing hours formerly dedicated to traditional sports are now used on esports.[65] To recover this lost interest, traditional sports franchises have injected much needed investment into the esports space.

NBA teams and owners have used esports to diversify their brands across multiple media platforms. The NBA 2K League, the first official sports league operated by a U.S. professional sports league, consists of twenty-two partnered NBA teams (and one China-based gaming organization) who compete against one another in Take-Two Interactive’s NBA 2K basketball video game franchise.[66]

Like their in-real-life counterparts, NBA 2K League teams consist of 5 individual players who train together and compete against other teams. To develop their skills, some franchises like Sacramento, Minnesota, and Cleveland have constructed dedicated training centers on-site at their respective NBA arenas.

In Sacramento, the Kings unveiled the “world’s first dedicated esports training facility and content studio inside [a] pro sports venue.”[67] King’s Guard (the Sacremento Kings’ gaming team name) players have the same access to care, treatment, and dining as the NBA players. Using the Golden 1 Center’s technological capabilities, the facility boasts a full-service studio which features a green screen room, 4K cameras, and the ability to connect to the stadium’s broadcast center – a world’s first.[68] The Kings call the facility a ‘venue within a venue’: located inside the Golden 1 Center, the facility, in addition to being a dedicated location for the King’s Guard and other Kings-affiliated gaming teams to stream and practice, has the ability to expand into the rest of the Golden 1 Center to accommodate audiences in theatre-style seating.[69] Most importantly, the facility allows the Kings to increase millennials and gen z’s engagement with their various brands and sponsors.

Last year, the Minnesota Timberwolves unveiled plans for the T-Wolves Gaming training center located inside Mayo Clinic Square.[70] Not to be outdone by the competition, Minnesota claims the training center will be the most state-of-the-art and best-in-class facility in the NBA 2K League. Replacing the Experience Center on the second floor of the building, the center closely mirrors the NBA 2K League studio design in Long Island, where the teams compete. The space is divided into two sections, a gaming space and office space – separating areas where players may focus on match preparation and areas that are available for events. The Timberwolves aim to increase brand awareness for the Courts campus at Mayo Clinic Square by placing this training center inside a prominent location that garners high daily exposure.

On November 21, 2019, Cleveland Cavaliers NBA 2K League franchise, Cavs Legion GC unveiled a 2,700 square foot esports center, the Legion Lair Lit by TCP. [71] The facility, which rivals other NBA 2K League facilities’ capabilities, features its own state-of-the-art technology and full-broadcast capabilities: twenty-six gaming stations with accompanying top-of-the-line peripherals, greenscreens, two-tier competitive seating for two six person teams, a video wall, sound-proof streamer pods, and a full content creation studio.

In its original plans, the gaming club set out to construct a facility that could accommodate the team, the local community, and offer educational opportunities. Through its local partnerships with TCP, the City of Cleveland, and Kent State, the team has tried meet these goals. TCP, who currently holds the facility’s naming rights, is a Cleveland-based lighting manufacturer who agreed to produce a smart lighting system that creates color schemes and reduces eye strain. As part of its efforts to draw local attention from local youth and schools, the team announced a partnership with the City of Cleveland to launch a city-based recreational esports club – the first of its kind.

Sacramento and Cleveland’s early investment in NBA 2K training centers reflects the proactiveness of smaller basketball markets. These franchises understand to compete with teams located in more populous markets with larger fanbases, increasing engagement from their existing fanbases and directing interest towards the brand is paramount. An NBA 2K franchise presents a marketing opportunity within established markets to drive continued interest to their brands.

The relationship between the NBA and esports does not end at 2K. NBA team owners have been privy to the possibilities of esports. In 2016, Milwaukee Bucks co-owner Wesley Edens purchased a sport in the LCS for around $1.8 million and formed FlyQuest.[72] One year later, the LCS franchise sports shifted from a regulation system to a permanent 10 team league. After committing $10 million to the league, Eden’s FlyQuest was one of the teams selected by Riot.[73] In 2017, Cavaliers owner Dan Gilbert made a multimillion-dollar investment in 100 Thieves, a clothing line and esports organization founded by former Call of Duty pro player Matthew “Nadeshot” Haag.[74] In 2019, 100 Thieves, which also has investors the likes of Drake, Scooter Braun, and Marc Benioff, is valued at $125 million dollars.[75] Sacramento Kings co-owners, Andy Miller and Mark Mastrov founded NRG Esports (NRG), a standalone professional esports organization. NRG’s investors include Alex Rodriguez, Shaquille O’Neal, and Jennifer Lopez.[76] Currently NRG competes in nine different esports, including the 2019 Overwatch League Champions, the San Francisco Shock.

