By Martin J. Greenberg & Michael R. Gavin

I. Introduction

Sports facilities can generate substantial economic growth for their local communities.[1] Over the past decade, the sports industry has looked for ways to finance the construction or renovation of sports facilities during inconsistent economic environments, where at times real estate investments were riskier and municipal bond financing shifted towards other necessary local projects rather than sports facilities.[2] One significant response to this issue is the public-private partnership (P3).[3] P3s are “agreements formed between a public agency and a private-sector entity that allow for greater private sector participation in the delivery and financing of construction projects.”[4] There are several kinds of P3 structures with varying degrees of responsibilities between the public and a private entity.[5] Depending on how a P3 is executed, a local community can enhance themselves with a new sports facility.[6]

Beginning in 2018, a new form of private-sector investment into sports facilities came into existence with the passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA).[7] The TCJA, which amended the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, contains unique investment provisions that can add infrastructure and bolster the local economy of a low-income community.[8] Those particular provisions make up Opportunity Zones, which are codified under Section 1400Z of the Internal Revenue Code.[9] An Opportunity Zone “is an economically-distressed community where new investments, under certain conditions, may be eligible for preferential tax treatment.”[10] The preferential tax treatment allows an investor, based on how long he or she holds their investment in the Opportunity Zone, to defer and reduce the capital gains they used to invest into the Opportunity Zone, and either reduce or eliminate gains derived from their investment in Opportunity Zones whenever it is sold.[11] These tax incentives can alter P3s by either reducing public investment or eliminating public investment entirely.

Beginning in 2018, a new form of private-sector investment into sports facilities came into existence with the passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA).[7] The TCJA, which amended the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, contains unique investment provisions that can add infrastructure and bolster the local economy of a low-income community.[8] Those particular provisions make up Opportunity Zones, which are codified under Section 1400Z of the Internal Revenue Code.[9] An Opportunity Zone “is an economically-distressed community where new investments, under certain conditions, may be eligible for preferential tax treatment.”[10] The preferential tax treatment allows an investor, based on how long he or she holds their investment in the Opportunity Zone, to defer and reduce the capital gains they used to invest into the Opportunity Zone, and either reduce or eliminate gains derived from their investment in Opportunity Zones whenever it is sold.[11] These tax incentives can alter P3s by either reducing public investment or eliminating public investment entirely.

The purpose of this article is to examine how the use of Opportunity Zones can facilitate new investment into sports facilities and spur economic development. Part II of this article will provide a brief overview of P3s, including its role in stadium financing and methods. Next, Part III of this article will dive into Opportunity Zones, which will feature its legislative origins, a statutory analysis, notable information and tax filing requirements, and example tax calculations. Part IV will examine Opportunity Zones’ impact on local communities and the sports industry. Also, this article will provide examples of Opportunity Zones based on currently available information. Finally, Part V will conclude the article by offering closing observations and how the development of Opportunity Zones will impact investments into sports facilities going forward.

The purpose of this article is to examine how the use of Opportunity Zones can facilitate new investment into sports facilities and spur economic development. Part II of this article will provide a brief overview of P3s, including its role in stadium financing and methods. Next, Part III of this article will dive into Opportunity Zones, which will feature its legislative origins, a statutory analysis, notable information and tax filing requirements, and example tax calculations. Part IV will examine Opportunity Zones’ impact on local communities and the sports industry. Also, this article will provide examples of Opportunity Zones based on currently available information. Finally, Part V will conclude the article by offering closing observations and how the development of Opportunity Zones will impact investments into sports facilities going forward.

II. Public Private Partnerships (P3s)

A. P3s Generally

As previously stated, P3s are contractual agreements between a governmental entity

and a private entity that determines each party’s participation in financing the construction or renovation of facilities or infrastructure projects, and in our case, sports facilities.[12] A government’s ability to create P3s originates from either legislation or the government’s home rule power.[13] As for financing, the majority of P3 structures contain long-term financing arrangements.[14] Financing for P3s consists of acquiring the necessary upfront capital “to pay for the design and construction” of a P3 project.[15] There are two forms of financing P3 projects: debt and equity.[16] Debt is borrowed money from third parties, such as banks and other financial institutions.[17] On the other hand, equity is where third parties, such as contractors and investors, make a capital investment into a project in exchange for an ownership interest or management control.[18] What follows is a discussion of common forms of public and private financing of sports facilities.

i. Public Funding of Sports Facilities

a. Bonds

A government entity can invest in capital projects, such as sports facilities, through long-term monetary borrowing.[19] For governments, issuing bonds is the most common method of generating needed sports facility funding.[20] Bonds are government issued, interest-bearing certificates where the government promises to repay the principal amount of the bond plus interest at a specific future date.[21] The most well-known bond with respect to sports facility financing is municipal bonds.[22] Municipal bonds are debt securities issued by state and local governments to finance its capital expenditure projects.[23] Municipal bonds are extremely attractive because the interest income derived from the municipal bonds is exempt from federal income taxation, and quite possibly state and local income taxation as well.[24] Other bond mechanisms such as tax-increment bonds and special authority bonds can be used for the public funding of a sports facility.[25] Tax-increment bonds are bonds that are issued by a local government in order to invest in public infrastructure projects.[26] These bonds are backed by a percentage of projected future tax revenues from properties that are increasing in value.[27] Meanwhile, special authority bonds are financial instruments that are used by special public authorities who have public powers (e.g., turnpike and power authorities), but operate outside of normal governmental constraints.[28] These special authority bonds circumvent public resistance against sports facility projects, and enable the facility to be constructed without receiving public consent.[29]

b. Taxes and Tax Abatement

In addition to selling bonds and accumulating debt, the general public can fund sports facilities through various taxation methods.[30] Taxes allow a local government to generate revenue, which can be used to pay for a sports facility’s construction rather than incurring more debt.[31] There are generally two kinds of taxes that local governments levy to help pay for a sports facility’s construction costs: (1) hard taxes and (2) soft taxes.[32] Hard taxes consist of “taxes on local income, real estate, personal property, and general sales. These taxes often require voter approval[] because the burden of payment falls directly on the public’s shoulders.”[33] On the other hand, soft taxes include taxes imposed on car rentals, hotels, and restaurants among others.[34] In essence, these are participation taxes, in which consumers are paying taxes when they use or consume services. Outlined below are several examples of both hard taxes and soft taxes.

Hard Taxes[35]

| Type of Tax | Description |

| Local Income Tax | A tax levied on an individual in relation to their income, which can be from 0.5 to 2 percent. |

| Real Estate Tax | Taxes assessed on the value of land plus improvements made to the land, such as buildings or infrastructure. Generally, real estate taxes are reassessed every three to five years. |

| Personal Property Tax | A tax on tangible or intangible personal property. Tangible personal property includes items such as furniture, jewelry, and artwork while intangible personal property consists of items like insurance, stocks, and bonds. |

| General Sales Tax | A tax imposed by the government on the consumption of goods and services. Often times, this is a state or local government’s largest revenue source. A voter referendum is required since residents bear the tax burden. |

Soft Taxes[36]

| Type of Tax | Description |

| Car Rental Tax | A tax imposed on tourists who rent a vehicle. The average tax rate is about eight percent, and this tax is a popular method to finance sports facilities. |

| Taxi Tax | A tax that is incorporated into the rider’s final taxi fare, which can range from two to five percent. |

| Hotel/Motel and Restaurant Tax | A tax often imposed by local governments, these taxes range from six to fifteen percent and is factored into a customer’s final bill. Two to five percent of this tax is used to pay for any bonds that were issued to finance stadium construction. |

| Sin Tax | Also called an excise tax, sin taxes are imposed on alcohol and tobacco sales and gambling among others. |

| Player (Jock) Tax | A tax imposed by the State on a nonresident athlete’s income, who performs services within the State’s boundaries. |

Finally, a local government can issue tax abatements to spur private investment for the development of sports facilities.[37] Specifically, the government will exempt a private entity’s assets from property taxation for a period of time.[38] The property tax abatement can either be a full or partial abatement, and the time period of the exemption is subject to state law.[39] By issuing tax abatements, the government also hopes to create new employment opportunities.[40] The abatements are often issued on an as-needed basis as requested by the government, particularly in the negotiation cycle of offering an incentive package for a franchise to construct their stadium in the locality.[41]

ii. Private Funding of Sports Facilities

In addition to public funding, which can come in the form of municipal bonds and various forms of taxation, a sports facility can be funded by private investment in whole or in part.[42] Public funding generally involves the local government incurring debt and levying taxes, private funding can come in many different forms.[43] For example, external stakeholders can invest into sports facilities in exchange for an equity stake into the facility that hopefully results in a desirable return on investment.[44] Pledging generated revenues is another source for private funding of sports facilities, which includes naming rights, concessions, and ticket revenue.[45] Furthermore, a private entity can become a lender and issue debt to the team desiring to construct a sports facility.[46]

Taxpayers prefer private investment for sports facilities in order to save taxpayer dollars for other uses.[47] Private financing of a sports facility can take on many forms.[48] Generally, a private party contributes the debt or equity to finance the project, and the local government may contribute by providing property tax abatements and possible infrastructure improvements.[49] Typically, teams are given management control, in which they are responsible for the day-to-day operations such as hiring all pertinent staff, acquiring and maintaining sufficient insurance, and performing maintenance work when needed.[50] And with managing the facility, the teams enjoy retaining nearly all of the revenue derived from the facility’s operations.[51] Listed below are some common forms of private financing for a sports facility:

