By Martin J. Greenberg and Henry Twomey

I. Sports Stars Are Natural Prey for Investment Scams

Professional athletes are among the most common group of individuals to become victims of investment fraud and scams. After numerous reports of fraud cases, athletes continue to find themselves in financial situations that result in astronomical losses. This begs the obvious question, why?

Professional athletes are among the most common group of individuals to become victims of investment fraud and scams. After numerous reports of fraud cases, athletes continue to find themselves in financial situations that result in astronomical losses. This begs the obvious question, why?

For starters, many professional athletes dedicate their entire lives to their sport in order to perform at an elite level. With little free time left to explore other interests, athletes are often unsophisticated in the world of business and investments. This leaves athletes vulnerable to investment managers who have total control over their funds.[1] Professional athletes are prime targets in that they often are unsophisticated and have large amounts of cash ready to be invested.[2] The sports industry at both the professional and amateur level produces large sums of money that change hands on a daily basis. Lack of time to do their own due diligence, misplaced trust in untrustworthy advisors, and seemingly endless amounts of money make professional athletes prime targets of investment scams.

Athletes run into many of the same financial problems that ordinary people do, except with a lot more to lose. Filing for bankruptcy is not uncommon and the causes therefor are multiple, including: “(1) spending like a drunken sailor as if the checks will never stop; (2) creating unsustainable lifestyles; 3) buying houses the size of Texas; 4) diamonds and automobiles seem to be the favorite consumables; 5) risky and sometimes even inane “investments,” such as inflatable furniture rafts, sonic rays, music labels, nightclubs, T-shirt companies, cosmetic procedures and Ponzi schemes; 6) a chronic misallocation of investment dollars into nonliquid assets and private equity deals; 7) misplaced trust and agent mismanagement; 8) granting powers of attorney; 9) divorce and paternity actions; and 10) supporting enablers.”[3]

Athletes run into many of the same financial problems that ordinary people do, except with a lot more to lose. Filing for bankruptcy is not uncommon and the causes therefor are multiple, including: “(1) spending like a drunken sailor as if the checks will never stop; (2) creating unsustainable lifestyles; 3) buying houses the size of Texas; 4) diamonds and automobiles seem to be the favorite consumables; 5) risky and sometimes even inane “investments,” such as inflatable furniture rafts, sonic rays, music labels, nightclubs, T-shirt companies, cosmetic procedures and Ponzi schemes; 6) a chronic misallocation of investment dollars into nonliquid assets and private equity deals; 7) misplaced trust and agent mismanagement; 8) granting powers of attorney; 9) divorce and paternity actions; and 10) supporting enablers.”[3]

Additionally, the career of a professional athlete often happens quickly, a short-term life, resulting in a rapid accumulation of a large amount of money. Some unscrupulous advisors see this as an opportunity to “manage” these finances when in actuality the athlete’s money is being placed in high-risk investments that produce equally high commissions for the advisor, with little long-term return or safety for the athlete.[4] Advisors often recognize the athletic potential at the college level and begin to target players through loopholes around the NCAA prohibitions on consulting with college athletes. However, the main issue comes “post-life,” or after athletics end. When the bright lights in the stadium and arenas go off for good, players lose their identity and have no retirement plan to help them find one.[5]

II. Notorious Athlete Blunders

Athlete scams have been a staple of professional sports for decades and are not reserved for lesser-known athletes. Typically, these advisors are trusted friends and family members who have no investment credibility to take control of the athlete’s finances. In some instances, athlete advisors will pretend to have strong business acumen, and in fact are merely using the athletes’ funds on risky investments that they themselves could not afford. Michael Fuchs, a lawyer for the SEC in the infamous case against former agent William H. “Tank” Black stated “professional athletes are prime candidates for financial fraud. Many are unsophisticated in financial matters and suddenly find themselves in a six or seven-figure salary. They’re young, they’re trusting, and they’ve been taken care of for most of their lives.”[6]

The Tank Black scandal is one of the most notorious examples of deceit and financial mismanagement by a financial advisor in sports history. Former sports agent William “Tank” Black was at one point the most prominent sports agent in the country, representing NFL players such as Fred Taylor, Terry Allen, Rae Curreth, and NBA superstar Vince Carter, to name a few.[7] In 2002, Black was convicted of charges in which he lost several of his former clients a combined $12 million.[8] In 2004, Black pleaded guilty to conspiracy to commit money laundering and was sentenced to 51 months in federal prison, a total of six and a half years.[9] He was also sentenced to pay restitution to his victims of at least $250 per month for three years following his prison sentence.[10]

The Tank Black scandal is one of the most notorious examples of deceit and financial mismanagement by a financial advisor in sports history. Former sports agent William “Tank” Black was at one point the most prominent sports agent in the country, representing NFL players such as Fred Taylor, Terry Allen, Rae Curreth, and NBA superstar Vince Carter, to name a few.[7] In 2002, Black was convicted of charges in which he lost several of his former clients a combined $12 million.[8] In 2004, Black pleaded guilty to conspiracy to commit money laundering and was sentenced to 51 months in federal prison, a total of six and a half years.[9] He was also sentenced to pay restitution to his victims of at least $250 per month for three years following his prison sentence.[10]

It is reported that Black lost $3.6 million of Fred Taylor’s money in a series of scams in the late 1990s.[11] It was also alleged that former NFL players Jacquez Green and Germane Crowell each lost $500,000 through Black’s mismanagement. Black’s mismanagement was centered around his South Carolina based company, Professional Marketing Incorporated (PMI).[12] The center of Black’s scandal was based on his relationship with a California based company called Black Americans of Achievement (BAOA).[13] Black convinced members of BAOA to approve a consulting agreement where a select few of his clients at PMI received shares of the BAOA stock for promotional services.[14] However, Black never informed his clients of this deal.[15] Black would then fraudulently claim that his clients had done work on behalf of BAOA, and with the shares in hand, would sell them to his clients at an inflated price.[16] Once his clients purchased the stock, Black would have them write the checks payable to PE Communications, a corporate shell he had created before he transferred the money into his own personal account.[17] A financial scam of this magnitude is a valuable tool for current players to learn from others mistakes.

The Tank Black financial scam was likely the most significant financial mismanagement of professional athletes’ fortunes to date. However, financial mismanagement has been a problem for professional athletes for years. Kareem Abdul-Jabbar (Abdul-Jabbar) fell victim to a major financial setback in the 1980s at the hands of his sports agent, Tom Collins (Collins).[18] Collins served as Abdul-Jabbar’s agent, business manager, and investment advisor from 1980 until 1986.[19] In that short time, Collins had taken out more than $9 million in loans under Abdul-Jabbar’s name, transferred Abdul-Jabbar’s money to pay other clients, and had made risky investments with Abdul-Jabbar’s money.[20] For example, Collins invested Abdul-Jabbar’s earnings in a Texas rib restaurant, a hotel in Alabama, two hotels and a restaurant in California, an exercise rope, a sports club, a limousine service, a commodities brokerage, and a cattle feed business.[21] In an interview with Sports Illustrated, Abdul-Jabbar noted that the biggest mistake he made was giving Collins full power of attorney, and failing to request monthly statements from Collins regarding the ongoing details of their agreement.[22] Abdul-Jabbar only became aware of his financial issues when the IRS provided him with notice that he had not paid his taxes for two years.[23] Reflecting on his financial mistakes, Abdul-Jabbar stated “[i]t’s been a crash course in business school and I’ve paid a steep tuition.”[24] Although Abdul-Jabbar was the main focus, Collins also allegedly mismanaged money of other players such as Ralph Sampson of the Houston Rockets, Terry Cummings of the Milwaukee Bucks, Alex English of the Denver Nuggets, and Brad Davis of the Dallas Mavericks.[25]