Collegiate Sports Partnerships

Pairing education and video games, Universities have used official esports programs to reach a massive existing player base of university students.[77] Approximately 35 percent of League of Legends’ North American player base are full time students, 47 percent of whom do not participate in traditional school activities. Esports programs not only give these underserved students an opportunity to engage with campus communities, universities can attract collegiate-level players with academic interests in STEM. Since Robert Morris University created the first scholarship-sponsored League team in 2014, around 125 collegiate programs have been registered with the National Association of Collegiate Esports.[78] As the number of schools offering esports programs and scholarships continues to rise, so does the willingness to fund collegiate esports. In 2016, UC Irvine partnered with PC building company iBUYPOWER to construct the first public college esports arena in the US for its decorated program.[79] The 3,500-square-foot arena contains 80 PCs preloaded with esports title, a broadcasting studio, and viewing screens.[80]Aside from its use as a training facility for its varsity teams, the arena serves as an inclusive gathering space for the gaming community, and the school offers student staff roles and volunteer opportunities in coaching, analysis, streaming, and production areas.[81] More schools continue to recognize that investing in esports facilities also means investing in the interests and hobbies of its technology-interested students.

Of the schools that have invested in collegiate esports programs, Midwestern universities gained notoriety for their early adoption, investment, and success.[82] In St. Louis, Missouri, Maryville University boasts three League of Legends championships, a top four nationally-ranked Overwatch team, and the number 2 spot on ESPN’s 2019 college esports rankings.[83] Maryville’s staff consists of esports industry veterans who have overseen some of the professional scene’s most prominent teams and organizations.[84]

Kent State University, who has had an esport program since 2018, announced a partnership with Cavs Legion GC in September 2019 as part of an effort of increasing awareness for the university club and growing the local gaming community in the region.[85] In the Legion’s new facility, Kent State has exclusively branded two streaming pods to be used for content creation and broadcasting. In return, Kent State Esports will have access to the facility for team practices, event hosting, and educational programs.

In Milwaukee, Wisconsin, Marquette University was the first major conference Division I athletics program to announce the addition of a varsity esports program.[86] Though Marquette has had an esports club team since 2015, the push into collegiate athletics allows the team to join the BIG EAST Conference as well as host official tryouts, hire a coach, and have regular practices. Academically, Marquette hopes the team will have a productive partnership with its computer science department, increase student recruitment, and give an outlet to develop leadership and teamwork abilities in students who may otherwise not have been engaged in these activities. To develop their program, Marquette has announced plans to work with corporate partners and donors to build an esports arena so that the varsity team has a practice space as well as a production station open to student groups. Like other schools, Marquette Esports is a way to merge out-of-classroom interests with hands-on learning opportunities.

IV. Learning from Example (the concept)

There is still no clear “winner” in the race for esports’ flagship stadium. In fact, the success of esports stadium is dependent on an upsettingly abstract quality: authenticity. Before an esport stadium is even visually conceptualized, venue developers need to consult not just professional gamers, team owners, tournament organizers, broadcasters, but the fans as well. The inclusion of technology like LED screen walls and augmented reality in stage tournaments were implemented to appease attendants both in person and online, but venue developers need to be wary of interfering with competitive integrity and a wholesome viewership experience. The appreciation of these technologies is at the mercy of a temperamental fan base: an LED screen wall may be aesthetically awe-inducing to viewers but will eventually lose its novelty if the screen wall too invasively affects the viewership experience. For the sake of comparison, measuring the newly finished Esports Stadium Arlington against the old guard of the LANXESS arena would yield a resounding victory for the Texas venue – on paper. The LANXESS is not a purposefully built arena for esports – nor does it claim to be, but despite that, in the past three years it has sold out and is held in the highest of esteem as a landmark destination for Counter-Strike because the arena possesses an immeasurable quality of mystique that adds to the lore of a tournament. Gamers are skeptical of gimmicks: simply touting the latest oversized LED screen to scrounge up attendance without a practical, competitive purpose will only be met with reservation; however, convincingly offering a setting where a viewer can be immersed in legend will attract gamers worldwide. Immediately considering localized stadiums for newly franchised teams in a fresh league is an irresponsible practice that fails to consider the importance of development the sense of authenticity that becomes exclusive to an individual esports title.