- Cash and in-kind contributions: donation of cash and/or goods and services, such as landscaping and fencing.[52]

- Naming rights: an agreement between parties where a sponsor pays a specified sum of money to secure their name or logo on a sports facility.[53]

- Concessionaire rights: rights transferred to a concessionaire for selling and dispending goods such as food, beverages, merchandise, souvenirs, and publications pursuant to a concession agreement.[54]

- Sponsorship packages: an arrangement where a sponsor obtains the right to display its name or logo on items such as uniforms and in-arena promotions.[55]

- Lease agreements: contracts between a lessor and lessee where the lessee pays a sum of money for use of the sports facility.[56]

- Luxury suites: A suite that is leased to a lessee and their guests for a specified period of time.[57]

- Premium seating (club seats): sections of individual seating that contain enhanced amenities, such as a wait staff and more comfortable seats.[58]

- Personal seat licenses: “fees paid by individuals to guarantee the individual a right to purchase season tickets in a specified location for a designated period of time.”[59]

- Parking facility fees: revenues derived from fans parking at or near a sports facility.[60]

- Merchandise revenues: revenues generated from the sale of team merchandise.[61]

- Advertising: revenues derived from various mediums, including in-arena signage and television.[62]

- Vendor/contractor equity: vendors or other outside parties provide goods or services for an equity stake in the facility.[63]

III. Opportunity Zones

The P3 model for sports facility financing was shaken up starting in 2018 with the

birth of Opportunity Zones. As discussed below, Opportunity Zones can be used as an additional private funding source for a sports facility or district, and can change the equation of a P3 that tilts towards more private funding. This section will dive into a discussion of Opportunity Zones’ origin, a statutory analysis and application, its impact on local communities and the sports industry, and a select listing of current Opportunity Zones in the sports industry.

A. Origin & Policy

On December 22, 2017, President Donald Trump signed into law the largest reformation

of the United State tax code in recent history known as the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA).[64] Texas Republican Representative Kevin Brady sponsored the legislation and the TCJA only took about seven weeks from its introduction in the House of Representatives until it became law.[65] Among its notable accomplishments, the TCJA reduces the income tax rates among all individuals anywhere from one to four percent depending on a taxpayer’s tax bracket.[66] Perhaps more significantly, the TCJA reduced the corporate tax rate from as high as 35 percent to 21 percent.[67] However, there is one aspect of the TCJA that is exponentially significant which is the focus of this article: Opportunity Zones.

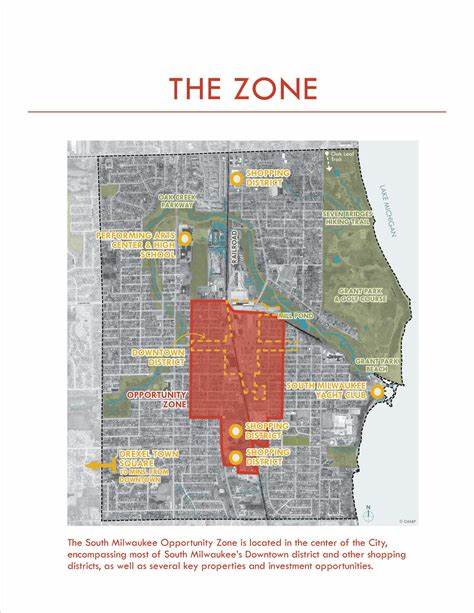

As alluded to earlier, Opportunity Zones are economically-distressed communities which offer an investor preferential tax treatment in exchange for an investment in an Opportunity Zone. The policy objective of Opportunity Zones is to enable the private sector to invest in low income communities to spur economic development nationwide.[68] In simplistic terms, Opportunity Zones are tracts of land nominated by the governor of a state to the United States Treasury Department for Opportunity Zone certification.[69] This certification will allow private investors to invest in the Opportunity Zone and become eligible for the favorable tax treatment.[70] According to the Economic Innovation Group, there are over 8,700 Opportunity Zones in the United States and its territories.[71]

As alluded to earlier, Opportunity Zones are economically-distressed communities which offer an investor preferential tax treatment in exchange for an investment in an Opportunity Zone. The policy objective of Opportunity Zones is to enable the private sector to invest in low income communities to spur economic development nationwide.[68] In simplistic terms, Opportunity Zones are tracts of land nominated by the governor of a state to the United States Treasury Department for Opportunity Zone certification.[69] This certification will allow private investors to invest in the Opportunity Zone and become eligible for the favorable tax treatment.[70] According to the Economic Innovation Group, there are over 8,700 Opportunity Zones in the United States and its territories.[71]

The TCJA’s Opportunity Zones provisions are based on the 2015 Investing in Opportunity Act, which had bipartisan support from members of both the United States House of Representatives and the Senate.[72] Despite receiving bipartisan support, this Bill did not advance past its introduction in the Senate by Republican South Carolina Senator Tim Scott.[73] However, just two years later under the TCJA, Opportunity Zones became a reality. The legislative intent for Opportunity Zones was to transform low-income communities in a positive way, “including new jobs and higher wages.”[74] As noted in a letter from several United States Senators, including Senator Scott, to then-Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin, the Senators expressed that some of these communities hoping for a transformation were among those that did not recover after the Great Recession.[75] Additionally, the Senators explained that the Opportunity Zone provisions were made to incentivize investment in rural and urban communities, offer flexibility by encouraging investment, and to enable the risks and costs of the investment borne by private investors through a fund structure.[76]

The TCJA’s Opportunity Zones provisions are based on the 2015 Investing in Opportunity Act, which had bipartisan support from members of both the United States House of Representatives and the Senate.[72] Despite receiving bipartisan support, this Bill did not advance past its introduction in the Senate by Republican South Carolina Senator Tim Scott.[73] However, just two years later under the TCJA, Opportunity Zones became a reality. The legislative intent for Opportunity Zones was to transform low-income communities in a positive way, “including new jobs and higher wages.”[74] As noted in a letter from several United States Senators, including Senator Scott, to then-Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin, the Senators expressed that some of these communities hoping for a transformation were among those that did not recover after the Great Recession.[75] Additionally, the Senators explained that the Opportunity Zone provisions were made to incentivize investment in rural and urban communities, offer flexibility by encouraging investment, and to enable the risks and costs of the investment borne by private investors through a fund structure.[76]

B. Statutory Analysis

i. Designation

As mentioned above, the Opportunity Zone provisions are codified under Section 1400Z of the Internal Revenue Code.[77] The statute defines a qualified Opportunity Zone as “a population census tract that is a low-income community that is designated as a qualified opportunity zone.”[78] For qualified Opportunity Zone designation, a low-income, population census tract essentially has to satisfy a three part test in which the State’s chief executive officer, by the end of the determination period (90-day period beginning on the TCJA’s enactment), shall: (1) nominate the tract of land to be designated as an Opportunity Zone; (2) send written notification to the United States’ Secretary of the Treasury about the Opportunity Zone nomination; and (3) the Treasury Secretary certifies the nomination and designates the tract of land as a qualified Opportunity Zone before the consideration period expires, which is usually thirty days.[79] The State’s chief executive officer may request that the Treasury Secretary grant a 30-day extension of either the determination or consideration period, or both.[80]

A few other provisions under Section 1400Z–1 regarding designations worth noting include a special rule for Puerto Rico, in which “[e]ach population census tract in Puerto Rico that is a low-income community shall be deemed to be certified and designated as a qualified opportunity zone.”[81] Low-income communities are defined as population census tracts where: (1) the tract’s poverty rate is at least 20 percent; (2) in areas outside a metropolitan area, the median family income of a tract “does not exceed 80 percent of statewide median family income[;]” or (3) where the tract is located within a metropolitan area, the tract’s median family income “does not exceed 80 percent of the greater of statewide median family income or the metropolitan area median family income.”[82] Aside from the Puerto Rico exception, the statute limits the number of tracts that can be designated qualified Opportunity Zones to no more than 25 percent of the State’s number of low-income communities.[83] However, if a State has less than 100 low-income communities, then 25 tracts can be designated as a qualified Opportunity Zone.[84] Additionally, the statute specifies that a tract will be designated a qualified Opportunity Zone for a period of ten years from the date the tract receives its Opportunity Zone designation.[85]

A few other provisions under Section 1400Z–1 regarding designations worth noting include a special rule for Puerto Rico, in which “[e]ach population census tract in Puerto Rico that is a low-income community shall be deemed to be certified and designated as a qualified opportunity zone.”[81] Low-income communities are defined as population census tracts where: (1) the tract’s poverty rate is at least 20 percent; (2) in areas outside a metropolitan area, the median family income of a tract “does not exceed 80 percent of statewide median family income[;]” or (3) where the tract is located within a metropolitan area, the tract’s median family income “does not exceed 80 percent of the greater of statewide median family income or the metropolitan area median family income.”[82] Aside from the Puerto Rico exception, the statute limits the number of tracts that can be designated qualified Opportunity Zones to no more than 25 percent of the State’s number of low-income communities.[83] However, if a State has less than 100 low-income communities, then 25 tracts can be designated as a qualified Opportunity Zone.[84] Additionally, the statute specifies that a tract will be designated a qualified Opportunity Zone for a period of ten years from the date the tract receives its Opportunity Zone designation.[85]