The Tank Black financial scam was likely the most significant financial mismanagement of professional athletes’ fortunes to date. However, financial mismanagement has been a problem for professional athletes for years. Kareem Abdul-Jabbar (Abdul-Jabbar) fell victim to a major financial setback in the 1980s at the hands of his sports agent, Tom Collins (Collins).[18] Collins served as Abdul-Jabbar’s agent, business manager, and investment advisor from 1980 until 1986.[19] In that short time, Collins had taken out more than $9 million in loans under Abdul-Jabbar’s name, transferred Abdul-Jabbar’s money to pay other clients, and had made risky investments with Abdul-Jabbar’s money.[20] For example, Collins invested Abdul-Jabbar’s earnings in a Texas rib restaurant, a hotel in Alabama, two hotels and a restaurant in California, an exercise rope, a sports club, a limousine service, a commodities brokerage, and a cattle feed business.[21] In an interview with Sports Illustrated, Abdul-Jabbar noted that the biggest mistake he made was giving Collins full power of attorney, and failing to request monthly statements from Collins regarding the ongoing details of their agreement.[22] Abdul-Jabbar only became aware of his financial issues when the IRS provided him with notice that he had not paid his taxes for two years.[23] Reflecting on his financial mistakes, Abdul-Jabbar stated “[i]t’s been a crash course in business school and I’ve paid a steep tuition.”[24] Although Abdul-Jabbar was the main focus, Collins also allegedly mismanaged money of other players such as Ralph Sampson of the Houston Rockets, Terry Cummings of the Milwaukee Bucks, Alex English of the Denver Nuggets, and Brad Davis of the Dallas Mavericks.[25]

In recent years, athletes such as Torii Hunter, Tim Duncan, Clinton Portis, John Elway, and Horace Grant have all been victims of advisor and agent misdealing’s that have led to millions of dollars in losses. According to Sports Illustrated, Torii Hunter once invested $70,000 in an inflatable raft invention that would allow sofas to float and remain dry in high-rainfall areas.[26] When the investor followed up wanting Hunter to put in $500,000 more into the invention, Hunter knew he was involved in a scam.[27]

John Elway invested $15 million with a co-investor in what resulted in a Ponzi scheme organized by hedge fund manager Sean Mueller (Mueller).[28] Mueller collected funds exceeding $70 million from a group of sixty investors.[29]

John Elway invested $15 million with a co-investor in what resulted in a Ponzi scheme organized by hedge fund manager Sean Mueller (Mueller).[28] Mueller collected funds exceeding $70 million from a group of sixty investors.[29]

Michael Vick recently filed Chapter 11 bankruptcy and was forced to sell his Atlanta home after he was unable to repay $6 million in loans.[30] The loans were taken out to invest in numerous business ventures, including a car-rental business, a real estate venture in Canada, and a wine business.[31]

Darren McCarty, former defenseman of the Detroit Red Wings, was the victim of an untrustworthy business partner. The partner took $3 million out of McCarty’s personal checking account and also forged McCarty’s signature on a check for $650,000.[32]

Darren McCarty, former defenseman of the Detroit Red Wings, was the victim of an untrustworthy business partner. The partner took $3 million out of McCarty’s personal checking account and also forged McCarty’s signature on a check for $650,000.[32]

In 2015, Tim Duncan filed a lawsuit against his former financial advisor alleging that he lost more than $20 million due to fraudulent investments.[33] Charlie Banks, the former advisor, is accused of investing Duncan’s funds despite conflicts of interests that ultimately resulted in a major economic loss.[34]

Darren McFadden (McFadden), a running back for the Dallas Cowboys, filed a $15 million lawsuit against his longtime business manager, Michael Vick (Vick).[35] McFadden alleges that Vick used fraudulent documents to gain a power of attorney and fabricated financial records.[36] The lawsuit states: “[r]ather than securing for Plaintiff a lifetime of financial security as Defendant Vick promised Plaintiff, Defendant Vick covertly used Plaintiff’s income as his personal slush fund to subsidize his own lifestyle and expenses and to invest in his own projects.”[37] In an interview with the Dallas Morning News, McFadden stated:

Darren McFadden (McFadden), a running back for the Dallas Cowboys, filed a $15 million lawsuit against his longtime business manager, Michael Vick (Vick).[35] McFadden alleges that Vick used fraudulent documents to gain a power of attorney and fabricated financial records.[36] The lawsuit states: “[r]ather than securing for Plaintiff a lifetime of financial security as Defendant Vick promised Plaintiff, Defendant Vick covertly used Plaintiff’s income as his personal slush fund to subsidize his own lifestyle and expenses and to invest in his own projects.”[37] In an interview with the Dallas Morning News, McFadden stated:

Vick was an old family friend that we knew growing up forever and ended up trusting him to do my finances and it didn’t work out right for me. It’s just one of those deals with me as a young guy I wasn’t on top of my finances like I should have been and I trusted somebody to take care of everything for me and I don’t feel like at the time he had my best interest.[38]

In addition to the common trend of individual scams, often athlete scams involve a group of professional athletes that are convinced to invest in the same venture. In 2013, the FBI began to investigate a potential $18 million scam involving Jade Wealth Management (Jade) and Success Trade Securities (STS).[39] Jade controlled dozens of financial investments for professional athletes including ties to STS.[40] Yahoo! Sports reported that the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) began an investigation of STS after the firm “allegedly sold $18 million in fraudulent and unregistered promissory notes to 58 persons, many of whom were NFL and NBA players.”[41] Among the athletes that purchased the promissory notes from Success Trade via were: Detroit Pistons guard Brandon Knight, Cleveland Browns cornerback Joe Haden, San Francisco 49ers tight end Vernon Davis, former Washington Redskins running back Clinton Portis, and former Chicago Bears defensive end Adewale Ogunleye.[42] These are just a few names reported by Yahoo! Sports, who suggest that more than thirty clients of Jade purchased the fraudulent notes, with investments ranging from $50,000 to more than $500,000.[43] In an interview with Yahoo! Sports Jade founder Jinesh Brahmbhatt stated, “I just hope nobody says, ‘the guys at Jade capitalized on this,’ because we never did. Other than the first year we took [$1.25 million] from him [. . .] everything we did for him is because we actually liked it.”[44] On June 25, 2014, FINRA announced that their hearing panel had “expelled Washington, D.C.-based Success Trade Securities, Inc. from membership and barred its CEO and President Fuad Ahmed, for the fraudulent sale of promissory notes and for creating a Ponzi scheme.”[45]

In addition to the common trend of individual scams, often athlete scams involve a group of professional athletes that are convinced to invest in the same venture. In 2013, the FBI began to investigate a potential $18 million scam involving Jade Wealth Management (Jade) and Success Trade Securities (STS).[39] Jade controlled dozens of financial investments for professional athletes including ties to STS.[40] Yahoo! Sports reported that the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) began an investigation of STS after the firm “allegedly sold $18 million in fraudulent and unregistered promissory notes to 58 persons, many of whom were NFL and NBA players.”[41] Among the athletes that purchased the promissory notes from Success Trade via were: Detroit Pistons guard Brandon Knight, Cleveland Browns cornerback Joe Haden, San Francisco 49ers tight end Vernon Davis, former Washington Redskins running back Clinton Portis, and former Chicago Bears defensive end Adewale Ogunleye.[42] These are just a few names reported by Yahoo! Sports, who suggest that more than thirty clients of Jade purchased the fraudulent notes, with investments ranging from $50,000 to more than $500,000.[43] In an interview with Yahoo! Sports Jade founder Jinesh Brahmbhatt stated, “I just hope nobody says, ‘the guys at Jade capitalized on this,’ because we never did. Other than the first year we took [$1.25 million] from him [. . .] everything we did for him is because we actually liked it.”[44] On June 25, 2014, FINRA announced that their hearing panel had “expelled Washington, D.C.-based Success Trade Securities, Inc. from membership and barred its CEO and President Fuad Ahmed, for the fraudulent sale of promissory notes and for creating a Ponzi scheme.”[45]

Also in 2013, the FBI indicted and subsequently convicted Phillip A. Kenner (Kenner) and Tommy C. Constantine (Constantine) for wire fraud, conspiracy, and money laundering that involved numerous National Hockey League (NHL) players. Kenner, a financial advisor, and Constantine, a former professional racecar driver, were charged and convicted of advising numerous NHL players on fraudulent investments that resulted in losses exceeding $15 million.[46] The first scam involved a real estate investment on the Big Island of Hawaii.[47] Kenner convinced more than thirteen NHL players to each invest more than $100,000 in the development project.[48] In actuality, Kenner and Constantine used the funds for personal real estate purchases, expenses, and other personal debt unrelated to any group venture.[49] The total loss suffered by the victims exceeded $13 million.[50]