It is undeniable that esports’ final product requires the implementation of the formula that has yielded traditional sports stadiums’ success. Naming rights, concessions, advertising, sponsorship, and technological innovation drive investment and instill confidence in developing any venue, but esports, perhaps to a fault, requires a level of respect for the preexisting “culture” that needs to be met before skepticism can fade. Even though it may seem like a final boss, authenticity is just the gatekeeper.

Patrick P. Hankins is a third-year law student at Marquette University Law School and a 2020 Sports Law Certificate Candidate. He is a Thomas More Scholarship recipient and Clifford Meldman scholar as well as a member of the 2019-20 Marquette Sports Law Review. While at Marquette, Hankins has held roles as a legal intern for Martin J. Greenberg and esports attorney Roger Quiles. Prior to his time at Marquette, Hankins attended the University of Colorado at Boulder and earned his bachelor’s degree in English Literature. There, his coursework included economics, digital media, and a project related to esports gambling. In addition to his academics, Hankins was a member of CU’s cycling club. Next spring, Hankins will graduate with a J.D. from Marquette University Law School.

[1] Andrew Lynch, Tracing the 70-year history of video games becoming eSports, FOX SPORTS, (May 6, 2016), https://www.foxsports.com/buzzer/story/esports-explainer-league-of-legends-heroes-of-the-storm-hearthstone-cs-go-dreamhack-050616.

[2] Id.

[3] Id.

[4] Kevin Kelly, The First Online Sports Game, WIRED, (June 1, 1933, 12:00 PM), https://www.wired.com/1993/06/netrek/.

[5] Dave Consolazio, The History of Esports, HOTSPAWN, (Oct. 7, 2018), https://www.hotspawn.com/the-history-of-esports/.

[6] Consolazio

[7] Id.

[8] CYBERATHLETE PROFESSIONAL LEAGUE, https://web.archive.org/web/20131105065035/http://thecpl.com/the-cpl-heritage/ (last captured Nov. 5, 2013).

[9] John Gaudiosi, CPL Founder Angel Munoz Explains Why He Left Esports And Launched Mass Luminosity, FORBES, (Apr. 9, 2013, 11:02 AM), https://www.forbes.com/sites/johngaudiosi/2013/04/09/cpl-founder-angel-munoz-explains-why-he-left-esports-and-launched-mass-luminosity/#60b84857648e.

[10] Paul Mozur, For South Korea, E-Sports Is National Pastime, THE NEW YORK TIMES, (Oct. 19, 2014), https://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/20/technology/league-of-legends-south-korea-epicenter-esports.html?_r=0.

[11] Id.

[12] Ben Popper, Field of streams: how Twitch made video games a spectator sport, THE VERGE, (Sep. 30, 2013, 9:00 AM), https://www.theverge.com/2013/9/30/4719766/twitch-raises-20-million-esports-market-booming.

[13] Christopher D. Merwin, Masaru Sugiyama, Piyush Mubayi, Toshiya Hari, Heath P. Terry, Alexander Duval, The World of Games eSports: From Wild West to Mainstream, GOLDMAN SACHS, (Oct. 12, 2018, 12:39 PM), https://www.goldmansachs.com/insights/pages/infographics/e-sports/report.pdf.

[14] Christina Cough, eSports market – Statistic & Facts, STATISTA, (Mar. 7, 2019), https://www.statista.com/topics/3121/esports-market/.

[15] Id.

[16] Merwin at 13.

[17] Id at 14.

[18] The Evolution of Esports Venues, ROSSETTI, (Jan. 9, 2018), http://www.rossetti.com/about/news/posts/evolution-esports-venues.

[19] Bryce Blum, Power Dynamics in Esports – the Role of the Publisher, ESPN, (May 18, 2016), http://www.espn.com/esports/story/_/id/15577117/power-dynamics-esports-role-publisher.

[20] Id.

[21] Tomi Kovanen, lurppis: Only Valve can fix CS:GO’s scheduling problems, ESPN, (July 18, 2017), http://www.espn.com/esports/story/_/id/20096529/counter-strike-global-offensive-pgl-major-krakow-scheduling-issues.

[22] Id.

[23] VALVE CORPORATION, http://blog.counter-strike.net/index.php/2016/01/13442/

[24] ESPORTS INTEGRITY COALITION, https://www.esportsintegrity.com/2017/07/esic-statement-on-appropriate-sanction-for-cheating-in-esports/

[25] VALVE CORPORATION, http://blog.counter-strike.net/index.php/csgo-major-selection-process-faq/

[26] Editorial, ESL One Cologne Celebrates 5th Year Anniversary at LANXESS Arena in 2019, (Nov. 26, 2018), https://www.esl-one.com/csgo/cologne-2019/2018/11/esl-one-cologne-celebrates-5th-year-anniversary-at-lanxess-arena-in-2019/.

