By Martin J. Greenberg and Michael R. Gavin

When a National Football League (NFL) franchise desires to obtain stadium financing to either construct a new stadium or renovate a current stadium, the franchise typically raises funds through a public-private partnership.[1] Public funding is classified as “funds, property transfers, or tax abatements that come at the expense of taxpayers.”[2] State and local governments provide public funding through issuing and selling bonds.[3] State and local governments support those bonds through the imposition of sales taxes; ticket admission taxes; and lodging, car rental, and sin taxes.[4] Private funding is money typically generated through means other than public taxation.[5] Examples of private funding include invested capital, personal seat licenses (PSLs), facility revenues, secured loans, and the NFL’s G-4 program to name a few.[6]

For NFL stadiums built since 1997, on average, fifty-six percent of the money raised to finance an NFL stadium comes from public funding, with the remaining forty-four percent from private funding.[7] The average stadium construction cost since 1997 is $525.4 million, and all of the stadiums except for MetLife Stadium (New York Giants and New York Jets) have used some form of public funding.[8] Recently built NFL stadiums are extraordinarily costly. Here is a listing of some of the most recent NFL stadiums and the approximate cost of construction:

| NFL Franchise | Stadium | Year Opened | Cost |

| New York Jets & New York Giants | MetLife Stadium | 2009 | $1.6 billion[9] |

| Dallas Cowboys | AT&T Stadium | 2009 | $1.3 billion[10] |

| San Francisco 49ers | Levi’s Stadium | 2014 | $1.2 billion[11] |

| Minnesota Vikings | U.S. Bank Stadium | 2016 (projected) | $1.08 billion[12] |

| Atlanta Falcons | Mercedes-Benz Stadium | 2017 (projected) | $1.4 billion[13] |

| Los Angeles Rams (plus one more team) | Inglewood Stadium | 2019 (projected) | $3.0 billion[14] |

The NFL’s stadium financing participation began in 1999 with the birth of the G-3 program (G-3).[15] The purpose of G-3 was to enable the NFL to offer assistance to teams that desired to build new stadiums.[16] In order to receive G-3 funding, the following requirements needed to be met:

- The stadium project must be public-private funded.[17]

- The NFL would match up to $150 million of a team’s private ownership contributions for a new stadium, in which the contributions came from new facility revenue streams.[18] The contributions came from revenues applicable to PSLs, stadium naming rights, and luxury loges.[19]

- If a team fails to contribute enough towards their stadium project, funds will be taken from the NFL’s $18 billion TV contract.[20]

- The NFL will be repaid by the visiting team’s share of luxury box and club seat revenues, but can be exempted if they are used for directly financing the non-G-3 stadium’s construction.[21]

G-3 experienced initial success, but as time went on, the money supply for G-3 depleted and the NFL was faced with the task of changing the program.[22]

John Vrooman in his chapter entitled “The Economic Structure of the NFL,” best described G-3 as follows:

The private funding of Joe Robbie Stadium created a revenue-sharing problem for the rest of the League that was solved when the other owners agreed to waive the visiting team share (VTS) of luxury seats if the fees were used in the construction of the stadium (the premium seat waiver). The VTS waiver was later extended to personal seat licenses (PSLs) used for venue construction after the Carolina Panthers sold $122 million in PSLs for a 76.3% private funding of Bank of America (Ericsson) Stadium in 1996.

Perhaps the most important factor in the second half of the venue revolution was the League’s extension of the premium waiver into the creation of a full blown credit facility for venue finance. After the New England Patriots aborted relocation to Hartford in 1999, the NFL began a G-3 loan program (NFL Constitution and Bylaws, 1999 Resolution G-3) where stadium loans were to be repaid from 34% VTS of club seat premiums. The League loaned up to 50% of private costs (maximum $150 million) for teams in six largest TV markets, and up to 34% (maximum $100 million) for clubs in smaller markets.

Since the NFL’s $10.8 billion venue revolution began public coffers have been hit for about one-half the cost. The 12 stadiums built under the $1.1 billion G-3 program averaged 59% private share and one-fourth of the private share was from G-3 loans. The 13 stadiums built in relocation/extortion period before G-3 averaged only 26.6% private funding and 60% of the private share came from PSLs. The good news is that the G-3 program was shifting the financing burden to the NFL teams rather than the general tax-paying public, but the bad news was that the internal private burden was being shifted to smaller markets through the premium waiver and to players through stadium cost exemptions from the salary cap revenue base.[23]