Also in 2013, the FBI indicted and subsequently convicted Phillip A. Kenner (Kenner) and Tommy C. Constantine (Constantine) for wire fraud, conspiracy, and money laundering that involved numerous National Hockey League (NHL) players. Kenner, a financial advisor, and Constantine, a former professional racecar driver, were charged and convicted of advising numerous NHL players on fraudulent investments that resulted in losses exceeding $15 million.[46] The first scam involved a real estate investment on the Big Island of Hawaii.[47] Kenner convinced more than thirteen NHL players to each invest more than $100,000 in the development project.[48] In actuality, Kenner and Constantine used the funds for personal real estate purchases, expenses, and other personal debt unrelated to any group venture.[49] The total loss suffered by the victims exceeded $13 million.[50]

Next, the duo set their focus on Eufora, LLC, a prepaid debit card business. Kenner again convinced his NHL clients to invest $1.4 million into the company.[51] However, Constantine and Kenner used the investment to pay off personal mortgages, credit card bills, travel, and jewelry expenses.[52] The NHL victims, along with a few other investors, lost more than $1.5 million.[53]

For much of 2009, Constantine and Kenner persuaded more NHL investors to place funds into an attorney’s escrow account called the Global Settlement Fund.[54] Constantine and Kenner convinced the investors that the fund was to be used to finance litigation involving Mexican land deals.[55] The duo raised $4.1 million, most of which went directly to Constantine’s personal bank accounts.[56] Kenner used a portion of the money to personally invest in a tequila company.[57] The remaining funds went towards litigation involving Constantine’s racecar company and the transfer of Constantine’s home. Total loss from this investment exceeded $1 million.[58]

The final scheme, which ultimately exposed Kenner and Constantine, was a real estate transaction funded exclusively through an NHL player’s line of credit without his knowledge.[59] Another player was promised a fifty percent interest in the deal, and only received twenty five percent.[60] Once the investors understood the scam, they sold the property at a loss.[61] Assistant Director George Venizelos of the FBI characterized Kenner and Constantine activities as follows: “[a]s alleged, Kenner exploited his personal relationship with these players in pursuit of his own lucre. Player after player, time after time, he and his partner, Constantine, stole from anyone they could find. This was an elaborate scheme of deception, trickery, and lies that victimized many [. . .].”[62]

Constantine and Kenner are not the only financial advisors that have manipulated and defrauded a large group of trusted clientele.

Constantine and Kenner are not the only financial advisors that have manipulated and defrauded a large group of trusted clientele.

A recent court decision from the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York held that a financial advisor will pay more than $1.9 million in damages for similar conduct.[63] A final judgment entered in favor of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission concluded that Louis Martin Blazer III, a Pittsburgh-based financial adviser and founder of Blazer Capital Management, defrauded clients by using $2.35 million of their money without authorization.[64] In its complaint, the SEC claimed that Blazer invested in a pair of movies, and falsified documents in an attempt to cover up the fraud.[65] Judge Paul Oetken, who signed the final judgment, stated that “by making this payment, defendant relinquishes all legal and equitable right, title, and interest in such funds and no part of the funds shall be returned to the defendant.”[66]

The details of Blazer’s financial mismanagement of his clients, many whom were professional athletes, exemplify how financial advisors are using non-traditional and innovative methods to scam clients out of substantial amounts of money. According to the 2016 complaint, Blazer took $550,000 from one of his clients to invest in a film project.[67] However, the client already declined to invest in the film, so Blazer forged documents in order to complete the transaction.[68] Once the first client discovered the transaction and rightfully sought reimbursement, Blazer used unauthorized money from a second client to repay the first client while investing the remaining money from the second client in a music venture.[69] By the end of the investigation, the SEC described Blazer’s investments as “Ponzi-like,” and accused Blazer of taking a total of $2.35 million from five clients without authorization.[70]

The details of Blazer’s financial mismanagement of his clients, many whom were professional athletes, exemplify how financial advisors are using non-traditional and innovative methods to scam clients out of substantial amounts of money. According to the 2016 complaint, Blazer took $550,000 from one of his clients to invest in a film project.[67] However, the client already declined to invest in the film, so Blazer forged documents in order to complete the transaction.[68] Once the first client discovered the transaction and rightfully sought reimbursement, Blazer used unauthorized money from a second client to repay the first client while investing the remaining money from the second client in a music venture.[69] By the end of the investigation, the SEC described Blazer’s investments as “Ponzi-like,” and accused Blazer of taking a total of $2.35 million from five clients without authorization.[70]

In the complaint, the SEC specifically alleged the following:

This case concerns a fraudulent scheme executed by Blazer to surreptitiously take money from his clients to make unauthorized risky investments, to repay clients who lodged complaints concerning how their funds had been invested and sought a return of their money, or to fund investments made in the name of a Blazer controlled entity. In total, Blazer took $2,350,000 from five clients in unauthorized transactions.

Blazer is the founder, owner, and operator of Blazer Capital Management, LLC (“Blazer Capital”), a Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania-based personal services or “concierge” firm that targeted as clients professional athletes and other high net worth individuals. In 2008, Blazer also founded an affiliated registered investment advisory firm, Blazer Investment Advisors, LLC (“Blazer Advisors”), to provide investment related services to his clients. In 2012, Blazer co-founded another registered investment advisory firm (“Investment Advisory Firm l”) and transitioned many of his clients to that firm from Blazer Advisors.

Between 2010 and 2012, Blazer repeatedly took money from his clients to invest without authorization in two movie projects in which Blazer had a financial interest. In 2010, Blazer agreed to raise money for two film projects, “Mafia the Movie” and “Sibling.” The production company for each project was a limited liability company (“LLC”)-Sibling the Movie, LLC (“Sibling LLC”) and Mafia the Movie, LLC (“Mafia LLC”)-with the plan being that investors would purchase LLC interests in each. Blazer initially planned to raise at least $1 million to finance these movie ventures. Although Blazer convinced some of his clients to invest in the projects, he was unable to raise the full amount needed to complete production of the two films. To compensate for the shortfall, Blazer simply took funds from client accounts over which he had control, and used the money to finance the films.

In one instance, Blazer pitched a client who was then a professional athlete (“Client l”) about an investment in the film projects. Client 1 refused to make the investment. Despite that, Blazer took $550,000 from Client l’s account and purchased LLC interests in Mafia the Movie and Sibling. To transfer the money out of Client l’s account, Blazer drafted forged documents and submitted them to Client 1’s brokerage firm to make it appear as if Client 1 had authorized the transfer.

Blazer also made Ponzi-like payments by making unauthorized transfers out of one client’s accounts to repay another client seeking a return of his money. In 2012, after Client 1 discovered that Blazer had made the $550,000 investment in the film projects without Client l’s authorization, Client 1 demanded his money back from Blazer and threatened legal action if Blazer was unable to return the money. To make Client 1 whole, Blazer took money without authorization from yet another client who was also a professional athlete (“Client 2”). Blazer forged Client 2’s signature and used the forged documents to transfer $650,000 from Client 2’s accounts without authorization. Blazer used $550,000 of Client 2’s money to repay Client 1 by structuring the transaction as if Client 2 had purchased Client l’s LLC interests in the two movie projects, and the remaining $100,000 to fund an investment in the name of Blazer Capital in a music venture.

In 2013, Blazer also made false statements to the Commission’s examination staff (“Exam Staff’) in order to conceal his fraud. During an inspection of Investment Advisory Firm 1, Exam Staff identified the suspicious transactions through Blazer Capital accounts involving Client 1 and Client 2. When questioned about these transactions, Blazer told the Exam Staff that both clients had authorized the investments. Blazer, in fact, concocted a story that he put Client 1 in touch with Client 2 regarding the movies, and the two clients negotiated their own deal. Blazer then prepared written responses to questions from the Exam Staff, which incorporated those lies. Blazer also manufactured fake documents in an attempt to create documentation for the supposed transactions. In fact, neither Client 1 nor Client 2 approved any transaction relating to the investment of their funds in any movie projects or music venture.[71]

The SEC claimed that Blazer was in violation of Sections 17(a)(1) and 17(a)(3) of the Securities Act, Section 10(b) and Rules 10b-5(a) and (c) of the Exchange Act, and Section 206(1) and 206(2) of the Advisers Act.[72]

The final judgment, entered on August 4, 2017, ordered Blazer to pay $1.8 million in disgorgement and prejudgment interest and a civil penalty of $150,000.[73] The partial judgment by consent, imposing a permanent industry ban, states the following:

The final judgment, entered on August 4, 2017, ordered Blazer to pay $1.8 million in disgorgement and prejudgment interest and a civil penalty of $150,000.[73] The partial judgment by consent, imposing a permanent industry ban, states the following:

The Securities and Exchange Commission (“Commission”) deems it appropriate and in the public interest that public administrative proceedings be, and hereby are, instituted pursuant to Section 203(f) of the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 (“Advisers Act”) against Louis Martin Blazer III (“Respondent”).