The Opportunity Zones provisions also extend to tracts of land that are contiguous with low-income communities.[86] In this scenario, the tract is not considered a low-income community and may still qualify for Opportunity Zone designation if: (1) the tract is contiguous with a low-income community that is a designated Opportunity Zone, and (2) the tract’s median family income does not exceed 125 percent of the contiguous low-income community’s median family income.[87] However, the statute limits the number of non-low-income tracts that can become a qualified Opportunity Zone.[88] This limitation mandates that no more than five percent of the State’s population census tracts can be designated as a qualified Opportunity Zone by being contiguous to a low-income community.[89]

The Opportunity Zones provisions also extend to tracts of land that are contiguous with low-income communities.[86] In this scenario, the tract is not considered a low-income community and may still qualify for Opportunity Zone designation if: (1) the tract is contiguous with a low-income community that is a designated Opportunity Zone, and (2) the tract’s median family income does not exceed 125 percent of the contiguous low-income community’s median family income.[87] However, the statute limits the number of non-low-income tracts that can become a qualified Opportunity Zone.[88] This limitation mandates that no more than five percent of the State’s population census tracts can be designated as a qualified Opportunity Zone by being contiguous to a low-income community.[89]

ii. Tax Effect

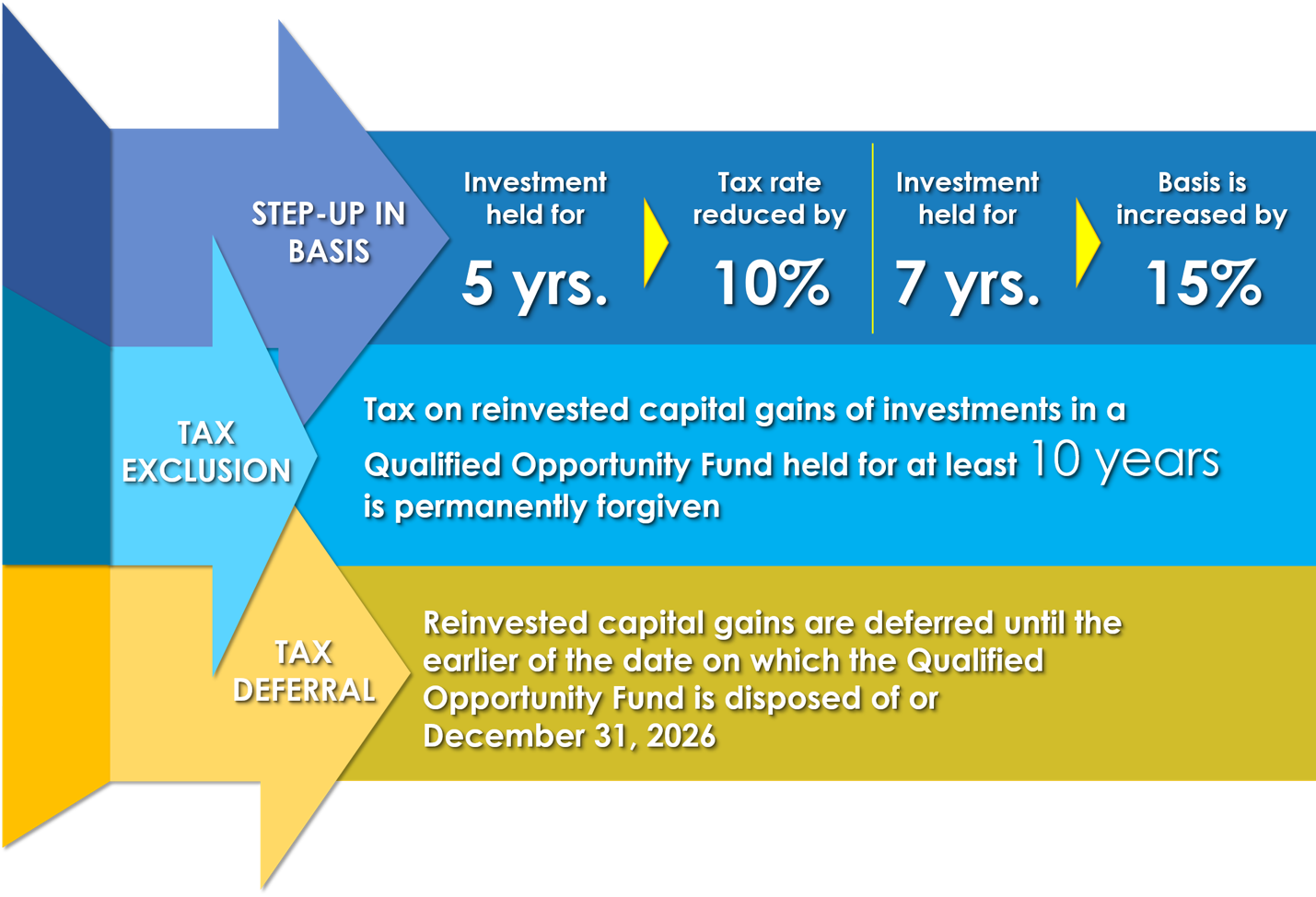

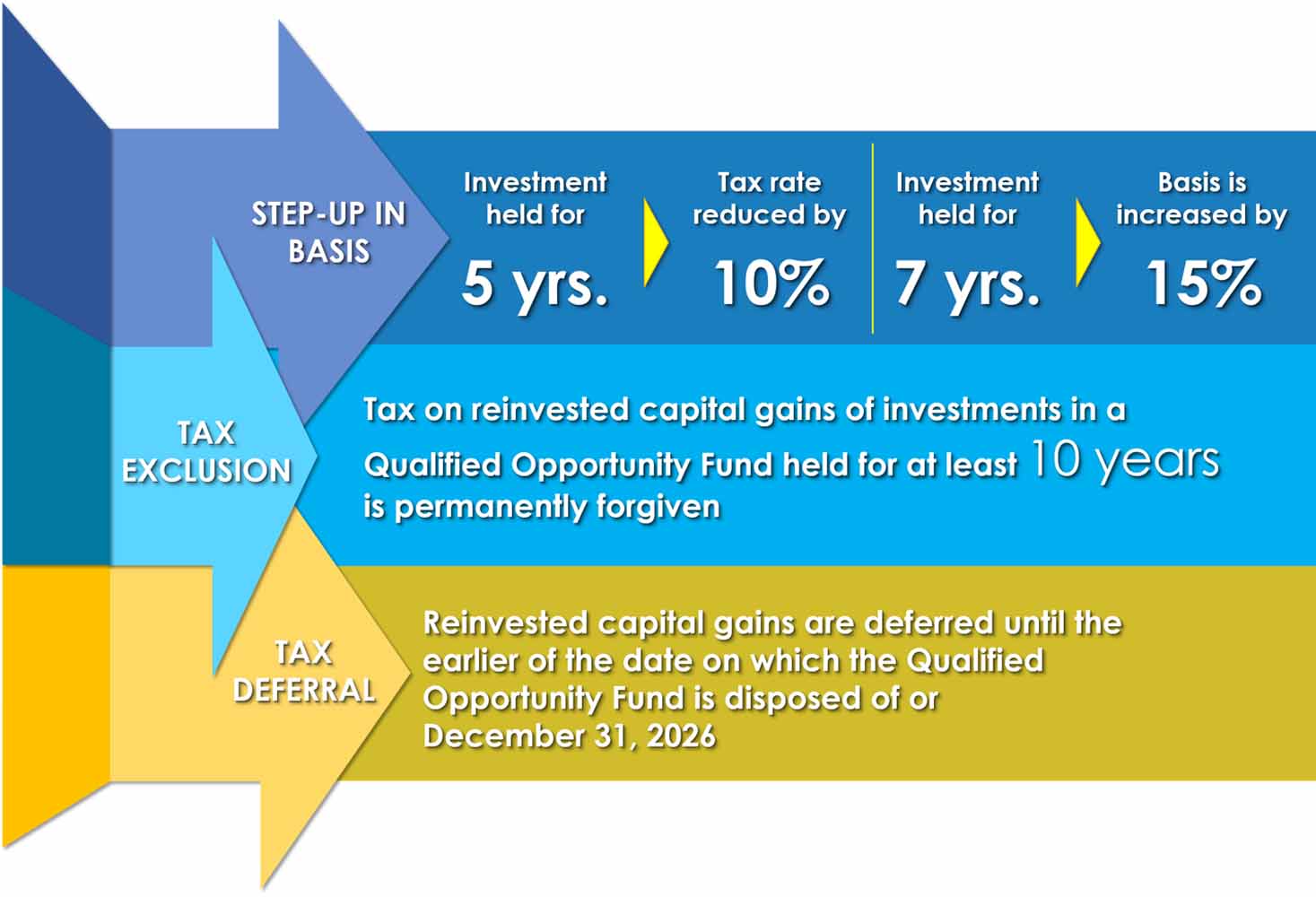

The Opportunity Zones provisions under the Internal Revenue Code provide investors with the ability to obtain favorable tax treatment. Considered a “once-in-a-lifetime tax benefit[,]” Opportunity Zones afford an investor the potential to partially exclude deferred capital gains that were used for Opportunity Zone investment and potentially fully exclude the entire appreciation of the investor’s Opportunity Zone investment depending on the holding period.[90] Section 1400Z-2 of the Internal Revenue Code introduces an Opportunity Zone’s tax treatment by describing an occurrence of a gain from either a sale or exchange of property held by a taxpayer with an unrelated person.[91] After the sale or exchange takes place, the taxpayer possesses an election that moves toward the investment into an Opportunity Zone.[92] This particular election entails that: (1) the taxpayer’s gross income for a taxable year does not include the amount of gain that does not exceed the basis of a taxpayer’s investment in a qualified opportunity fund during a 180-day period commencing on the date of the sale or exchange of the property described above; (2) the amount of gain excluded in the preceding point is included in gross income of a taxable year when the earlier of when the sale or exchange occurs, or December 31, 2026; and (3) if the property is held for at least ten years, a taxpayer’s basis in the investment receives a full step-up to the fair market value on the date of the sale or exchange date.[93] There are two scenarios where an election cannot be made, in which (a) an election is already made on the sale or exchange of the concerned property and (b) any sale or exchange made after December 31, 2026.[94]