The following teams received funding under G-3:

| NFL Franchise | Amount Received From G-3 Program[24] |

| Denver Broncos | $48 million |

| New England Patriots | $141 million |

| Detroit Lions | $100 million |

| Seattle Seahawks | $63 million |

| Philadelphia Eagles | $125 million |

| Chicago Bears | $100 million |

| Green Bay Packers | $13 million |

| Arizona Cardinals | $42 million |

| Indianapolis Colts | $33 million |

| Dallas Cowboys | $76 million |

| Kansas City Chiefs | $43 million |

| New York Giants & Jets | $300 million |

During the 2011 NFL offseason, the NFL and the National Football League Players Association (NFLPA) negotiated a new collective bargaining agreement (CBA) because the previous CBA expired on March 11, 2011, and a lockout officially began the following day.[25] The CBA negotiations were rather unpleasant between the parties until the NFLPA unanimously approved a new deal on July 25, 2011, thus ending the four and one-half month lockout.[26] One of the most significant provisions of the new CBA was the recreation of G-3, called the G-4 program (G-4).[27] G-4 is mentioned under Article 12, Section 4 of the CBA entitled “Stadium Credit.”[28]

In 2011, the NFL adopted Resolution G-4, which states as follows:

In 2011, the NFL adopted Resolution G-4, which states as follows:

Whereas, the stadium construction support program established by 1999 Resolution G-3, as extended by 2003 Resolution JC-1 (the “G-3 Program”), contributed to the completion of 12 stadium projects benefitting 13 clubs; and

Whereas, the G-3 Program reached its pre-established funding capacity in 2006, and since such time no new major stadium projects have been approved; and

Whereas, a new stadium construction support program (the “G-4 Program”) would assist in building new stadiums that would provide many benefits to the League and clubs, including potentially (a) supporting franchise stability and national television contracts, (b) enhancing the in-stadium fan experience, and [(c)] allowing the League and clubs to remain competitive with other sports and entertainment offerings; and

Whereas, the G-4 Program should take into account certain developments since the institution of the G-4 Program, such as (a) the substantial increase in private contributions to stadium construction costs, (b) the League’s institution of certain stadium financing guidelines, and [(c)] stadium credits available under the League’s new collective bargaining agreement with the NFLPA; and

Whereas, any amounts made available to a club or its related stadium affiliate under the G-4 Program should require separate member club approval on a case-by-case basis;

Be it Resolved:

- That for any stadium construction project (new stadium or stadium renovation the costs of which will exceed $50 million) involving a private investment for which an affected club or its affiliated stadium entity (“Developing Club”) makes a binding commitment, either NFL Ventures, an affiliate of NFL Ventures or another entity designated by the Finance Committee (the “League-Level Lender”) shall provide funding (“League-Level Funding”) of up to $200 million in the aggregate to the Developing Club to support such project based on the amount that the Developing Club has committed or that will be applied to such project (either through the issuance of equity or the application of PSL proceeds or, except as otherwise provided below in respect of the Second Tranche, through debt incurred by the applicable entity) as a private contribution (the “Private Contribution”) as follows:

- For up to $200 million of project costs for a new stadium and up to $250 million of project costs for a stadium renovation, the League-Level Lender will advance a loan equal to the lesser of the amount of the Private Contribution to such costs and $100 million (i.e., stadium renovations shall be subject to a $50 million deductible to be funded by a Private Contribution) (the “First Tranche”), with such loan to be repaid through waived club seat premium VTS and “Incremental Gate VTS” (defined below) during the first 15 seasons of operations in the new stadium and to otherwise include such terms, including with respect to maturity, interest, repayment and subordination, as the League-Level Lender may determine, provided that the controlling owner of the club will be required to guarantee and pay on a current basis any shortfalls in scheduled repayments due to club seat premium VTS and Incremental Gate VTS falling below the amounts necessary for such repayments;

- If there has been a Private Contribution of $100 million ($150 million in the case of a stadium renovation) towards the costs referenced in subsection (a) above, then for project costs between $200 million and $350 million for a new stadium, and for project costs between $250 million and $400 million for a stadium renovation, the League-Level Lender shall provide, in a manner determined by the Finance Committee on a case-by-case basis, an amount equal to 50% of the Private Contribution towards such costs (i.e., the League-Level Lender will provide up to $50 million of such costs) (the “Second Tranche”), provided that for purposes of such funding, only Private Contributions in the form of proceeds from the issuance of equity or the sale of PSLs shall be counted; and