In anticipation of the institution of these proceedings, Respondent has submitted an Offer of Settlement (the “Offer”) which the Commission has determined to accept. Solely for the purpose of these proceedings and any other proceedings brought by or on behalf of the Commission, or to which the Commission is a party, and without admitting or denying the findings herein, except as to the Commission’s jurisdiction over him and the subject matter of these proceedings and the findings contained in paragraphs III.B.2 below, which are admitted, Respondent consents to the entry of this (“Order”), as set forth below.

Respondent, age 45, resides in Clinton, Pennsylvania. Starting in 2008, Respondent was an officer and partial owner of Blazer Investment Advisors, LLC (“Blazer Advisors”), which was registered with the Commission from February 23, 2010 through March 29, 2012. From September 2011 through September 2013, Respondent was an officer and partial owner of “Investment Advisory Firm 1”, which has been registered with the Commission as an investment advisory firm since January 2012.

On May 18, 2016, a partial final judgment was entered by consent against Respondent, permanently enjoining him from future violations of Section 17(a) of the Securities Act of 1933, Section 10(b) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 and Rule 10b-5 thereunder, and Sections 206(1) and 206(2) of the Advisers Act, in the civil action entitled Securities and Exchange Commission v. Louis Martin Blazer III, Civil Action Number 1:16-CV-3384 (JPO), in the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York.

The Commission’s complaint alleged that Respondent misused and misappropriated client funds to invest in risky ventures that Respondent had a financial interest in, to invest on Respondent’s behalf, or to pay back other clients from whom Respondent took money without authorization for such investments.

In view of the foregoing, the Commission deems it appropriate and in the public interest to impose the sanctions agreed to in Respondent Blazer’s Offer. Accordingly, it is hereby ORDERED pursuant to Section 203(f) of the Advisers Act that Respondent Blazer be, and hereby is barred from association with any broker, dealer, investment adviser, municipal securities dealer, municipal advisor, transfer agent, or nationally recognized statistical rating organization; Any reapplication for association by the Respondent will be subject to the applicable laws and regulations governing the reentry process, and reentry may be conditioned upon a number of factors, including, but not limited to, the satisfaction of any or all of the following: (a) any disgorgement ordered against the Respondent, whether or not the Commission has fully or partially waived payment of such disgorgement; (b) any arbitration award related to the conduct that served as the basis for the Commission order; (c) any self-regulatory organization arbitration award to a customer, whether or not related to the conduct that served as the basis for the Commission order; and (d) any restitution order by a self-regulatory organization, whether or not related to the conduct that served as the basis for the Commission order.[74]

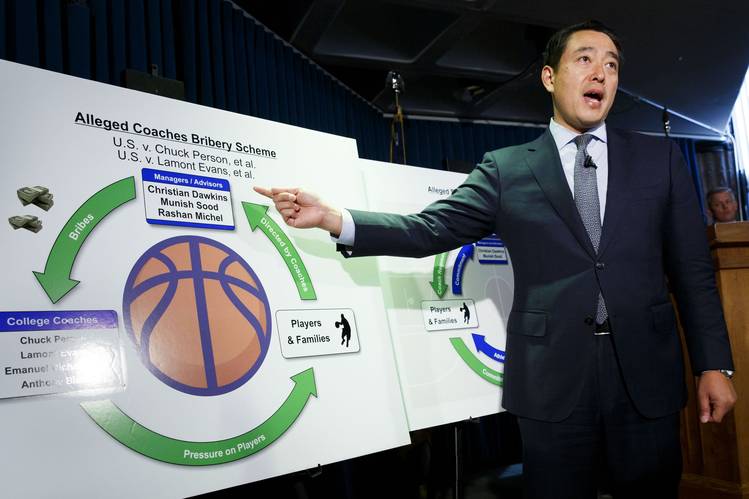

In September of 2017 it was revealed that Blazer was a key witness in an NCAA basketball scandal.[75] Blazer’s plea agreement was revealed “as the FBI arrested 10 people, including four NCAA basketball coaches, from Arizona, Auburn, Oklahoma State and Southern California.”[76] The criminal case filed by the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York involves fraud and other charges against coaches and other participants connected with NCAA basketball and alleges that the coaches took bribes among other charges.[77] Under the plea agreement, Blazer, who faces up to 67 years in jail for five criminal counts, will not be prosecuted for those claims and other alleged crimes if he cooperates with the government.[78] “Blazer had been working with federal authorities for over a year investigating allegations that college coaches were accepting bribes to steer basketball players to certain companies, managers and financial advisors after the players became professionals, the U.S. Attorney’s office said.”[79] In the criminal complaints, Blazer is identified by CW-1, or “cooperating witness-1.”[80] The complaints allege the following bribes were paid by Blazer or associates in exchange for the coaches agreeing to put in a good word about utilizing Blazer’s services to students who were entering the NBA:

In September of 2017 it was revealed that Blazer was a key witness in an NCAA basketball scandal.[75] Blazer’s plea agreement was revealed “as the FBI arrested 10 people, including four NCAA basketball coaches, from Arizona, Auburn, Oklahoma State and Southern California.”[76] The criminal case filed by the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York involves fraud and other charges against coaches and other participants connected with NCAA basketball and alleges that the coaches took bribes among other charges.[77] Under the plea agreement, Blazer, who faces up to 67 years in jail for five criminal counts, will not be prosecuted for those claims and other alleged crimes if he cooperates with the government.[78] “Blazer had been working with federal authorities for over a year investigating allegations that college coaches were accepting bribes to steer basketball players to certain companies, managers and financial advisors after the players became professionals, the U.S. Attorney’s office said.”[79] In the criminal complaints, Blazer is identified by CW-1, or “cooperating witness-1.”[80] The complaints allege the following bribes were paid by Blazer or associates in exchange for the coaches agreeing to put in a good word about utilizing Blazer’s services to students who were entering the NBA:

- Assistant coach Person of Auburn University allegedly solicited and obtains $91,000 in bribes;

- Assistant coach Evans at Oklahoma State University allegedly solicited at least $22,000 in bribes; and

- Assistant coach Emanuel “Book” Richardson at the University of Arizona allegedly accepted $20,000 in bribes from undercover law enforcement agents in a sting operation.[81] These cases are currently pending.

III. Ash Narayan Case

On May 24, 2016, the SEC filed a lawsuit against Ash Narayan, an investment advisor who is alleged to have scammed numerous professional athletes out of millions of dollars.[82] Shamoil T. Shipchandler, Director of the SEC’s Fort Worth Regional Office stated, “[w]e allege that Narayan exploited athletes and other clients who trusted him to manage their finances. He fraudulently funneled their savings into a money-losing business and his own pocket.”[83]

On May 24, 2016, the SEC filed a lawsuit against Ash Narayan, an investment advisor who is alleged to have scammed numerous professional athletes out of millions of dollars.[82] Shamoil T. Shipchandler, Director of the SEC’s Fort Worth Regional Office stated, “[w]e allege that Narayan exploited athletes and other clients who trusted him to manage their finances. He fraudulently funneled their savings into a money-losing business and his own pocket.”[83]

Narayan is said to have gained the trust of athletes such as Mark Sanchez, Jake Peavy, and Roy Oswalt, only to funnel their investments into a failing business and his personal bank accounts.[84] During his alleged scheme, Narayan was employed by RGT Capital Management, Ltd.[85] As an advisor, Narayan had a fiduciary duty to his clients, which required him to make full disclosures of material fact and provide suitable investment advice to his clients.[86] Instead, Narayan put a large portion of his clients’ funds into The Ticket Reserve, an online ticketing business of which he was the chief fundraiser, a member of the board of directors, and owner of more than three million shares in the company.[87] Over a six-year period between 2010 and 2016, Narayan is accused of siphoning more than $33 million from his clients into the ticketing business.[88] At the time of the alleged scam, The Ticket Reserve was struggling, however, Narayan took $2 million in compensation for his “fundraising” efforts.[89]