Arguably, the most focused on and popular sections under Section 1400Z–2 are the deferred gains provisions, which lay out the tax benefits of investing in Opportunity Zones.[95] Gains from the sale or exchange of property that are invested into Opportunity Zones are deferred until the earlier of the sale or exchange of the interest in the Opportunity Zone or December 31, 2026.[96] Once the deferred gain is recognized, the amount of gain that is included in gross income is the excess of the lesser of the deferred gain or the fair market value of the investment, over the taxpayer’s basis in his or her Opportunity Zone investment.[97]

A taxpayer’s basis can change based on different circumstances. Before a sale or exchange of qualified Opportunity Zone property occurs and the favorable tax treatment takes effect, the basis in an Opportunity Zone investment is zero.[98] That basis increases to the amount of gain that was previously deferred, but now recognized, from the investment in the Opportunity Zone.[99] However, the taxpayer has an incentive to hold the Opportunity Zone investment for a longer period of time. If the taxpayer holds his or her investment for at least five years, the basis of the investment is increased by 10 percent of the deferred gain.[100] If a taxpayer holds the opportunity investment for at least seven years, the basis of the investment experiences a five percent increase, resulting in a 15 percent total basis increase of the deferred gain.[101] Finally, if a taxpayer holds his or her Opportunity Zone investment for at least ten years, the basis of the investment into the Opportunity Zone shall equal the fair market value of the qualified Opportunity Zone investment on the date the investment is sold or exchanged.[102] According to the Treasury Regulations, a taxpayer must sell their Opportunity Zone investment by December 31, 2047 in order to take advantage of the step-up in basis to fair market value tax benefit after the ten-year holding period anniversary.[103]

The Opportunity Zone statutes lay out some definitions to keep in mind with the information described above. First, qualified Opportunity Zone property under the statute means property that is: “(i) qualified opportunity zone stock, (ii) qualified opportunity zone partnership interest, or (iii) qualified opportunity zone business property.”[104] A domestic corporation’s stock can be considered qualified Opportunity Zone stock as long as the stock is acquired after December 31, 2017, “at its original issue . . . from the corporation solely in exchange for cash,” the corporation was a qualified Opportunity Zone business or, if a new corporation, is in the process of becoming one at the time the stock was issued, and the corporation qualified as a qualified Opportunity Zone business “during substantially all of the qualified opportunity fund’s holding period.”[105] A capital or profit interest in a domestic partnership is considered a qualified Opportunity Zone partnership interest if it meets the same requirements as qualified Opportunity Zone stock except for substituting stock for partnership interest.[106]

A qualified opportunity zone business property’s definition is similar in some respects to both qualified Opportunity Zone stock and partnership interest with the property being acquired through purchase by a qualified opportunity fund after December 31, 2017, but there are unique provisions considering substantial improvement. The property’s original use begins within the qualified opportunity fund or the fund substantially improves the property.[107] With respect to qualified Opportunity Zone partnership interests, substantial improvement is defined in the statute as over the course of a 30-month period that commences after the property is acquired, “additions to basis with respect to such property in the hands of the qualified opportunity fund exceed an amount equal to the adjusted basis of such property at the beginning of such 30-month period in the hands of the qualified opportunity fund.”[108] Additionally, the property needs to be in a qualified Opportunity Zone for a substantial amount of time during the qualified opportunity fund’s holding period.[109]

A qualified Opportunity Zone business is a trade or business where a substantial amount of the tangible property owned or leased by a taxpayer is qualified Opportunity Zone business property, is a qualified business entity, and is not property described in Section 144(c)(6)(B) of the Internal Revenue Code, such as gambling facilities, country clubs, and golf courses among others.[110] If the tangible property ceases its status as a qualified Opportunity Zone business property, the property can continue this status for the lesser of (1) five years after when the property no longer qualifies or (2) the date when the tangible property “is no longer held by the qualified Opportunity Zone business.”[111] In the event a qualified opportunity fund does not meet its requirement to hold 90 percent of its assets in a qualified opportunity property, the fund shall pay a penalty for each month it fails to qualify.[112]

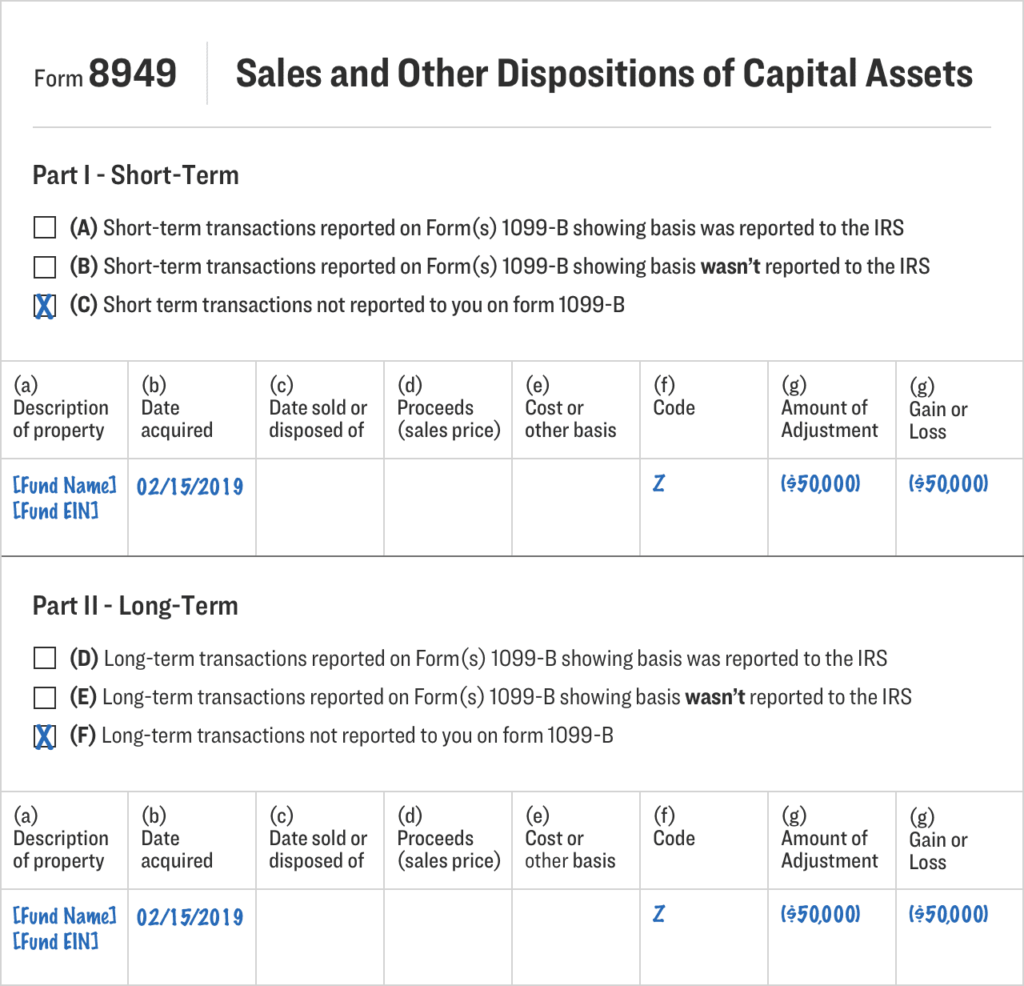

C. Other Significant Opportunity Zone Items

Qualified opportunity funds are established through a self-certification process by filing IRS Form 8996 with the qualified opportunity fund’s initial federal income tax return.[113] Form 8996 must be filed each year by the qualified opportunity fund’s tax due date as part of its annual self-certification requirement.[114] As for individual investors, they need to file two Forms 8949 (Sales and Other Dispositions of Capital Assets) to trigger their temporary deferral of their capital gain that was invested into a qualified opportunity fund.[115] One submission is to report the capital gain activity and the other to report the deferral of the capital gain.[116] To file a Form 8949 correctly for the capital gain deferral, the eligible taxpayer (investor) should follow the steps below:[117]

- Report the full amount of the capital gain as if no qualifying opportunity fund election was made.

- Report the eligible deferred gain by entering it on its own row in Part I (Short-Term Transactions), and check the applicable box (for example, Box C: “Short-term transactions not reported to you on Form 1099-B”) or if a long-term transaction, report the eligible deferred gain in Part II and check the applicable box, such as Box F: “Long-term transactions not reported to you on Form 1099-B[.]” For the applicable Part and row of where the transaction will be entered, write “QO Fund” and the name and taxpayer ID of the qualified opportunity fund in column (a), the date acquired in column (b), and code Z in column (f).

- Write the amount of the deferred gain as a negative number in column (g) and fill in column (h) with the column (g) amount.