[27] Ethan Gach, Valve Makes ‘Exclusive’ Streaming Deals like Facebook’s Incredibly Confusing, KOTAKU, (Jan. 25, 2018, 3:20 PM), https://kotaku.com/valve-makes-exclusive-streaming-deals-like-facebooks-in-1822424636.

[28] BLUM, supra note 11.

[29] Id.

[30] Id.

[31] Matt Porter, Riot is Changing the Game with the ‘League of Legends’ European Championship, FANDOM, (Nov. 20, 2018), https://www.fandom.com/articles/league-of-legends-european-championship-2019.

[32] Imad Khan, Riot Released details on NA LCS franchising with $10M flat-fee buy-in, ESPN, (Jun. 1, 2017), http://www.espn.com/esports/story/_/id/19511222/riot-releases-details-na-lcs-franchising-10m-flat-fee-buy-in.

[33] Id.

[34] Bryce Blum, Franchising in esports mean esports are here to stay, ESPN, (Jun. 1, 2017), http://www.espn.com/esports/story/_/id/19514784/franchising-esports-means-esports-here-stay.

[35] Bear Schmiedicker and Dave Stewart, Home of the NA LCS, LEAGUE OF LEGENDS CHAMPIONSHIP SERIES LLC, (Mar. 6, 2017), https://www.lolesports.com/en_US/articles/arena-home-of-the-na-lcs.

[36] Jersey Mike’s Subs joins as the latest NA LCS sponsor, LEAGUE OF LEGENDS CHAMPIONSHIP SERIES LLC, (Jun. 15, 2018), https://www.lolesports.com/en_US/articles/jersey-mikes-subs-joins-latest-na-lcs-sponsor.

[37] State Farm and NA LCS partner up in 2018, LEAGUE OF LEGENDS CHAMPIONSHIP SERIES LLC, (Jan. 20, 2018), https://www.lolesports.com/en_US/articles/state-farm-and-na-lcs-partner-2018.

[38] Darren Heitner, Full 12 Franchises Announced For Initial Overwatch League Season, FORBES, (Sep. 20, 2017, 9:00 AM), https://www.forbes.com/sites/darrenheitner/2017/09/20/full-12-franchises-announced-for-initial-overwatch-league-season/#12d0127a2c65.

[39] Id.

[40] Arash Markazi, No one mold for esports venues as arenas continue to grow, ESPN, (Dec. 23, 2018), http://www.espn.com/esports/story/_/id/25602388/no-one-mold-esports-venues-arenas-continue-grow.

[41] Tyler Erzberger, Blizzard Entertainment unveils Blizzard Arena, ESPN, (Oct. 7, 2017), http://www.espn.com/esports/story/_/id/20946685/blizzard-entertainment-unveils-blizzard-arena.

[42] Kevin Webb, Eight teams paid more than $30 million each to join the Overwatch League – here’s everything you need to known before the new season starts, BUSINESS INSIDER, (Dec., 29, 2018), https://www.businessinsider.com/overwatch-league-season-2-2018-9.

[43] Brian Bencomo, L.A. Valiant of Overwatch League introduced to L.A. Kings fans, ESPN, (Jan. 11, 2019), http://www.espn.com/esports/story/_/page/overwatchleaguevaliantkings/los-angeles-valiant-overwatch-league-introduced-los-angeles-kings-fans?platform=amp.

[44] Jacob Wolf, Overwatch League aims to get teams to their home cities by 2020, sources said, ESPN, (June 6, 2018), http://www.espn.com/esports/story/_/id/23715508/overwatch-league-aims-get-teams-their-home-cities-2020-sources-say.

[45] Irwin Kishner & Erica L. Markowitz, eSports Investments: Virtual Games Require Real Due Diligence, MONDAQ, July 6, 2017.

[46] Steve Roberson, Grand Opening of First Ever Permanent Las Vegas Esports Arena, ESPORTS IN LAS VEGAS (Feb. 13, 2017), https://www.esportsinlasvegas.com/grand-opening-first-las-vegas-esports-arena/.

[47] Jacob Wolf, Millennial Esports announces Friday opening of Las Vegas esports arena, ESPN (Feb. 25, 2017), http://www.espn.com/esports/story/_/id/18766149/millennial-esports-esports-announces-friday-opening-las-vegas-esports-arena.