Narayan’s former clients claim that he gained their trust through his emphasis on his religious faith, successful advising career, and falsely asserting that he was a certified public accountant.[90] All of the athletes involved stated that they were looking for consistent, conservative investments.[91] The SEC complaint alleges that “Narayan’s clients trusted and relied upon Narayan to pursue safe, conservative investments that would not put their principal at risk, realizing that as professional athletes with injury risks, their earnings might occur within a short window.”[92] Conversely, The Ticket Reserve was characterized as “very risky and inconsistent.”[93] Narayan failed to disclose other key conflicts of interest, including that he was a member of The Ticket Reserve’s board of directors and owned more than three million shares of company stock.[94] Additionally, Narayan ignored his former clients’ requests specifying their investment limits. For example, Oswalt agreed to invest $300,000 maximum in the company.[95] However, without Oswalt’s knowledge, Narayan took more than $7 million of his money to be placed in The Ticket Reserve.[96] Further, Sanchez agreed to a maximum $100,000 investment.[97] However, Narayan took $7 million instead and again placed that money into The Ticket Reserve.[98]

Narayan’s former clients claim that he gained their trust through his emphasis on his religious faith, successful advising career, and falsely asserting that he was a certified public accountant.[90] All of the athletes involved stated that they were looking for consistent, conservative investments.[91] The SEC complaint alleges that “Narayan’s clients trusted and relied upon Narayan to pursue safe, conservative investments that would not put their principal at risk, realizing that as professional athletes with injury risks, their earnings might occur within a short window.”[92] Conversely, The Ticket Reserve was characterized as “very risky and inconsistent.”[93] Narayan failed to disclose other key conflicts of interest, including that he was a member of The Ticket Reserve’s board of directors and owned more than three million shares of company stock.[94] Additionally, Narayan ignored his former clients’ requests specifying their investment limits. For example, Oswalt agreed to invest $300,000 maximum in the company.[95] However, without Oswalt’s knowledge, Narayan took more than $7 million of his money to be placed in The Ticket Reserve.[96] Further, Sanchez agreed to a maximum $100,000 investment.[97] However, Narayan took $7 million instead and again placed that money into The Ticket Reserve.[98]

According to the complaint filed on May 24, 2016, the SEC alleged five claims against Narayan, Richard Harmon, and John Kaptrosky.[99] The claims against all the defendants included violations of Section 10(b) of the Exchange Act [15 U.S.C. § 78j(b)] and Rules 10b-5(a) and (c) thereunder [17 C.F.R. § 240.10b-5].[100] The complaint specifies that:

According to the complaint filed on May 24, 2016, the SEC alleged five claims against Narayan, Richard Harmon, and John Kaptrosky.[99] The claims against all the defendants included violations of Section 10(b) of the Exchange Act [15 U.S.C. § 78j(b)] and Rules 10b-5(a) and (c) thereunder [17 C.F.R. § 240.10b-5].[100] The complaint specifies that:

Each Defendant, by engaging in the conduct described above, directly or indirectly singly or in concert with others, in connection with the purchase or sale of a security, by the use of means or instrumentalities of interstate commerce, or of the mails, or of the facilities of a national securities exchange, knowingly or recklessly: (a) employed a device, scheme, or artifice to defraud; and/or (b) engaged in an act, practice, or course of business which operated or would operate as a fraud or deceit upon a person.[101]

The complaint also alleges Violations Section 17(a)(1) and (3) of the Securities Act [15 U.S.C. § 77q(a)].[102]

Each Defendant, by engaging in the conduct above, singly or in concert with others, in the offer or sale of securities, by the use of means or instruments of transportation or communication in interstate commerce or by use of the mails, directly or indirectly: (a) knowingly or severely recklessly employed a device, scheme, or artifice to defraud; or (b) knowingly, recklessly, or negligently engaged in a transaction, practice, or course of business which operated or would operate as a fraud or deceit upon the purchaser.[103]

The SEC also alleged violations solely against Narayan. Specifically, the complaint alleged the same two claims and also included Violations of Section 206(1) and 206(2) of the Advisers Act [[15 U.S.C §§ 80b-6(1)-(2)]].[104]

On November 21, 2016, the United States District Court for the Northern District of Texas Dallas Division issued a Final Judgment regarding the SEC’s complaint against Narayan.[105] The Court ordered that Narayan

[s]hall pay a disgorgement of $1,498,000 and a civil penalty in the amount of $350,000 pursuant to Section 20(d) of the Securities Act [15 U.S.C. § 77t(d)] and Section 21(d) of the Exchange Act [15 U.S.C. § 78u(d)]. Defendant shall satisfy this obligation pursuant to the terms of the payment schedule set forth in paragraph V below after entry of this Final Judgment.[106]

The Court specified the terms of the payment in paragraph V:

Defendant shall pay the total of disgorgement and penalty due of $1,848,000 in installments to the Commission according to the following schedule: (1) $25,000, within 14 days of entry of this Final Judgment, payable from funds currently frozen under the Court’s prior orders in this case; (2) $100,000 within 1 year of the entry of this Final Judgment; and (3) the balance due within 2 years of the entry of this Final Judgment. Payments shall be deemed made on the date they are received by the Commission and shall be applied first to post judgment interest, which accrues pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1961 on any delinquent amounts. . . . If Defendant fails to make any payment by the date agreed and/or in the amount agreed according to the schedule set forth above, all outstanding payments under this Final Judgment, including post-judgment interest, minus any payments made, shall become due and payable immediately at the discretion of the staff of the commission without further application to the Court.[107]

IV. How Can Athletes Protect Themselves?

Despite the millions of dollars that top-tier professional athletes accumulate over their careers, lavish lifestyle choices merged with expensive entourages and inexperienced financial managers often lead to bankruptcy. One out of every six NFL players will file for bankruptcy during retirement.[108] Bankruptcy filings often begin as early as two years after retirement.[109] NFL stars or long-term players have the same risk of bankruptcy as any other NFL players.[110] On average, NBA players who declare bankruptcy will do so 7.3 years after retirement.[111] 6.1% of all NBA players will go bankrupt within 15 years of retirement.[112] Athletes that have filed for bankruptcy include: Kenny Anderson, Wally Backman, Charlie Batch, Bruse Berenyi, Riddick Bowe, Randy Brown, Mark Brunell, Bill Bucker, Jason Caffey, Dale Carter, Jack Clark, Raymond Clayborn, Derrick Coleman, Dermontti Dawson, Jim Dooley, Lenny Dykstra, Luther Elliss, Eddie Edwards, Chris Eubank, Rollie Fingers, Archie Griffin, Ray Guy, Tony Gwynn, Dorothy Hamill, Scott Harrison, Steve Howe, Harmon Killebrew, Bernie Kosar, Terry Long, Rick Mahorn, Harvey Martin, Deuce McAllister, Darren McCarthy, Denny McLain, Craig Morton, Greg Nettles, Jonny Neumann, Gaylord Perry, John Arne Riise, Andre Rison, Rumeal Robinson, Manny Sanguillen, Warren Sapp, Billy Sims, Leon Spinks, Sheryl Swoopes, Roscoe Tanner, Lawrence Taylor, Duane Thomas, Bryan Trottier, Mike Tyson, Johnny Unitas, Michael Vick, Antoine Walker, Danny White, Ray Williams, and Rick Wise, to name a few.[113] Sports Illustrated estimated that 80% of retired NFL players go broke in their first three years out of the League.[114] With the median income in the NFL being roughly $750,000 and the average career span less than four years, lack of competent financial planning, lack of long-term financial awareness, and lack of preparation for a second career all contribute to this issue.[115]

Mike Tyson and Evander Holyfield are prime examples of this phenomenon. The pair became the most successful boxers of their time, and made $390 million and $324 million respectively during their time in the ring.[116] Unfortunately, both eventually filed bankruptcy, with Tyson claiming to be $30 million in debt.[117]

Mike Tyson and Evander Holyfield are prime examples of this phenomenon. The pair became the most successful boxers of their time, and made $390 million and $324 million respectively during their time in the ring.[116] Unfortunately, both eventually filed bankruptcy, with Tyson claiming to be $30 million in debt.[117]

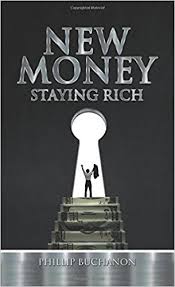

This is a reality for many athletes and is directly related to the exclusive trust that athletes put in others to handle their finances. Tim Duncan recognized this problem after he was a victim of a financial scam at the hand of a trusted advisor. Duncan stressed how important it is to employ a team of advisors and not to rely on one person.[118] “I thought, for the most part, I was keeping an eye on things. You have to keep people checking on people checking on people. I did that for a while. Obviously, I got to a point where the people I trusted were checking on themselves.”[119] Former NFL cornerback Phillip Buchanon recently published a book addressing this very issue, titled, “New Money: Staying Rich.”[120] In this financial tell all, Buchanon stresses how financial mismanagement, overspending, and business mistakes were often encouraged by the people closest to him.[121] His own mother even told him that he had to give her $1 million for all that she had done for him growing up.[122] Situations like this created money issues for Buchanan, and he wants to help fellow athletes to not make the same mistakes that he did.