- If there has been a Private Contribution of $200 million ($250 million in the case of a stadium renovation) towards the costs referenced in subsections (a) and (b) above, then the League-Level Lender will advance a loan to the Developing Club of up to $50 million to cover the project costs between $350 million and $400 million for a new stadium, and for the project costs between $400 million and $450 million for a stadium renovation (the “Third Tranche”), with such loan to be made on such terms, including with respect to maturity, interest rate, repayment and subordination, as the League-Level Lender may determine, provided that any such loan shall be guaranteed by the controlling owner of the club.For purposes of this resolution, Incremental Gate VTS means the amount by which gate VTS in the new or renovated stadium exceeds the greater of (i) the average of the final three years of gate VTS in the old or pre-renovated stadium and (ii) the gate VTS in the final year of operations in the old or pre-renovated stadium, in each case with the gate VTS in the old or pre-renovated stadium being increased on a cumulative annual basis at a percentage for any year equal to the League-wide year-over-year percentage increase in gate VTS for the then current season compared to the prior year, excluding for purposes of such percentage calculation gate VTS from new or substantially renovated stadiums that are not operational for the full two seasons. Notwithstanding the foregoing, in the event that the final year in the old or pre-renovated stadium is 2010, then for 2011 only, the increase in the actual gate VTS shall be deemed to be 2%.

- That any stadium renovations less than $50 million and more than $10 million shall be eligible for a club seat premium waiver, debt ceiling waiver and/or PSL waiver (in each case subject to separate approval from the membership).

- That League-Level Funding to a project will, unless the Finance Committee otherwise determines on a case-by-case basis, be made in conjunction with other funding sources on a pro rata basis (e.g., unless the Finance Committee otherwise determines, if the project is estimated to cost $1 billion and the League-Level Funding will total $200 million, then for every $4 of funding from other sources put into the project, $1 of League-Level Funding will be put into the project).

- That League-Level Funding in support of a stadium construction project shall be subject to membership approval on a case-by-case basis following an evaluation of the criteria specified on Attachment A to this Resolution; provided, that no League-Level Funding shall be made to any stadium project if the impact to the member clubs as a result of the Second Tranche League-Level Funding for all projects under the G-4 Program would exceed $1 million per club per year for a 25-year period ending on March 31, 2037 (such projection to be determined by the Commissioner, in his sole discretion); and provided further, that the Stadium and Finance Committees shall not recommend any League-Level Funding for membership approval unless:

- The club seeking such support shall have provided the relevant League committees with such information as they shall have requested in respect of the project, including without limitation detailed information regarding sources and uses of funds, projections, project scope, compliance with League policies, etc.;

- The controlling owner of the club seeking such support shall have provided guarantees of First Tranche and Third Tranche League-Level Funding (and other affiliated entities shall have provided any additional adjacency or other guarantees required by the Finance Committee on a case-by-case basis);

- The club shall be in compliance, to the Finance and Stadium Committees’ satisfaction, with the League’s then applicable stadium financing debt guidelines, including, to the extent the Finance Committee deems necessary or appropriate, that the club’s owners shall have committed to fund additional equity contributions to the extent necessary to maintain compliance with such guidelines;

- The stadium construction project must be a “public-private partnership”;

- The project must not involve any relocation of or change in an affected club’s “home territory” (as defined in the Constitution and Bylaws);

- No project proposal may be accepted from any club that, within the year prior to its submission of such proposal, had pending or had supported litigation against the League or any of its clubs or affiliated entities (other than in the context of a proceeding brought before the Commissioner under Article VIII of the Constitution and Bylaws); and

- Increases in the visiting team share generated by the new or renovated stadium must meet the standards set forth in the 1994 Club Seat Sharing Exemption Guidelines.

- That the Commissioner is authorized to make arrangements for the League-Level Lender to borrow from commercial or institutional lenders funds to make League-Level Funding available under the G-4 Program, with the funds to be repaid to such lenders over an appropriate time period (25 years after the inception of the G-4 Program, or such other period as may be determined by the Finance Committee), on such terms as the Commissioner may deem appropriate and as may be approved by the Finance Committee.

- That the League-Level Lender is authorized to withhold, or the member clubs shall otherwise pay, any amounts from time to time due and owing under the loans referenced in paragraph 5 above and which are not fully covered with respect to the clubs participating in the G-4 Program through application of the amounts referenced in paragraph 1 hereof.

- That if PSLs are sold (whether by the applicable club, its affiliated stadium entity, a municipal authority or otherwise) with respect to a particular stadium construction project, such PSLs shall be entirely dedicated to the project costs in respect of such project and shall be eligible for an exemption from sharing in accordance with current policies.

- That any club debt ceiling waiver associated with a stadium construction project (and separately approved by a membership vote) must expire in either (a) no more than 15 years, if such debt is amortized over such time mortgage-style or (b) no more than 25 years, provided that for a 25-year waiver, the Finance Committee shall in its discretion require “step-down” payments providing for amortization that is more rapid than mortgage-style amortization.