[48] Mallory Locklear, The Las Vegas strip’s first eSports arena opens in March, ENGADGET (Jan. 12, 2018), https://www.engadget.com/2018/01/12/las-vegas-strip-esports-arena-opens-march/.

[49] Markazi

[50] Id.

[51] BUSINESS WIRE, (Nov. 16, 2018), https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20181116005084/en/HyperX-Allied-Esports-Announce-HyperX-Esports-Arena.

[52] Markazi

[53] Michael Martin, Capcom Cup 2018 Heads to Esports Arena Las Vegas, CAPCOM, U.S.A., INC., (Sep. 14, 2018), https://capcomprotour.com/capcom-cup-2018-heads-esports-arena-las-vegas/.

[54] Ian Walker, Street Fighter V Competitors Carry an Otherwise Messy Capcom Cup, KOTAKU UK, (Dec. 18, 2018), http://www.kotaku.co.uk/2018/12/17/street-fighter-v-competitors-carry-an-otherwise-messy-capcom-cup.

[55] https://thenextweb.com/gaming/2017/03/01/las-vegas-bets-big-on-new-esports-arena-attracting-millennials/

[56] Virginia Glaze, How Texas’s New Esports Initiative Is Shaping Gaming in the Lone Star State, RED BULL (April 16, 2018), https://www.redbull.com/us-en/texas-arlington-esports-arena-community.

[57] Id.

[58] Id.

[59] Id.

[60] Markazi

[61] Jason Lake, Honest, transparent thoughts on a big day, FACEBOOK (Nov. 6, 2017), https://www.facebook.com/notes/jason-lake/honest-transparent-thoughts-on-a-big-day/723233421214617/.

[62] Jonathon Oudthone, Esports Sodium Arlington Opens With Sold-Out Crowd At Inaugural Event, CBS DFW (Nov. 24, 2018), https://dfw.cbslocal.com/2018/11/24/esports-stadium-arlington-opens-sold-out-crowd/.

[63] Steven Impey, NFL awards Pizza Hut first virtual stadium naming rights deal in Madden tie-up, SPORTS PRO (July 30, 2019), http://www.sportspromedia.com/news/nfl-pizza-hut-virtual-stadium-naming-rights-madden-esports.

[64] Id.

[65] Pieter van den Heuvel, US Male Millennials View as Much Esports as They Do Baseball or Hockey, NEWZOO, (Oct. 12, 2016), https://newzoo.com/insights/articles/why-brands-and-esports-are-entering-esports/.

[66] https://2kleague.nba.com/league-info/

[67] https://www.nba.com/kings/pressrelease-1272017

[68] Id.

[69] Id.

[70] https://twolvesgaming.nba.com/news/t-wolves-gaming-unveils-plans-for-new-training-center/

[71] https://cavslegion.nba.com/legionlairtcp/

[72] https://www.espn.com/esports/story/_/id/18239215/league-legends-sources-bucks-co-owner-wesley-edens-buys-esports-25-million

[73] https://www.bizjournals.com/milwaukee/news/2017/11/24/wes-edens-e-sports-team-gains-permanent-status-in.html

[74] https://www.gamesindustry.biz/articles/2017-11-21-dan-gilbert-makes-multimillion-investment-in-100-thieves

[75] https://nypost.com/2019/07/16/drakes-esports-team-100-thieves-raises-35-million/

[76] https://www.nrg.gg/about

[77] http://www.bigeast.com/news/2019/1/24/general-marquette-is-first-major-conference-ncaa-division-i-institution-to-add-a-varsity-esports-program-in-athletics.aspx

[78] Sean Morrison, List of varsity esports programs spans North America, ESPN, (Mar. 15, 2018), https://www.espn.com/esports/story/_/id/21152905/college-esports-list-varsity-esports-programs-north-america.

[79] Jessica Conditt, UC Irvine debuts the first public college esports arena in the US, ENGADGET, (Sep. 14, 2016), https://www.engadget.com/2016/09/14/esports-arena-college-uc-irvine-leage-of-legends/.

[80] Id.

[81] Id.

[82] https://www.espn.com/college-sports/story/_/id/21130531/midwest-emerges-home-college-esports

[83] https://www.maryville.edu/studentlife/esports-clubs/

[84] Id.

[85] https://cavslegion.nba.com/news/legion-partners-with-kent-state/

[86] https://gomarquette.com/news/2019/1/22/marquette-is-first-major-division-i-institution-to-add-varsity-esports.aspx