Buchanon simplified his advice into four main takeaways, warning athletes about the risks and temptations that come with financial success. Buchanon stated that athletes need to: (1) “draw the line between wants and needs, (2) watch out for takers, (3) surround yourself with real friends and mentors, and (4) ask questions when getting financial advice.”[123] Suddenly earning a big paycheck and attending events with celebrities does not mean that you have an unlimited income, says Buchanon.[124] Buchanon went on to highlight that “once you get a lot of money, you automatically become a giver, and everyone else is a taker. You have to have a limit, because takers don’t have limits. They’ll keep asking you because they think you’ve got it.”[125] In Buchanon’s experience, many of the takers may even be as close as friends, family, and mentors. That is why surrounding yourself with people you can trust is crucial in preserving financial success. Buchanon states, “real friends help you make better decisions about your life, and mentors, who have gone through what you are experiencing, can help guide you when it comes to relationships, business, money and life.”[126] Further, just because someone is a financial adviser does not mean that they are trustworthy, says Buchanon.[127] It is crucial that when an athlete hires a financial advisor that they fully understand the advisor’s motivations and understand that they may not always be thinking exclusively about the athlete’s best interests.

Buchanon simplified his advice into four main takeaways, warning athletes about the risks and temptations that come with financial success. Buchanon stated that athletes need to: (1) “draw the line between wants and needs, (2) watch out for takers, (3) surround yourself with real friends and mentors, and (4) ask questions when getting financial advice.”[123] Suddenly earning a big paycheck and attending events with celebrities does not mean that you have an unlimited income, says Buchanon.[124] Buchanon went on to highlight that “once you get a lot of money, you automatically become a giver, and everyone else is a taker. You have to have a limit, because takers don’t have limits. They’ll keep asking you because they think you’ve got it.”[125] In Buchanon’s experience, many of the takers may even be as close as friends, family, and mentors. That is why surrounding yourself with people you can trust is crucial in preserving financial success. Buchanon states, “real friends help you make better decisions about your life, and mentors, who have gone through what you are experiencing, can help guide you when it comes to relationships, business, money and life.”[126] Further, just because someone is a financial adviser does not mean that they are trustworthy, says Buchanon.[127] It is crucial that when an athlete hires a financial advisor that they fully understand the advisor’s motivations and understand that they may not always be thinking exclusively about the athlete’s best interests.

As a last resort, when athletes are taken advantage of by financial advisors, there are common law remedies that can be brought against the advisors for alleged misdealings. For example, Clinton Portis filed his own lawsuit against the law firm of Greenberg Traurig and Attorney Pamela Linden with respect to a bankrupt Alabama Casino Project.[128] Portis alleged state law claims including Negligence and Breach of Fiduciary Duty.[129] Another example is Darrelle Revis, who alleged causes of action against former agents Neil Scwartz and Jonathon Feinsod.[130] Revis accused the pair of funneling funds from Revis’ endorsement checks to separate attorneys and alleged fraud, conversion, breach of fiduciary duty, and theft.[131]

As a last resort, when athletes are taken advantage of by financial advisors, there are common law remedies that can be brought against the advisors for alleged misdealings. For example, Clinton Portis filed his own lawsuit against the law firm of Greenberg Traurig and Attorney Pamela Linden with respect to a bankrupt Alabama Casino Project.[128] Portis alleged state law claims including Negligence and Breach of Fiduciary Duty.[129] Another example is Darrelle Revis, who alleged causes of action against former agents Neil Scwartz and Jonathon Feinsod.[130] Revis accused the pair of funneling funds from Revis’ endorsement checks to separate attorneys and alleged fraud, conversion, breach of fiduciary duty, and theft.[131]

V. Who is Qualified To Be A Financial Manager?

Buchanon’s advice to players begs the obvious question that is often overlooked: who is qualified to be an athlete’s financial advisor? In the United States, there are more than 270,000 financial advisors.[132] Although generally all financial advisors are at least familiar with traditional investing, a large majority do not specialize in athlete management, and are not equipped to handle the large sums of money and unique circumstances that are central to the sports industry.[133] For instance, the average financial advisor handles clients age 63, with an average account size of $425,944, with the primary service specifically focused on retirement planning.[134] In contrast, the age range of a professional athlete is 18 to 35 years old, with uneven cash flow, job insecurity, large egos, and a plethora of other complexities that are unique to being a professional athlete.[135]

At the very least, it is essential that any capable financial advisor be licensed with either a Series 65 license or a combination of the Series 7 license and Series 66 License.[136] Further, every financial advisor should hold at least one designation of Certified Financial Planner (CFP), Certified Public Accountant (CPA), or Chartered Financial Analyst (CFA).[137]

Addressing each in turn, only 17% of all financial advisors are CFP’s.[138] CFP’s are credentialed experts in financial planning, estate planning, insurance, investments, taxes, employee benefits, and retirement planning.[139] CPA’s who specialize in working with athletes are extremely effective when it comes to tax planning.[140] This is an area that is often overlooked, however, when dealing with an inordinate sum of money, tax implications are crucial to financial success.[141] Finally, the most elite designation is a CFA. Prerequisites for this designation include four years of qualified work experience and completion of the CFA Program (passing three six-hour examinations), which takes approximately four years to complete.[142]

Some leagues choose to set their own qualifications for financial advisors. In the NFL, for example, there are certain eligibility requirements to be licensed as an NFLPA financial advisor. The requirements include but are not limited to the following: (1) bachelor’s degree from an accredited university; (2) minimum eight years of licensed experience (qualifying licenses include FINRA series licenses, Attorney, CPA or an insurance license); (3) minimum of $4 million of insurance coverage, through professional liability, errors and omissions or a fidelity bond; (4) no civil, criminal, or regulatory history related to fraud; (5) no pending customer complaints or litigation at the time of the application; (6) must not maintain custody of player funds unless deemed a qualified custodian.[143] This list suggests that although the NFLPA has established criteria to vet potential financial advisors, the requirements are generally not hard to meet, and the program itself may be inherently flawed.[144]

Some leagues choose to set their own qualifications for financial advisors. In the NFL, for example, there are certain eligibility requirements to be licensed as an NFLPA financial advisor. The requirements include but are not limited to the following: (1) bachelor’s degree from an accredited university; (2) minimum eight years of licensed experience (qualifying licenses include FINRA series licenses, Attorney, CPA or an insurance license); (3) minimum of $4 million of insurance coverage, through professional liability, errors and omissions or a fidelity bond; (4) no civil, criminal, or regulatory history related to fraud; (5) no pending customer complaints or litigation at the time of the application; (6) must not maintain custody of player funds unless deemed a qualified custodian.[143] This list suggests that although the NFLPA has established criteria to vet potential financial advisors, the requirements are generally not hard to meet, and the program itself may be inherently flawed.[144]

The NFLPA advises players to only use financial advisors that are registered and meet the above criteria.[145] Memos from the NFLPA were also sent to agents instructing them to only recommend registered NFLPA financial advisors to their clients.[146] Matt Birk, a fifteen year NFL veteran and Harvard graduate expressed his support of the program: “[w]hen I’m told by the (NFLPA) that here’s a list of registered financial guys, I take that to mean that they’re OK, that the (union) has done its due diligence.”[147] He went on to state, “[t]hat’s not to say everything is perfect with the guys on the list. There are no guarantees that you’re actually going to make money. But you don’t expect guys on that list are going to lead you into a scheme.”[148]