- That if a club (or its affiliated stadium entity) receives League-Level Funding under the G-4 Program and either such club or its affiliated stadium entity (or a controlling interest therein) is thereafter sold other than to a member of the controlling owner’s immediate family (as defined in the NFL Constitution and Bylaws) before the final maturity date of the League-Level Funding or the franchise is relocated from such club’s “home territory” before such final maturity date, then the selling or relocating party shall repay the League-Level Lender (in the case of a sale, from the sale proceeds at closing) an amount equal to the outstanding principal balance of the League-Level Funding.

- That definitions and policies with respect to what constitutes project costs and allowable annual consideration (e.g., rent) shall remain consistent with the definitions and policies under the G-3 Program, subject to such modifications, if any, as may be determined by the Finance Committee.

- That the membership delegates to either of the Finance and Stadium Committees the authorization to: (a) evaluate club projections for stadium projects (e.g., revenues, construction costs and operating expenses); (b) require adjacency or other guarantees; [(c)] authorize League-Level Lender staff to review and/or to engage third party experts (e.g., investment banks) to review club, affiliate entity and controlling owner financial statements and condition for purposes of evaluating the ability of such parties to meet their guarantee and other obligations under the G-4 Program, which reviews may occur both as part of the approval process for an applicable club’s stadium project and at any time thereafter as deemed appropriate by the Finance or Stadium Committees; (d) require owner equity funding obligations to maintain compliance with stadium debt financing guidelines; (e) establish rules relating to funding priority for teams that have previously received stadium construction support from the League-Level Lender or an affiliate; (f) approve step paydown requirements for 25-year debt waivers; (g) establish the identity of the League-Level Lender and the structure of Second Tranche League-Level Funding; (h) establish the timing for funding of League-Level Funding, if other than pro rata as referenced in paragraph 3; (i) determine definitions and policies with respect to what constitutes project costs and allowable annual consideration; and (j) approve the terms of any debt referenced in paragraph 5 herein, and the terms of transactional documentation implementing repayment obligations with respect to League-Level Funding.

- Notwithstanding the foregoing, the foregoing matters shall also be subject to any requisite approvals of the League-Level Lender, to the extent the League-Level Lender is not the League.[29]In a press conference with Commissioner Goodell, he aptly described G-4:There are several new wrinkles. We’ll be happy to give you the resolution. It’s several pages. I think it’s much improved over the prior G-3 program including additional money that will be available based on the private contribution to these projects. They’ve become more complex and more expensive in these markets and we had to adjust our policy to participate in these projects and support these projects both at the club level and league level. We’re the only league I’m aware of to contribute league money as well as local money to these projects. Again I think that’s why we have great facilities for our fans.[30]

G-4 in essence provides NFL franchises an additional avenue of obtaining debt financing through the NFL in order to undergo a stadium construction or renovation project.[31] G-4 is financed by one and one-half percent (1.5%) of the NFL’s annual revenue, which was approximately $11.2 billion in 2014.[32] Thus, G-4 funds available for 2015 would be $168 million. The following summarizes the guidelines regarding G-4 funding:

- Only public-private stadium projects are eligible for the G-4 loans;

- The NFL will determine the G-4 loan issuances on a case-by-case basis;

- The NFL will provide franchises up to $200 million for constructing a new stadium;

- If a franchise renovates their stadium, the NFL will provide up to $250 million;

- The G-4 financing will be repaid over a period of fifteen years derived from premium seating ticket revenue;

- The franchise receiving the G-4 loan funds must not relocate or change the franchise’s “home territory[;]”[33] and

- Only projects costing $400 million and with a private contribution from the team of at least $200 million will be eligible for the top loan level.[34]

From 2009-2013, the interest rate for both G-3 and G-4 was approximately two percent.[35] Under G-4, ten (potentially eleven) NFL franchises have received financial assistance. Those participating teams and the amounts they received under G-4 are as follows:

| NFL Franchise | Amount Received From G-4 (if available) |

| Atlanta Falcons | $200 million[36] |

| Carolina Panthers | $37.5 million[37] |

| Cleveland Browns | $62.5 million[38] |

| Green Bay Packers | $58 million[39] |

| Los Angeles Rams (plus second franchise) | $200 million (potentially $400 million)[40] |

| Miami Dolphins | $50 million[41] |

| Minnesota Vikings | $200 million[42] |

| Philadelphia Eagles | No financial information available |

| San Francisco 49ers | $200 million[43] |

| Washington Redskins | $27 million[44] |

Why are NFL teams using G-4? By constructing a new stadium or renovating an older one, teams hope for the opportunity to host Super Bowl Sunday.[45] G-4 is attractive to the teams because the NFL is a great financier, and the program thrives as a source of financing. According to Fitch Ratings, one of the three nationally recognized statistical rating organizations designated by the United States Securities and Exchange Commission, G-4, under NFL Ventures, LP, received an “A+” rating.[46] An “A+” Fitch rating is described as an “upper medium quality” bond.[47] Key drivers of the NFL’s rating for G-4 were strong underlying league economics and governance, long history of television contracts, solid legal covenants, low per club debt limits, positive league growth and fan initiatives, and peers.[48] An “A+” Fitch rating is equivalent to Moody’s “A1” grade and S&P’s “A+” grade.[49] Under NFL Ventures, LP, the organization has $375 million in senior notes, and by having senior notes, the NFL’s assessment rights come before the member clubs, adequate legal provisions and requirements, and reserve levels.[50] Other leagues have credit facilities as well, including the National Basketball Association with J.P. Morgan Chase, Major League Baseball with Bank of America, and the National Hockey League with Citigroup Private Bank.[51]