In addition to filing Form 8949, the eligible taxpayer (investor) must file a Form 8997 (Initial and Annual Statement of Qualified Opportunity Fund (QOF) Investments) if the taxpayer holds a qualified opportunity fund interest at any time during the tax year.[118] Form 8997 is due the same time as the taxpayer’s federal income tax return deadline, including extensions.[119] Below are images from Charlie Anastasi of CADRE illustrating an example of a completed Form 8949 to elect the temporary deferral of capital gains that will be invested into a qualified opportunity fund.[120]

Revisiting the annual self-certification requirement, a qualified opportunity fund must also satisfy three tests on an ongoing basis: (1) an organization test; (2) a purpose test; and (3) an asset test.[121] For the organization test, the qualified opportunity fund must be organized as either a corporation or partnership, including limited liability companies (LLCs) that elect to be treated as a partnership for tax purposes.[122] A pre-existing entity can become a qualified opportunity fund provided they self-certify and establish an initial qualified opportunity fund date if the entity otherwise qualifies.[123] As for the purpose test, the entity “must be an ‘investment vehicle’ formed for the purpose of investing in [qualified Opportunity Zone property.]”[124] Also, Form 8996 mandates that the entity certifies through a statement in its organizing documents that its purpose is to invest in qualified Opportunity Zone property and “a description of [the qualified Opportunity Zone] business or businesses[.]”[125] Below is a draft of a provision we prepared for a client in order to satisfy the purpose test of an LLC, which is treated as a partnership for tax purposes, that was created for a qualified opportunity fund:

A. Purpose of LLC. The purpose of the company shall be to qualify as a qualified opportunity fund under the TCJA and to directly or indirectly, through the company and/or one or more of its subsidiaries, identify source, originate, acquire, maintain, own, manage, finance, refinance, hold, sell, reposition, pledge, hypothecate, hedge, exchange, invest, and otherwise, deal in and with diversified portfolios of commercial real estate properties or joint-ventured equity investments, and other real estate related assets, that are compelling from a risk return perspective particular with a focus on multi-family rental units and other commercial real estate development or redevelopment projects located in a qualified opportunity zone as designated by the TCJA that is considered qualified opportunity zone property, including any asset that is deemed to be a qualified opportunity zone property that is not real property in accordance with the terms of this agreement. Such activity of the qualified opportunity fund shall be engaged either directly or through a qualified opportunity zone business.

Finally, the qualified opportunity fund needs to meet an asset test, in which “the corporation’s or partnership’s assets must be comprised of at least 90 [percent of qualified Opportunity Zone] [p]roperty.”[126] In order to comply with the asset test, the value of the corporation or partnership’s qualified opportunity fund assets must average 90 percent considering the last day of the first 6-month measurement period and the second 6-month measurement period.[127] For example, let us assume a partnership’s average total assets is $100 million for the year. If a partnership’s asset value in a qualified opportunity fund is $92 million on the last day for the first 6-month period and $88 million on the last day for the second sixth-month period, the average value of assets in a qualified Opportunity Zone is $90 million. Next, the $90 million in qualified opportunity fund assets are divided by the $100 million average total asset value for the year. This computation would result in the necessary 90 percent average figure as required by the asset test. This calculation needs to be computed annually on Form 8996.[128] Failure to achieve the 90 percent asset test will result in a penalty imposed against the qualified opportunity fund.[129]

D. Example Tax Calculations

This section will illustrate a series of scenarios based on four different tax consequences that pertain to the investment and sale of an Opportunity Zone investment by a taxpayer in order to better understand the Opportunity Zone provisions. The scenarios will cover: (1) the investment into a qualified opportunity fund; (2) sale of qualified Opportunity Zone investment with at least a five-year holding period; (3) sale of qualified Opportunity Zone investment with at least a seven-year holding period; and (4) sale of Opportunity Zone investment with at least a ten-year holding period.

i. The Investment of Capital Gains into a Qualified Opportunity Fund

Scenario 1: Jane Smith sold to an unrelated party 2,000 shares of her Walt Disney Company (Disney) stock for $250,000 in 2018. Her basis in the stock was $150,000 and she held the shares for six years. Jane is currently facing a capital gains tax on her $100,000 gain from the sale of her Disney stock. However, Jane opts to invest her $100,000 gain into a qualified opportunity fund within 180 days of the stock’s sale date. The fund is established for the purpose of investing in two designated assets: a proprietary interest in a sports facility and real estate that can develop into a stadium district.

Scenario 1 Tax Treatment: Jane started the election described under Section 1400Z–2(a)(1), in which Jane sold her Disney shares to an unrelated party for a gain. She invested the gain into a qualified opportunity fund within 180 days of the sale as required by Section 1400Z–2(a)(1)(A). According to Section 1400Z–2(b)(1)(A) –(B), Jane’s gain from the stock sale is deferred until the earlier of the date of her investment in the qualified Opportunity Zone is sold or December 31, 2026.

ii. Qualified Opportunity Zone Property Sold After 5 Years, but Less Than 7 Years

Scenario 2: Considering the facts from Scenario 1, Jane held on to her qualified Opportunity Zone investment interest for five years (2023). Within a few days after the five-year holding period anniversary, Jane sold her investment interest for $150,000.

Scenario 2 Tax Treatment: First, the deferred $100,000 capital gain mentioned above will be recognized and included in gross income in 2023 as stated under Section 1400Z–2(b)(1)(A) since it is the earlier of the sale date or December 31, 2026. Next, Section 1400Z–2(b)(2)(A) calls for a gain to be calculated but Jane’s basis needs to be determined first. Since Jane held her investment interest for five years, she is entitled to a basis increase of 10% of the deferred gain pursuant to Section 1400Z–2(b)(2)(B)(iii). Her initial basis in the Opportunity Zone investment is zero pursuant to Section 1400Z–2(b)(2)(B)(i), and will be increased by $10,000 ($100,000 x 10%). As a result, Jane’s basis in her Opportunity Zone investment is $10,000. Since Jane’s basis has been determined, the previously deferred gain is reduced to $90,000 and will represent the amount included in gross income for 2023. This was determined by using the $100,000 deferred gain since it is the lesser figure compared to the fair market value of the investment ($150,000) as described in Section 1400Z–2(b)(2)(A)(i), and then subtracting Jane’s $10,000 basis from the $100,000 deferred gain as afforded by Section 1400Z–2(b)(2)(A)(i)–(ii). The $90,000 taxable amount could have also been determined by taking the $100,000 deferred gain and multiplying by 90% (100% minus 10% step-up (exclusion)). As a result, Jane will only pay capital gains tax against $90,000 basis of the previously deferred gain.

As for Jane’s tax liability related to the sale of her qualified Opportunity Zone investment, she will only pay capital gains tax on $50,000. This amount is configured by subtracting Jane’s basis in her qualified Opportunity Zone investment from the $150,000 selling price. Her basis in the investment is calculated by adding the $90,000 deferred gain to her $10,000 basis pursuant to Section 1400Z–2(b)(2)(B)(ii). By subtracting the investment’s basis of $100,000 from the $150,000 selling price, Jane will only pay capital gains tax on $50,000.

iii. Qualified Opportunity Zone Property Sold After 7 Years, but Less Than 10 Years

Scenario 3: Considering the facts from Scenario 1, Jane held onto her qualified Opportunity Zone investment for seven years (2025). Within a couple of days after the seven-year holding period anniversary, Jane sold her investment for $175,000.

Scenario 3 Tax Treatment: Similar to Scenario 2’s tax treatment, the $100,000 deferred capital gain will be recognized in 2025 since the sale of the qualified Opportunity Zone investment occurred before the end of 2026. Jane’s basis will need to be determined on this sale as well. As stated in Scenario 2, Jane’s initial basis is zero. However, unlike the basis increase of 10 percent of the deferred gain in Scenario 2, in this scenario Jane will be able to increase her basis another 5 percent, thereby resulting in a 15 percent total basis increase as allowed in Section 1400Z–2(b)(2)(B)(iv). Thus, Jane’s basis for the purpose of determining the deferred gain is $15,000 ($100,000 x 15%). Using Section 1400Z–2(b)(2)(A)(i), the $100,000 deferred gain is less than the $175,000 sales price of the qualified Opportunity Zone investment. Therefore, the basis of $15,000 will be subtracted from the $100,000 investment. As a result, Jane will pay capital gains taxes on the new $85,000 reduced deferred gain figure. Alternatively, the short cut could be used to get the new $85,000 deferred gain amount by multiplying the $100,000 investment by 85% (100% less 15% step-up).

Considering the tax liability for the sale of her qualified Opportunity Zone investment, Jane will pay capital gains tax on $75,000. Similar to Scenario 2, Jane’s basis in her Opportunity Zone investment will increase from $15,000 to $100,000 when she adds the new deferred gain of $85,000 to her basis. She will then subtract her new basis of $100,000 from the $175,000 selling price of her Opportunity Zone investment to obtain her $75,000 gain that is subject to capital gains tax.

iv. Qualified Opportunity Zone Property Sold After 10 Years

Scenario 4: Considering the facts from Scenario 1, Jane held on to her qualified Opportunity Zone investment for ten years and sold her investment for $200,000.

Scenario 4 Tax Treatment: For purposes of the $100,000 deferred gain that was invested into a qualified opportunity fund, Jane would experience the same tax treatment under Scenario 3. She will have a $15,000 basis in her qualified Opportunity Zone investment, which is then subtracted from the $100,000 deferred gain that was used towards the investment to compute a new deferred gain of $85,000. She will have to recognize this gain on her 2026 tax returns since December 31, 2026 occurred before the sale date (2028).