Agents around the NFL disagree with Birk, and cite to past misdealings by certified NFLPA financial advisors to back their opinions. One NFL agent stated, “[t]he program is ridiculous. Think about it, based on what the NFLPA is doing, I couldn’t recommend Warren Buffet. Instead, we’re supposed to tell a player only use someone from this list the union puts out. I’m not taking the potential liability.”[149]

Agents around the NFL disagree with Birk, and cite to past misdealings by certified NFLPA financial advisors to back their opinions. One NFL agent stated, “[t]he program is ridiculous. Think about it, based on what the NFLPA is doing, I couldn’t recommend Warren Buffet. Instead, we’re supposed to tell a player only use someone from this list the union puts out. I’m not taking the potential liability.”[149]

The criticisms of the program are all centered on the notion that simply being registered as an NFLPA financial advisor does not necessarily qualify these individuals to handle large sums of money.[150] Yet players see the list and assume that every name on the page is a highly qualified and skilled advisor in the field.[151] One agent stated that he sees players getting taken advantage of in ways that often never reach a news story or become a headline.[152]

It’s not even just stealing, which eventually happens with some of them. It’s the fees some of these guys charge. A player is ‘investing’ $50,000, but then he doesn’t see all the handling fees and charges that the advisor charges on top. Or a big one is bill pay. I see players getting charged $2,000 a month for services they don’t even need. These guys have about four bills a month they don’t want to take the time to learn how to do it.[153]

VI. Legal Causes of Action for Financial Mismanagement

Athletes are prime targets for financial exploitation, and it is critical that players are aware of the legal causes of action available to them if a legal remedy is necessary. First are the Federal Securities Laws. These laws include anti-fraud provisions which contain private rights of action for defrauded investors.[154] These laws are available to protect against any scheme by a broker to defraud or make untrue statements meant to deceive investors, including unsuitable trading, insider trading, stock manipulation, churning and unauthorized trading.[155] Specifically, securities civil claims that can affect corporations, LLCs, limited partnerships, and their principal figures are fraud claims under Section 10(b) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, fraud claims involving inadequate control of accounting practices, SEC charges of fraud in financial reporting, insider trading claims under Section 17(a) of Securities Act of 1933, claims seeking injunctive relief to halt proxy votes under Section 14 of the Exchange Act, SEC fraud actions under the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act of 1977, “derivative” actions alleging breach of fiduciary duty and other wrongs, and claims under various state’s “blue-sky” laws.[156]

Many state securities laws (“blue sky” laws), contain anti-fraud provisions which include private rights of action.[157] However, certain states do not include a private right of action under their blue-sky laws.[158] Thus, athletes in those states should rely on the federal and common law causes of action.

Fraud and misrepresentation are claims that are satisfied when there is a “false representation of a material fact with knowledge of the falsity for the purpose of inducing the investor to act, and that the investor relied upon the representation as true and acted upon it to his detriment.”[159] “Mere omission” will constitute fraud if the financial manager had a duty to disclose the fact omitted.[160] If a financial manager were to recommend that an athlete pursue an investment without disclosing the risks, that would constitute a fraudulent misrepresentation.[161]

Negligence and malpractice are another set of claims that athletes may assert. These claims are based on the duty owed by a financial manager to the athlete and the breach of that duty.[162] Even if a financial manager did not knowingly make false statements to the athlete, he or she may be subject to negligent misrepresentations liability.[163] Further, failing to properly diversify a portfolio may subject a financial manager to a negligent management claim.[164] Financial management firms may also be held liable for negligent supervision if they fail to implement or enforce supervisory and compliance procedures.[165]

Negligence and malpractice are another set of claims that athletes may assert. These claims are based on the duty owed by a financial manager to the athlete and the breach of that duty.[162] Even if a financial manager did not knowingly make false statements to the athlete, he or she may be subject to negligent misrepresentations liability.[163] Further, failing to properly diversify a portfolio may subject a financial manager to a negligent management claim.[164] Financial management firms may also be held liable for negligent supervision if they fail to implement or enforce supervisory and compliance procedures.[165]

In some instances, an athlete may also be able to bring a breach of contract claim against their financial manager. These claims are based upon the contract that the athlete signs with the financial manager or firm.[166] Claims may be asserted if the firm fails to follow the athlete’s instructions, mismanages of an account, or engages in a breach of the implied covenant of good faith.[167]

Breach of fiduciary duty is another legal cause of action that victims of financial mismanagement may assert. A breach of fiduciary duty applies when there is a relationship of trust and reliance between the athlete and financial manager.[168] The fiduciary is obligated to act in a diligent and faithful manner to further the client’s best interest, and must conduct themselves with good faith and integrity.[169]

Breach of fiduciary duty is another legal cause of action that victims of financial mismanagement may assert. A breach of fiduciary duty applies when there is a relationship of trust and reliance between the athlete and financial manager.[168] The fiduciary is obligated to act in a diligent and faithful manner to further the client’s best interest, and must conduct themselves with good faith and integrity.[169]

Unjust enrichment is a claim that is valid when there is no governing contract. Under this claim, an athlete must allege that “the defendant was enriched at the plaintiff’s expense and that the circumstances are such that equity and good conscience require that the defendant make restitution.”[170] Similarly, promissory estoppel may be asserted when there is no contract governing the action.[171]

Conversion is the wrongful or unauthorized exercise of dominion or control over chattel.[172] Courts have held that an agent who failed to account for the principal’s funds was liable for conversion.[173]

VII. Financial Literacy and Player Education

In hopes of reversing the current statistics showing that 80% of NFL players and 60% of NBA players will be broke within five years after leaving their respective leagues, The Global Sports and Entertainment Division of Morgan Stanley (Morgan Stanley) is attempting to help.[174] Morgan Stanley put together a team of 80 financial advisers to teach wealth management to college and professional athletes who are willing to learn from these experts.[175] In order to make the advice more practical, the team brought in Antoine Walker to talk about his poor decisions and financial mismanagement.[176] Walker made over $108 million during his 13-year career in the NBA, yet in his first year after retirement he filed for bankruptcy, claiming $4.3 million in assets to his $12.7 million in debts.[177] Although the group understands that they cannot advise everyone, Morgan Stanley estimated that they worked with 2,600 student athletes in one year, as well as professionals from NFL teams that include the Jacksonville Jaguars, Pittsburgh Steelers, and Seattle Seahawks.[178]

While Morgan Stanley has developed its own group of educators, leagues and teams have also identified the issue of financial management in the industry, and are trying their best to educate players. Wesley Edens, co-owner of the Milwaukee Bucks, has been giving his players financial advice to help them avoid financial mismanagement.[179] During the first summer after he and Marc Lasry purchased the team, Edens held voluntary private presentations with players at his home in order to discuss how players can manage their funds in order to promote stability and financial growth.[180] Edens recognized that some of the players on the team are still teenagers, and stated: “I want to help guys out to understand financially how to be in a better place. I know when I was 22 years old, I made a lot of bad decisions.”[181]

While Morgan Stanley has developed its own group of educators, leagues and teams have also identified the issue of financial management in the industry, and are trying their best to educate players. Wesley Edens, co-owner of the Milwaukee Bucks, has been giving his players financial advice to help them avoid financial mismanagement.[179] During the first summer after he and Marc Lasry purchased the team, Edens held voluntary private presentations with players at his home in order to discuss how players can manage their funds in order to promote stability and financial growth.[180] Edens recognized that some of the players on the team are still teenagers, and stated: “I want to help guys out to understand financially how to be in a better place. I know when I was 22 years old, I made a lot of bad decisions.”[181]

The NFL provides players with financial knowledge through the National Football League Financial Education Program (FEP).[182] In order to ensure financial stability for players, the program offers resources and realistic perspective though non-credit seminars that teach players about cash management, insurance, tax planning, estate planning, investments, retirement planning, and other related topics.[183] The NFL also partners with the FINRA Investor Education Foundation in order to give players a resource if they have questions about investing or investment products.[184] Further, along with financial simulations and credit management training, the NFL has partnered with the NFLPA and schools of business to bring players the Business Management & Entrepreneurial Program.[185] The program consists of workshops, business discussions, and lectures that are customized to improve players’ business acumen in order to build practical knowledge for players interested in owning, operating, or developing their own businesses.[186]