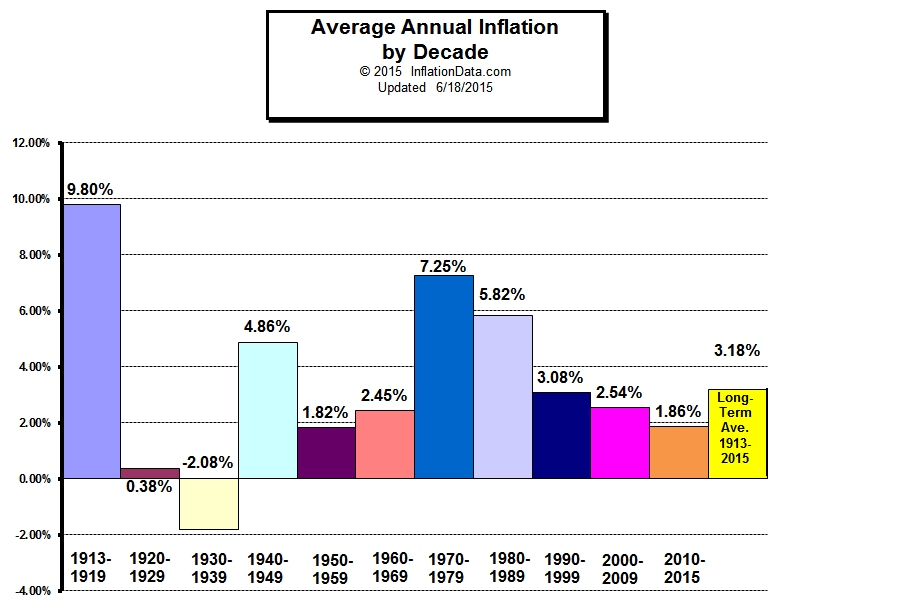

Another attractive feature of G-4 funding is that the cost of borrowing money under G-4 is normally less than the interest on a commercial loan, where G-4 implements an approximate two percent interest rate.[52] With inflation falling anywhere between two to three percent the last twenty years (1990-99: 3.00%; 2000-09: 2.56%; 2010-12: 2.29%),[53] the NFL essentially just wants their same buying power back with their money through G-4.