If Jane holds on to her qualified Opportunity Zone investment for at least ten years, she is entitled to the most substantial tax incentive the Opportunity Zone provisions offer. Under Section 1400Z–2(c), if a taxpayer holds their qualified Opportunity Zone investment for at least ten years, the taxpayer’s basis in the investment increases to the fair market value of the investment on the sale date. Considering the tax treatment in this scenario, Jane had a basis of $15,000 for her qualified Opportunity Zone investment. With the new deferred gain of $85,000, that deferred gain is added to the basis to make Jane’s new investment basis $100,000. Using the full step-up in basis incentive for a sale occurring after ten years of investment, Jane’s basis increases to the sale price of $200,000. As a result, Jane’s sale of her qualified Opportunity Zone investment is tax free ($200,000 sale price less $200,000 basis).

IV. Opportunity Zone Impact on Local Communities and Sports Industry

A. Local Community Impact

With the birth of Opportunity Zones, communities can develop and thereby “catalyze prosperity and access for underserved Americans.”[130] Opportunity Zones have the ability to generate uncapped billions or trillions of dollars of investments into historically impoverished urban and rural areas across the entire country and its territories.[131] “For communities with increasing housing insecurity and growing economic inequality, an Opportunity Zone designation provides a chance to shape strategies and policies that harness this powerful incentive, while serving the needs of current and future residents.”[132] As such, communities need to prepare themselves for Opportunity Zone investments and leverage those investments in order to transform.[133]

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) published a toolkit in September of 2019 that shows the steps that communities need to undertake in order to transform, become inclusive, and promote economic development within its Opportunity Zone tracts.[134] The first step involves understanding the needs and opportunities in Opportunity Zones, in which communities should engage with residents, businesses, and key stakeholders to understand their needs, and evaluate and plan for the impact that investments may have on their communities.[135] The next step concerns aligning and leveraging “place-based assets and resources to facilitate and steer market investment toward community economic development[]” in order to realize the full benefits of Opportunity Zone investments.[136] The third step consists of establishing “policy tools and incentives to promote equitable and inclusive growth[,]” such as future project pipelines and tax credits.[137] The final step encourages communities to “[p]artner with aligned organizations to support equitable and inclusive opportunities[]” in order to ensure lasting partnerships and leverage Opportunity Zone investments over time.[138]

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) published a toolkit in September of 2019 that shows the steps that communities need to undertake in order to transform, become inclusive, and promote economic development within its Opportunity Zone tracts.[134] The first step involves understanding the needs and opportunities in Opportunity Zones, in which communities should engage with residents, businesses, and key stakeholders to understand their needs, and evaluate and plan for the impact that investments may have on their communities.[135] The next step concerns aligning and leveraging “place-based assets and resources to facilitate and steer market investment toward community economic development[]” in order to realize the full benefits of Opportunity Zone investments.[136] The third step consists of establishing “policy tools and incentives to promote equitable and inclusive growth[,]” such as future project pipelines and tax credits.[137] The final step encourages communities to “[p]artner with aligned organizations to support equitable and inclusive opportunities[]” in order to ensure lasting partnerships and leverage Opportunity Zone investments over time.[138]

Currently, Opportunity Zones have experienced early success and investments continue

to occur.[139] Opportunity Zone investments initially took some time to gain traction since there was a shortage of Treasury Department guidance in the beginning pertaining to the Opportunity Zone certification process.[140] However, this slow start quickly recovered as billions of dollars were poured into low-income communities.[141] The U.S. Government aimed for investments of $10 to $13 billion during the first two years of the program.[142] The most conservative estimate from March 2020 states that $10 billion has been invested in Opportunity Zones.[143] However, Novogradac estimates that the actual Opportunity Zone investments range from $20 to $30 billion due to the rolling nature of surveys and limited public information.[144] But we will soon discover that even the $20 to $30 billion estimate was grossly understated. Investors are hopeful that some future changes will take place, such as reporting requirements and data that allow for comparison and measurement of an investment’s effectiveness.[145] Also, some would like to see an extension of the December 31, 2026 deadline to encourage more investments and take advantage of the seven-year capital gain deferral since the deadline for a seven-year deferral expired on December 31, 2019.[146]

Despite the remarkable progress of Opportunity Zones, the Covid-19 pandemic has caused some investments to take a “wait-and-see approach.”[147] According to a study conducted by the Economic Innovation Group, 52 percent of survey respondents said Covid-19 had a negative impact on their Opportunity Zone investments.[148] However, the survey noted an encouraging, key point in which investors are remaining engaged in their Opportunity Zone investments and are looking to contribute more capital.[149] The majority of survey respondents are optimistic about the future of Opportunity Zone investments, and 49 percent of Opportunity Zone fund managers are confident that their Opportunity Zone strategies are “well-suited [for] the current environment.”[150] Despite the positive future outlook of Opportunity Zones during the Covid-19 pandemic, survey respondents are hoping for an extension of the investment deadline beyond 2026 to maintain short-term enthusiasm.[151]

Despite the remarkable progress of Opportunity Zones, the Covid-19 pandemic has caused some investments to take a “wait-and-see approach.”[147] According to a study conducted by the Economic Innovation Group, 52 percent of survey respondents said Covid-19 had a negative impact on their Opportunity Zone investments.[148] However, the survey noted an encouraging, key point in which investors are remaining engaged in their Opportunity Zone investments and are looking to contribute more capital.[149] The majority of survey respondents are optimistic about the future of Opportunity Zone investments, and 49 percent of Opportunity Zone fund managers are confident that their Opportunity Zone strategies are “well-suited [for] the current environment.”[150] Despite the positive future outlook of Opportunity Zones during the Covid-19 pandemic, survey respondents are hoping for an extension of the investment deadline beyond 2026 to maintain short-term enthusiasm.[151]

Going forward, the Opportunity Zones provisions are considered “key to the nation’s recovery.”[152] Opportunity Zones provide investors an alternative investment option to the stock market.[153] They are seen as crucial for economic stimulus, job creation, and the revitalization of the country’s distressed communities.[154] The distressed communities have been considered disproportionately impacted by the Covid-19 pandemic and the Opportunity Zones provisions will help ensure their recovery.[155] Some believe that investments in Opportunity Zones during the Covid-19 recovery will result in recovery of other key economic areas, such as real estate, retail, infrastructure, improved health care, and decreased crime.[156] As a result, the positive impacts of Opportunity Zones will improve people’s quality of life as the nation recovers.[157]

B. Sports Industry Impact

The sports industry is considered to be among the best positioned to utilize Opportunity Zones.[158] The industry got its first glimpse of how successful Opportunity Zones could be with the opening of Nationals Park in 2008.[159] The objective was to revive the Anacostia neighborhood of Washington, D.C., and the ballpark was part of the revitalization that led to residential and commercial development.[160] The success of Nationals Park resulted in the above-mentioned Investing in Opportunity Act in order to establish Opportunity Zones but the Bill did not become law.[161] However, the passage of the TCJA set the stage for Opportunity Zones to take flight.[162]

According to the Sports Business Journal, there are four pathways where the sports industry and Opportunity Zones intersect:[163]

According to the Sports Business Journal, there are four pathways where the sports industry and Opportunity Zones intersect:[163]

- Sports Venue Construction and Renovation: At least half of the sports venues located in the United States for Major League Baseball, the National Football League, and the National Basketball Association are either in an Opportunity Zone or adjacent to an Opportunity Zone. Teams that are looking to either renovate or construct new venues could raise the necessary capital through the Opportunity Zone program. This would result in more private financing rather than public financing, which is criticized by elected officials and taxpayers.

- Ancillary Mixed-Use Districts: In order to generate broader economic and community benefits on both game days and non-game days, a team or stadium owner builds a district around several key features and destinations, such as retail, office, housing, and hospitality.

- Youth Sports Complexes: In the past decade, there has been a boom of constructing youth sports facilities. However, there is a shortage of youth sports facilities in low-income areas. Opportunity Zone investments for youth sports facilities satisfies the policy objective of the Opportunity Zone program and could halt the decline of youth sports participation in low-income communities.

- Sports-related Operating Businesses: Although real estate is the popular Opportunity Zone investment, one of the major goals of Opportunity Zones was to invest in businesses to help create jobs for low-income communities. A successful positioning of ventures in Opportunity Zones could have a positive effect on the prospects of esports, sports media, and incubators as well.