The NFL is not alone in the financial education of athletes. In 1991, the MLB partnered with the MLB Players Association and launched the Rookie Career Development Program.[187] The program is an annual symposium, featuring three to four young MLB stars, that focuses on teaching young players to focus on things that might not be obvious to someone that is not used to making a significant amount of money.[188]

The NFL is not alone in the financial education of athletes. In 1991, the MLB partnered with the MLB Players Association and launched the Rookie Career Development Program.[187] The program is an annual symposium, featuring three to four young MLB stars, that focuses on teaching young players to focus on things that might not be obvious to someone that is not used to making a significant amount of money.[188]

While education from the leagues is excellent, it is also critical that colleges and universities begin to educate their undergraduate athletes on personal finances in order to prepare them for the professional level. Universities have started using on-campus speakers and workshops in order to engage student athletes in the financial content.[189]

For example, Arizona State University Professor Glenn Wong introduced a personal finance, business, and law hybrid course designed to teach student-athletes about potential future legal and business issues.[190] The NCAA offers financial awareness best practices and a list of useful finance resources for student-athletes.[191] Game Plan announced a partnership with Wells Fargo to deliver its Hands on Banking financial literacy program to over 40 athletic departments through Game Plan’s student-athlete development platform.[192] These modules include everything from financial basics to advanced content like best practices for investing, job search and interviewing, and building credit.[193]

For example, Arizona State University Professor Glenn Wong introduced a personal finance, business, and law hybrid course designed to teach student-athletes about potential future legal and business issues.[190] The NCAA offers financial awareness best practices and a list of useful finance resources for student-athletes.[191] Game Plan announced a partnership with Wells Fargo to deliver its Hands on Banking financial literacy program to over 40 athletic departments through Game Plan’s student-athlete development platform.[192] These modules include everything from financial basics to advanced content like best practices for investing, job search and interviewing, and building credit.[193]

All states should require a course in high school that cover personal financial education. In Wisconsin in 2017, Governor Scott Walker “signed into law legislation [. . .] that requires public school boards in the state to adopt academic standards for financial literacy and incorporate instruction in personal finance into the curriculum from kindergarten through high school.”[194] The legislation had bipartisan support along with support from most of the industries that handle personal finances.[195] “‘Financial education is an important aspect of every person’s life,’ said Rose Oswald Poels, president and chief executive of the Wisconsin Bankers Association.”[196]

VIII. Athlete Success Stories

Staggering statistics show that two years after retirement, 78% of former NFL players were bankrupt or in financial stress.[197] In the NBA, an estimated 60% of former players have gone broke.[198] While these statistics are proof that a lot can go wrong for athletes at the hands of financial mismanagement, there is also a lot that can go right. “The people who manage things well don’t exclusively rely on other people to do everything for them,” says David Kenny, partner at the accounting and business advisory firm Hall Chadwick.”[199] Kenny goes on to say: “[y]ou hear, ‘[m]y manager can do that’ a lot, but they (professional athletes) are not going to have a personal concierge after sport. They need to know how to do basic things like pay bills or to have a mortgage [and] learn to be self-sufficient.”[200]

A prime example of how athletes can maintain and expand financial success once they stop competing on the field or on the court is seen in former NBA star Michael Jordan. Jordan has invested in business interests that are worth a reported $1.45 billion.[201] Although Jordan’s use of his name and endorsements is probably the exception rather than the rule, it is a prime example of how athletic success can translate into financial success of the court.

A prime example of how athletes can maintain and expand financial success once they stop competing on the field or on the court is seen in former NBA star Michael Jordan. Jordan has invested in business interests that are worth a reported $1.45 billion.[201] Although Jordan’s use of his name and endorsements is probably the exception rather than the rule, it is a prime example of how athletic success can translate into financial success of the court.

Another example of a financial all-star is former Heisman Trophy winner and NFL defensive player of the year Charles Woodson. Woodson owns and develops real estate, has his own clothing line, and even owns his own wine brand.[202] Woodson surrounded himself with ethical and competent people, and in doing so, became smart in the ways of investing his NFL career earnings.[203]

Another example of a financial all-star is former Heisman Trophy winner and NFL defensive player of the year Charles Woodson. Woodson owns and develops real estate, has his own clothing line, and even owns his own wine brand.[202] Woodson surrounded himself with ethical and competent people, and in doing so, became smart in the ways of investing his NFL career earnings.[203]

Earvin “Magic” Johnson has followed Jordan’s success and has a personal worth of an estimated $657 million.[204] For Johnson, one key to success is the fact that he did not wait until after he finished his playing career to investigate business opportunities.[205] Before his retirement from the NBA, Johnson spoke with business leaders and executives in different states in order to pinpoint the most successful investments for when he retired.[206] Johnson took this knowledge and executed savvy business investments in Starbucks and the Los Angeles Lakers, among other business ventures, to build his financial worth.[207]

Earvin “Magic” Johnson has followed Jordan’s success and has a personal worth of an estimated $657 million.[204] For Johnson, one key to success is the fact that he did not wait until after he finished his playing career to investigate business opportunities.[205] Before his retirement from the NBA, Johnson spoke with business leaders and executives in different states in order to pinpoint the most successful investments for when he retired.[206] Johnson took this knowledge and executed savvy business investments in Starbucks and the Los Angeles Lakers, among other business ventures, to build his financial worth.[207]

Serena and Venus Williams also top the list of successful athlete investors and financial managers. Venus Williams is the CEO of V Starr Interiors, part owner of the Miami Dolphins in the NFL, franchise owner of Jamba Juice, and manages an athletic clothing line.[208] Not to be outdone by Venus’ off-court success, Serena also owns a portion of the Dolphins, manages her own fashion label, and maintains endorsements with Chase Bank and PepsiCo.[209] The sisters’ financial success should not be outshined by their athletic success. While managing these successful investments, Venus and Serena are currently ranked ninth and fifteenth respectively in the WTA Tour Rankings.[210]

Serena and Venus Williams also top the list of successful athlete investors and financial managers. Venus Williams is the CEO of V Starr Interiors, part owner of the Miami Dolphins in the NFL, franchise owner of Jamba Juice, and manages an athletic clothing line.[208] Not to be outdone by Venus’ off-court success, Serena also owns a portion of the Dolphins, manages her own fashion label, and maintains endorsements with Chase Bank and PepsiCo.[209] The sisters’ financial success should not be outshined by their athletic success. While managing these successful investments, Venus and Serena are currently ranked ninth and fifteenth respectively in the WTA Tour Rankings.[210]

Other current athletes are following in the Williams sisters’ footsteps and are taking strides to set themselves up for financial success prior to retirement in sport. Former NBA number one draft pick Andrew Bogut (Bogut) said that he decided to educate himself for financial success after basketball.[211] Bogut stated:

I did a full year’s course on financial planning and financial management, which covered everything from budgeting to going through different investment criteria – stocks, bonds, and all that type of stuff. It really helped me. It gives you a little bit more than the basics, where you can manage yourself, and [you can] save that 30, 40, or 50 grand you’re paying someone to do this stuff for you.[212]

IX. Conclusion

The amount of money that athletes earn should make them financially stable and comfortable for the rest of their lives. Unfortunately, based on the statistics, this is not always the case. Due to short earning potentials, lavish lifestyles, and overly generous spending, the money that is made often fails to last for their lifetimes. As a result, athletes need to value the advice of former players, current financial advisors, and asset management specialists in order to avoid becoming a statistic of a financial disaster.

Athletes need to be cognizant of the “keeping up with the Joneses” mentality.[213] Peer competition among athletes contributes to this mentality, and many athletes try to one-up teammates and friends by overspending on luxury items.[214] Instead, athletes should learn to live comfortably, but sustainably, while living within his or her means.[215] Although genuine, often an athlete’s desire to financially support family and friends causes more harm than good. It is often best to establish support for family members to create their own wealth and success, rather than through lump sum funding.[216] Athletes need to be extremely careful of family overspending, as these gifts normally turn into ongoing financial obligations for the athlete.[217] Instead of offering total financial support, an alternative for an athlete is to pay for someone’s tuition or job-training, which will enable the person to develop skills in order to obtain employment and support themselves.[218]