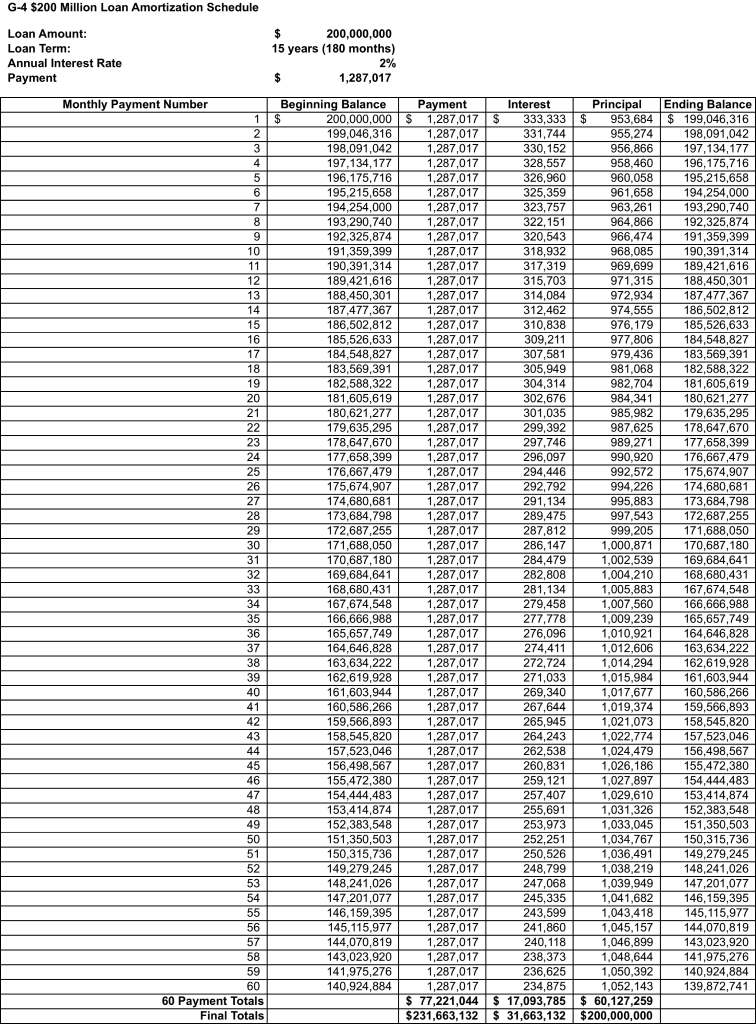

Financing through the NFL is currently a better option than securing a loan from a bank. As of February 1, 2016, the current interest rate for a fifteen-year, fixed rate loan is three and one-fourth (3.25) percent.[55] With the lower interest rate, the NFL creates an incentive for the teams to borrow money through the NFL rather than a bank, and the money from G-4 stays in the NFL. Below is an example of an amortization schedule for a team that borrows the maximum $200 million to construct a new stadium at a two percent interest rate under G-4 (only five years or sixty payments shown):

Financing through the NFL is currently a better option than securing a loan from a bank. As of February 1, 2016, the current interest rate for a fifteen-year, fixed rate loan is three and one-fourth (3.25) percent.[55] With the lower interest rate, the NFL creates an incentive for the teams to borrow money through the NFL rather than a bank, and the money from G-4 stays in the NFL. Below is an example of an amortization schedule for a team that borrows the maximum $200 million to construct a new stadium at a two percent interest rate under G-4 (only five years or sixty payments shown):

Overall, the NFL has experienced success with G-4. This is evidenced by the fact that ten NFL franchises have already been approved for a loan since 2011, and the NFL has received a high grade from Fitch Ratings. The current CBA runs through the 2020 season, so there is at least five more years of G-4.[56] NFL stadiums typically are thirty-one years old before they are replaced in favor of a new stadium;[57] therefore, the following stadiums are in line for possibly being replaced or renovated in the future:[58] Soldier Field (Chicago Bears, opened in 1924), Oakland Coliseum (Oakland Raiders, opened in 1966), Qualcomm Stadium (San Diego Chargers, opened in 1967), Arrowhead Stadium (Kansas City Chiefs, opened in 1972), Ralph Wilson Stadium (Buffalo Bills, opened in 1973), and the Mercedes-Benz Superdome (New Orleans Saints, opened in 1975). Because there is a possibility that at least six NFL franchises could be in need of a new stadium or stadium renovation, G-4 will very much remain active during the final five years of the current CBA.

Recently, the race to Los Angeles (LA) was ultimately decided in meetings on January 11 and 12, 2016, by NFL owners to permit the St. Louis Rams (Rams) to relocate to LA in 2016, which also impacted NFL subsidies to stadiums.[59] In those meetings, the NFL offered the San Diego Chargers (Chargers) and the Oakland Raiders (Raiders) an additional $100 million to assist those franchises in stadium solutions in their home markets.[60] Both the Chargers and the Raiders were in the running to relocate to LA as well, however, it is still possible for another team to relocate to LA.[61] Chargers owner Dean Spanos possesses an exercisable option that is valid until January 2017, which allows him to relocate to LA and join the Rams as either a partner or a tenant in the new Inglewood stadium that is expected to open for the 2019 NFL regular season.[62] If Spanos does not exercise his option, the Raiders will receive a one-year exercisable option to relocate to LA.[63] The Inglewood stadium is expected to cost about $3 billion, and could possibly receive two, $200 million G-4 loans from the NFL if another NFL franchise joins the Rams as either a partner or a tenant.[64]

Michael R. Gavin is currently a second-year law student at Marquette University, where he is focusing on Sports Law. In addition to being a 2017 Juris Doctor candidate, Gavin is also a 2017 Sports Law Certificate candidate at Marquette through the National Sports Law Institute. Gavin is a staff member of the Marquette Sports Law Review (Volume 26), and is a member of both the Sports Law Society and the Business Law Society at Marquette. Prior to Marquette, Gavin earned his bachelor of arts in Accounting from Washington & Jefferson College (Washington, PA), with a concentration in Entrepreneurial Studies. Outside of law school, Gavin is a practicing accountant at Building Control Parts, LLC, where he focuses on inventory control, and advises the firm on financial matters and operational processes.

[1] Lance Sabo, New Stadium Prospectus: Finance – Truth, Misconceptions & Consequences, Buffalo Rising (July 29, 2014), http://buffalorising.com/2014/07/new-stadium-prospectus-finance-truth-misconceptions-part-1-of-6/.

[2] Id.