The sports industry can play a major role in advancing the economic and societal benefits of the Opportunity Zones program.[164] It is estimated that there is $6 trillion in unrealized capital gains in the United States, and that amount of money has the power and ability to transform low-income communities and create jobs.[165] For some professional sports teams, their current stadium already sits in an Opportunity Zone.[166] As such, investments can be made into a team’s current facility for possible renovations or towards the construction of a new facility.[167] Also, if the investment is held for at least ten years, any appreciation in the Opportunity Zone investment that is sold and would normally be subject to capital gains tax is tax free due to the basis step-up to fair market value, and the investors can receive returns on investments as much as 70 percent.[168] Additionally, some investors will receive a windfall from the Opportunity Zone program because an investment was already made before the tax incentives became law.[169]

In addition to either constructing a new sports facility or renovating a current facility, if the tract of land the stadium sits on is a qualified Opportunity Zone, investments can be poured into the zone to develop a stadium entertainment district.[170] This would include establishing bars, restaurants, and hotels among other attractions.[171] This would support the notion that sports facilities drive economic growth and development, and can positively impact a local community.[172] The only restriction is that the investments cannot develop “sin businesses” such as casinos or marijuana distributors.[173] Otherwise, owners can build on their current stadiums with new amenities or construct new businesses for their stadium entertainment district without much restriction on products and services.[174]

A potential intersection of the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) and the Opportunity Zones provisions may have an impact on the relationship between banks and the sports industry.[175] “Regulators from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency appointed by [former] President Donald Trump have drafted a list of new ways banks could meet their obligations to qualify for tax breaks under proposed changes to the CRA.”[176] The CRA’s proposed changes include a line concerning sports stadiums and Opportunity Zones entitled “‘Investment in a qualified opportunity fund, established to finance improvements to an athletic stadium in an [O]pportunity [Z]one that is also (a low- or moderate-income) census tract.’”[177] If these proposed changes are finalized, banks and other financial institutions could favor investments into sports facility Opportunity Zones over others.[178] This way, banks will be able to meet their CRA obligations by financing a low risk, profitable investment like sports facilities.[179]

A potential intersection of the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) and the Opportunity Zones provisions may have an impact on the relationship between banks and the sports industry.[175] “Regulators from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency appointed by [former] President Donald Trump have drafted a list of new ways banks could meet their obligations to qualify for tax breaks under proposed changes to the CRA.”[176] The CRA’s proposed changes include a line concerning sports stadiums and Opportunity Zones entitled “‘Investment in a qualified opportunity fund, established to finance improvements to an athletic stadium in an [O]pportunity [Z]one that is also (a low- or moderate-income) census tract.’”[177] If these proposed changes are finalized, banks and other financial institutions could favor investments into sports facility Opportunity Zones over others.[178] This way, banks will be able to meet their CRA obligations by financing a low risk, profitable investment like sports facilities.[179]

C. Sports Industry Opportunity Zone Sites

As previously stated, there are several sports facilities that are situated in an Opportunity Zone. This would also include stadium entertainment districts in which the stadium is the main focus or attraction. Through investments in these stadium-occupied Opportunity Zones, new construction for stadiums and their entertainment districts will occur.[180] One point to reiterate about current sports facilities and districts and Opportunity Zones is the concept of substantial improvement of property.[181] Preexisting stadiums would not be considered original use assets since they have already been initially constructed, but they qualify for Opportunity Zone treatment under substantial improvement.[182] If the stadium and/or its district is considered qualified Opportunity Zone business property owned or leased by an eligible entity, it must meet the substantial improvement requirement.[183]

The . . . property is treated as substantially improved by an eligible entity only if it meets the requirements of section 1400Z-2(d)(2)(D)(ii) during the 30-month substantial improvement period. The property has been substantially improved when the additions to basis of the property in the hands of the [qualified opportunity fund] exceed an amount equal to the adjusted basis of such property at the beginning of such 30-month period in the hands of the [qualified opportunity fund].[184]

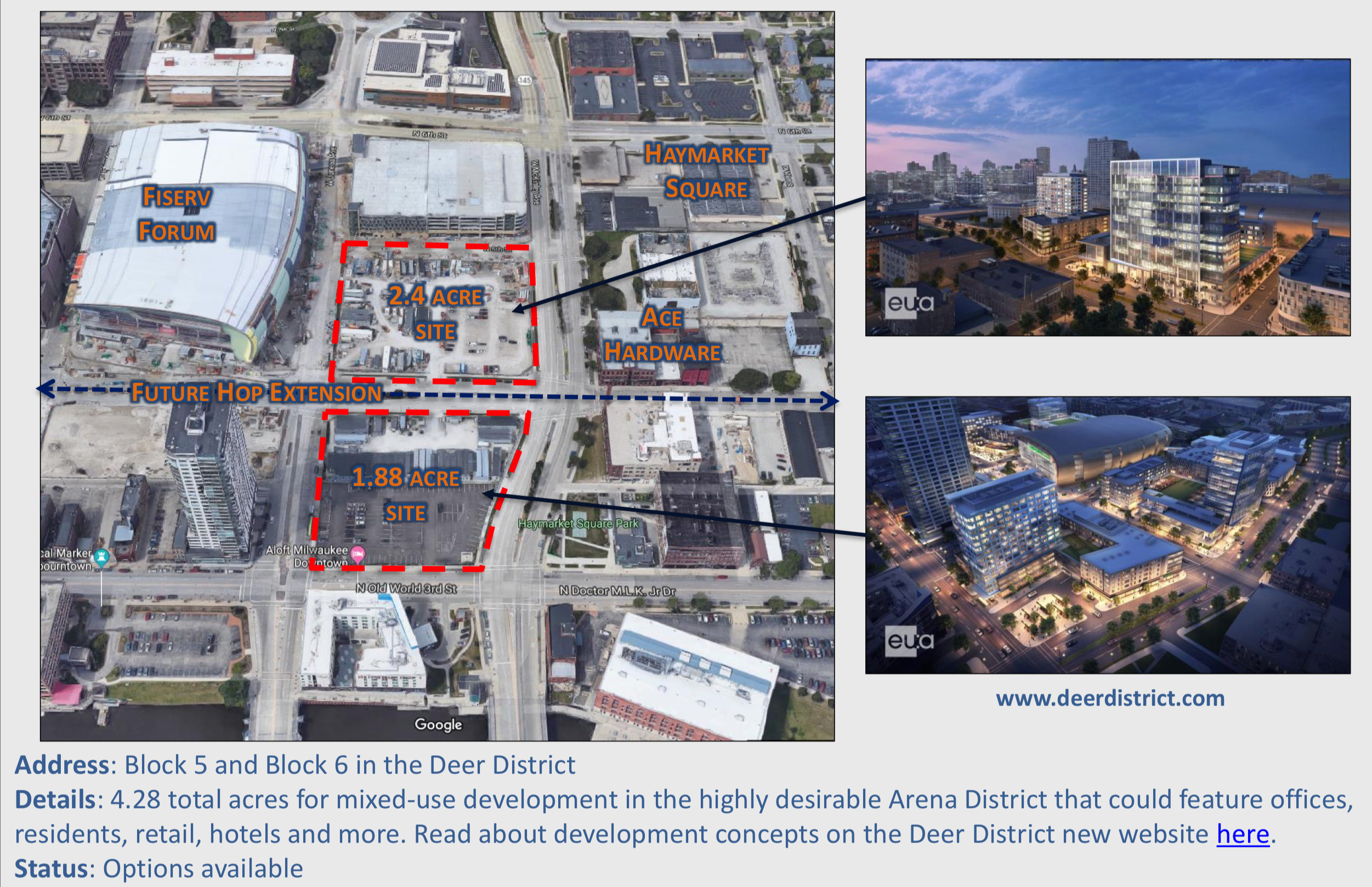

As discussed above, ownership in a sports facility is one of the two main investable designated assets for a sports industry opportunity fund. The following tables illustrate which actively used sports facilities are situated in an Opportunity Zone across the four major North American professional sports leagues:[185]

National Football League (NFL)

| Sports Facility | Sports Franchise | Location |

| Lumen Field | Seattle Seahawks | Seattle, Washington |

| Empower Field at Mile High | Denver Broncos | Denver, Colorado |

| FedExField | The Washington Football Club | Landover, Maryland |

| FirstEnergy Stadium | Cleveland Browns | Cleveland, Ohio |

| Ford Field | Detroit Lions | Detroit, Michigan |

| SoFi Stadium | Los Angeles Rams and Chargers | Inglewood, California |

| Lucas Oil Stadium | Indianapolis Colts | Indianapolis, Indiana |

| M&T Bank Stadium | Baltimore Ravens | Baltimore, Maryland |

| Mercedes-Benz Stadium | Atlanta Falcons | Atlanta, Georgia |

| Mercedes-Benz Superdome | New Orleans Saints | New Orleans, Louisiana |

| Nissan Stadium | Tennessee Titans | Nashville, Tennessee |

| NRG Stadium | Houston Texans | Houston, Texas |

| Paul Brown Stadium | Cincinnati Bengals | Cincinnati, Ohio |

| Allegiant Stadium | Las Vegas Raiders | Las Vegas, Nevada |

| Raymond James Stadium | Tampa Bay Buccaneers | Tampa, Florida |

| TIAA Bank Field | Jacksonville Jaguars | Jacksonville, Florida |

Major League Baseball (MLB)

| Sports Facility | Sports Franchise | Location |

| Busch Stadium | St. Louis Cardinals | St. Louis, Missouri |

| Chase Field | Arizona Diamondback | Phoenix, Arizona |

| Comerica Park | Detroit Tigers | Detroit, Michigan |

| Great American Ball Park | Cincinnati Reds | Cincinnati, Ohio |

| American Family Field | Milwaukee Brewers | Milwaukee, Wisconsin |

| Minute Maid Park | Houston Astros | Houston, Texas |

| Petco Park | San Diego Padres | San Diego, California |

| Progressive Field | Cleveland Indians | Cleveland, Ohio |

| RingCentral Coliseum | Oakland Athletics | Oakland, California |

| T-Mobile Park | Seattle Mariners | Seattle, Washington |

| Tropicana Field | Tampa Bay Rays | Tampa, Florida |

| Yankee Stadium | New York Yankees | New York, New York |

National Hockey League (NHL)

| Sports Facility | Sports Franchise | Location |

| Amalie Arena | Tampa Bay Lightning | Tampa, Florida |

| KeyBank Center | Buffalos Sabres | Buffalo, New York |

| Little Caesars Arena | Detroit Red Wings | Detroit, Michigan |

| Prudential Center | New Jersey Devils | Newark, New Jersey |

| Xcel Energy Center | Minnesota Wild | St. Paul, Minnesota |

National Basketball Association (NBA)