[3] Id.

[4] Id.

[5] Id.

[6] Id.

[7] NFL Stadium Funding Information: Stadiums Opened Since 1997, Conventions Sports & Leisure (last visited Sept. 24, 2015), https://cbsminnesota.files.wordpress.com/2011/12/nfl-funding-summary-12-2-11.pdf.

[8] Id.

[9] About Us, MetLife Stadium, http://www.metlifestadium.com/stadium/about-us. (last visited Jan. 23, 2016).

[10] Matt Mosley, Jones Building a Legacy with $1.3 Billion Cowboys Stadium, ESPN (Sept. 18, 2008), http://sports.espn.go.com/nfl/columns/story?columnist=mosley_matt&page=hotread1/mosley.

[11] Mike Rosenberg, 49ers’ Kick Off Move to Santa Clara with Far-From-Traditional Groundbreaking, San Jose Mercury News (Apr. 19, 2012), http://www.mercurynews.com/southbayfootball/ci_20434376/49ers-break-ground-this-evening-stadium-at-center.

[12] US Bank Stadium – Information, Renderings and More of a Future Minnesota Vikings Stadium, Stadiums of Pro Football, http://www.stadiumsofprofootball.com/future/USBankStadium.htm. (last visited Jan. 23, 2016).

[13] City Councilmember Scott Sherman, Stadium Public/Private Partnerships, The City of San Diego, http://www.sandiego.gov/citycouncil/cd7/pdf/2015/release150401a3.pdf.

[14] Nathan Fenno, Stan Kroenke Seeks to Borrow about $1 Billion for Proposed Stadium in Inglewood, L.A. Times (Jan. 19, 2016), http://www.latimes.com/sports/la-sp-nfl-rams-financing-20160120-story.html.

[15] The G4 Stadium Program: G4 – How Does it Work?, Tatiana & Neha

Sports Finance (last visited Sept. 24, 2015), http://nkamalia.wix.com/fin320nfl#!g4/c10r4.

[16] Id.

[17] Scott R. Rosner & Kenneth L. Shropshire, The Business of Sports 167 (2d ed. 2010).

[18] Stefan Késenne & Juame García, Governance and Competition in Professional Sports Leagues 149 (2007).

[19] Id.

[20] Id.

[21] Rosner & Shropshire, supra note 17.

[22] Id.

[23] John Vrooman, The Economic Structure of the NFL, Vanderbilt University, http://www.vanderbilt.edu/econ/faculty/Vrooman/VROOMAN-NFL.pdf.

[24] John Vrooman, Dallas Cowboys Stadium Analysis, Vanderbilt University 22, http://www.vanderbilt.edu/econ/faculty/Vrooman/cowboys-estimate.pdf.

[25] 2011 NFL Lockout Timeline, CBS Sports (July 25, 2011), http://www.cbssports.com/mcc/blogs/entry/22475988/29591570.

[26] Id.

[27] The G4 Stadium Program: G4 – How Does it Work?, supra note 15.

[28] The National Football League & The National Football League Players Association, Collective Bargaining Agreement, NFL Players association, https://nflpaweb.blob.core.windows.net/media/Default/PDFs/General/2011_Final_CBA_Searchable_Bookmarked.pdf; Section 4. Stadium Credit, CBA Resource, http://cbaresource.com/articles/article-12-revenue-accounting-and-calculation-of-the-salary-cap/section-4-stadium-credit. (last visited Jan. 26, 2016).

[29] Matthew T. Hall, Details on NFL Revival of its Stadium Loan Program, SDuncovered (Dec. 14, 2011), http://sduncovered.tumblr.com/post/14237798043/details-on-nfl-revival-of-its-stadium-loan-program.

[30] NFL on Its New Stadium Loan Program, signonsandiego.com, http://media.signonsandiego.com/news/documents/2011/12/14/NFL_on_its_new_stadium_loan_program.pdf. (last visited Jan. 23, 2016).

[31] Sabo, supra note 1.

[32] The G4 Stadium Program: G4 – How Does it Work?, supra note 15; Daniel Kaplan, NFL Projecting Revenue Increase of $1B over 2014, Street & Smith’s Sports Business Journal (Mar. 9, 2015), http://www.sportsbusinessdaily.com/Journal/Issues/2015/03/09/Leagues-and-Governing-Bodies/NFL-revenue.aspx.

[33] Sabo, supra note 1.

[34] Neil deMause, NFL Establishes “G-4” Stadium Fund, There Is Much Rejoicing, Field of Schemes (Dec. 20, 2011), http://www.fieldofschemes.com/news/archives/2011/12/4761_nfl_establishes.html.

[35] John Vrooman, NFL G-3/4 Stadium Loan Program, Vanderbilt University (last visited Sept. 24, 2015), http://www.vanderbilt.edu/econ/faculty/Vrooman/credit-facilities.pdf.

[36] Blank Issues Statement on NFL G-4 Stadium Financing Approval, Atlanta Falcons (May 21, 2013), http://www.atlantafalcons.com/news/article-1/Blank-Issues-Statement-on-NFL-G-4-Stadium-Financing-Approval/fd34f37f-ea96-4622-9627-676946cf0140.

[37] Marine Layer, The Limits of the NFL’s G-4 Stadium Loan Program, newballpark.org (Oct. 17, 2013), http://newballpark.org/2013/10/17/the-limits-of-the-nfls-g-4-stadium-loan-program/.

[38] NFL Approves Stadium Renovations in Washington and Cleveland, NFL.com (Oct. 8, 2013), http://www.nfl.com/news/story/0ap2000000258979/article/nfl-approves-stadium-renovations-in-washington-and-cleveland.

[39] Associated Press, Green Bay Packers’ Funding to Improve Lambeau Granted by NFL, NFL (Oct. 23, 2012), http://www.nfl.com/news/story/0ap1000000084337/article/green-bay-packers-funding-to-improve-lambeau-granted-by-nfl.

[40] Fenno, supra note 14.

[41] Doug Hanks, NFL Chipping in $50 Million for $425 Million Sun Life Renovation, Naked Politics (Jan. 10, 2015), http://miamiherald.typepad.com/nakedpolitics/2015/01/nfl-chipping-in-50-million-for-425-million-sun-life-renovation.html.

[42] Christopher Gates, Minnesota Vikings Stadium: Team Gets G4 Loan From NFL, Daily Norseman (Mar. 18, 2013), http://www.dailynorseman.com/2013/3/18/4121552/minnesota-vikings-stadium-team-gets-g4-loan-from-nfl.

[43] Howard Mintz, NFL Owners Approve $200 million Loan for 49ers Stadium, San Jose Mercury News (Feb. 3, 2012), http://www.mercurynews.com/ci_19878108.

[44] NFL Approves Stadium Renovations in Washington and Cleveland, supra note 38.

[45] Maya Burchette, Stadium Renovations Grow In Importance For NFL Teams’ Super Bowl Bids, Ruling Sports (June 11, 2013), http://rulingsports.com/2013/06/11/stadium-renovations-grow-in-importance-for-nfl-teams-super-bowl-bids/.

[46] Fitch Rates NFL Ventures’ G-4 Notes ‘A+’; Affirms Outstanding; Outlook Stable, Fitch Ratings (June 26, 2015), https://www.fitchratings.com/site/fitch-home/pressrelease?id=987100.

[47] Multiple-Markets, http://multiple-markets.com/3ratingschart.htm (last visited Sept. 24, 2015).

[48] Id.

[49] QuadCapital Advisors, LLC, http://www.quadcapital.com/Rating%20Agency%20Credit%20Ratings.pdf (last visited Sept. 24, 2015).

[50] Id.

[51] Vrooman, supra note 35.

[52] Id.

[53] Tim McMahon, Long Term U.S. Inflation, InflationData.com (Apr. 1, 2014), http://inflationdata.com/Inflation/Inflation_Rate/Long_Term_Inflation.asp.

[54] Average Annual US Inflation by Decade, InflationData.com, http://inflationdata.com/articles/charts/decade-inflation-chart/. (last visited Jan. 28, 2016).

[55] Wells Fargo, https://www.wellsfargo.com/mortgage/rates/ (last visited Feb. 1, 2016).

[56] Gregg Rosenthal, The CBA in a Nutshell, ProFootballTalk (July 25, 2011), http://profootballtalk.nbcsports.com/2011/07/25/the-cba-in-a-nutshell/.

[57] Chris Isidore, NFL Stadiums: Higher Costs, Shorter Lifespans, CNN Money (Sept. 8, 2014), http://money.cnn.com/2014/09/08/news/companies/nfl-stadiums/.

[58] List of Current National Football League Stadiums, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_current_National_Football_League_stadiums. (last visited Nov. 3, 2015).

[59] Paul Gutierrez, What’s next for the once-and-still Oakland Raiders?, Oakland Raiders Blog – ESPN (Jan. 13, 2016), http://espn.go.com/blog/oakland-raiders/post/_/id/14072/whats-next-for-the-once-and-still-oakland-raiders.

[60] Chris Wesseling, NFL to Offer Chargers, Raiders Assistance Package, NFL.com (Jan. 13, 2016), http://www.nfl.com/news/story/0ap3000000621719/article/nfl-to-offer-chargers-raiders-assistance-package.

[61] Id.

[62] Id.

[63] Id.

[64] Fenno, supra note 14.

[54]

[54]