| Sports Facility | Sports Franchise | Location |

| AT&T Center | San Antonio Spurs | San Antonio, Texas |

| Bankers Life Fieldhouse | Indiana Pacers | Indianapolis, Indiana |

| Chesapeake Energy Arena | Oklahoma City Thunder | Oklahoma City, Oklahoma |

| FedExForum | Memphis Grizzlies | Memphis, Tennessee |

| Golden 1 Center | Sacramento Kings | Sacramento, California |

| Little Caesars Arena | Detroit Pistons | Detroit, Michigan |

| Moda Center | Portland Trailblazers | Portland, Oregon |

| Rocket Mortgage Fieldhouse | Cleveland Cavaliers | Cleveland, Ohio |

| Smoothie King Center | New Orleans Pelicans | New Orleans, Louisiana |

| Phoenix Suns Arena | Phoenix Suns | Phoenix, Arizona |

| Toyota Center | Houston Rockets | Houston, Texas |

| Vivint Arena | Utah Jazz | Salt Lake City, Utah |

Amongst the NFL stadiums, Jimmy Atkinson in a 2019 article dove into potential Opportunity Zone investments.[186] The focus of his analysis was the stadium and the area surrounding the stadiums, the entertainment districts (or as we affectionately call them sports.comms), which are the second main investable asset in a sports opportunity fund.[187] Below are the highlights from Atkinson’s article about potential Opportunity Zone investments in the eligible NFL stadiums:[188]

i. Within an Opportunity Zone

-

-

-

- Atlanta Falcons (Mercedes-Benz Stadium): Commercial and residential real estate prospects surround the stadium that would be eligible for Opportunity Zone investment.

- Baltimore Ravens (M&T Bank Stadium): Recent $120 million renovation project for the stadium includes a new escalator and elevator system along with upgrades for the stadium’s sound system and club-level concession stands.

- Cincinnati Bengals (Paul Brown Stadium): Built in 2000, the stadium is starting to show its age and is in need of upgrades.

- Cleveland Browns (FirstEnergy Stadium): Like Cincinnati, the Browns’ stadium is in need of a renovation, and there have been rumors of a major stadium modernization project or new stadium construction.

- Denver Broncos (Empower Field at Mile High): The parking lots present a potential Opportunity Zone investment to develop a sports.comm around the stadium.

- Detroit Lions (Ford Field): The stadium recently underwent a $100 million renovation, but there are opportunities around the stadium that are prime for investment.

- Houston Texans (NRG Stadium): Although not undergoing any renovation plans, NRG Park, where NRG stadium is located, could experience some renovation funding for upgrades and maintenance with the Astrodome (also located in NRG Park) generating revenue once again.

- Indianapolis Colts (Lucas Oil Stadium): No current plans, but the stadium sits in an Opportunity Zone.

- Jacksonville Jaguars (TIAA Bank Field): Built in 1995, the stadium has undergone several capital improvements with the most recent being in 2015 to renovate the stadium’s club level seating among other projects.

- Las Vegas Raiders (Allegiant Stadium): Just opened in 2020, this stadium’s $1.8 billion funding could very well have been partially funded through a qualified opportunity fund since the stadium sits in an Opportunity Zone.

- New Orleans Saints (Mercedes-Benz Superdome): No current projects as of now, but with New Orleans hosting the 2024 Super Bowl, there could be the potential for Opportunity Zone investment in anticipation of the Super Bowl.

- Seattle Seahawks (Lumen Field): Opened in 2002, the stadium has not undergone an extensive stadium renovation project.

- Tampa Bay Buccaneers (Raymond James Stadium): Recently experienced $160 million in upgrades as the stadium hosted the 2021 Super Bowl.

- Tennessee Titans (Nissan Stadium): This stadium could be a significant player for Opportunity Zone investment, in which the stadium will require “$293.2 million in capital improvements over the next 20 years to remain viable.”

- Washington Football Club (FedExField): The team’s current lease expires in 2027, which could create an opportunity for new stadium construction.

-

-

ii. Adjacent to an Opportunity Zone

-

-

-

- Green Bay Packers (Lambeau Field): The NFL’s second oldest stadium, Lambeau Field recently saw a $130 million Titletown district built around the stadium. However, there is land east of the stadium that falls within an Opportunity Zone despite the stadium and Titletown not being in an Opportunity Zone. Thus, this land area could start a new wave of development.

- Los Angeles Rams and Chargers (SoFi Stadium): There is a tract of land situated southwest to the stadium that sits in an Opportunity Zone. Development could occur on that tract to benefit the stadium, which will host the 2022 Super Bowl and the 2028 Olympics.

- Miami Dolphins (Hard Rock Stadium): Despite the stadium recently completing a $350 million renovation project, there are adjacent parking lots both north and west of the stadium that were designated as Opportunity Zones.

-

-

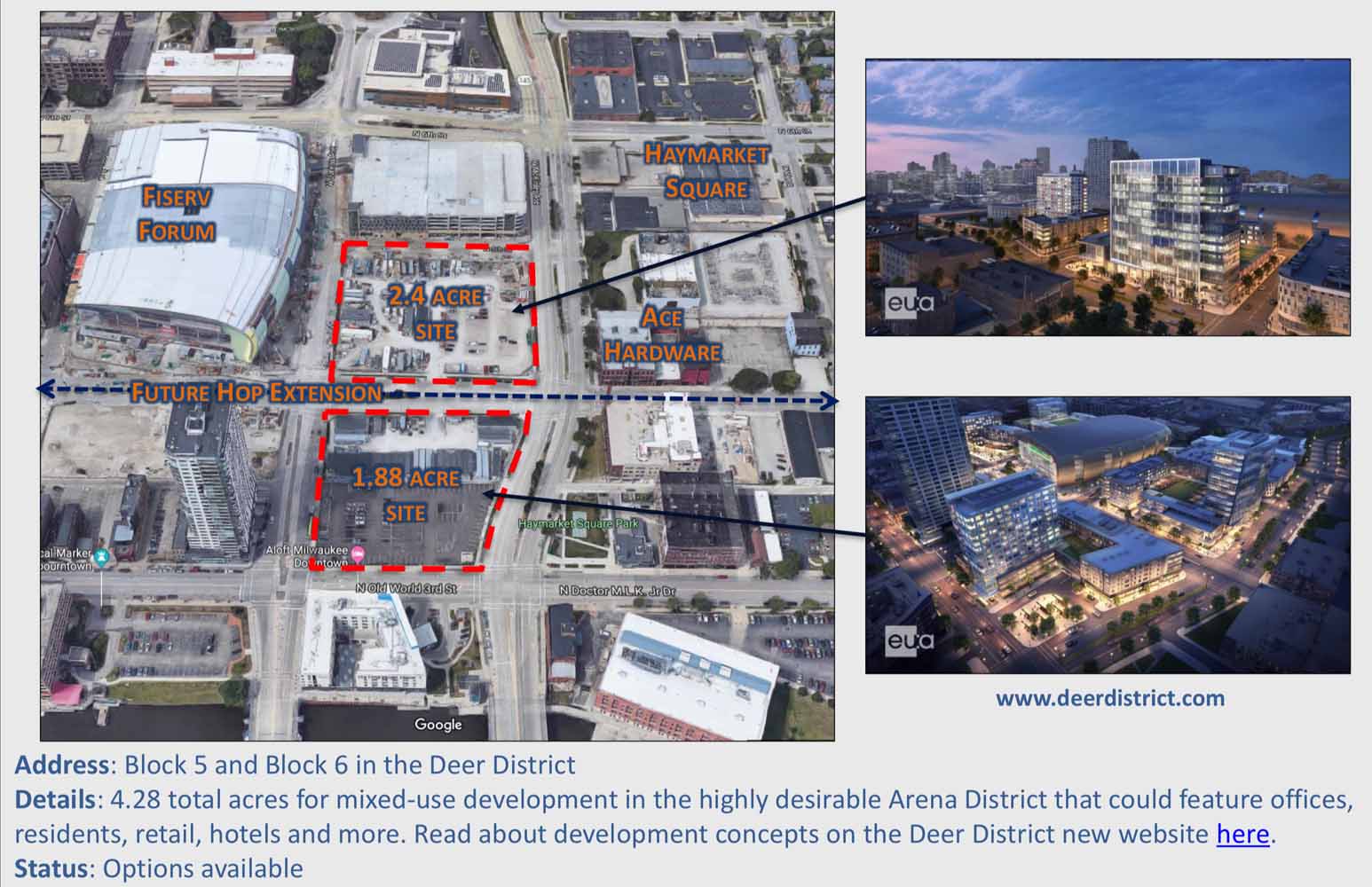

D. Sports Industry Opportunity Fund Highlight: Fortuitous Partners Opportunity Fund

One noteworthy opportunity fund that can be a major player in the sports industry is the Fortuitous Partners Opportunity Fund.[189] The Fund is managed by Fortuitous Partners, a real estate development firm in Arizona.[190] The Fund’s purpose is to invest in “professional sports-anchored multi-asset developments in Opportunity Zones throughout the United States.”[191] The Fund’s size is $500 million and is open for investment.[192] The Fund’s principal, Brett Johnson, serves as co-chairman for a minor league soccer team, the Phoenix Rising.[193] If the team is promoted to Major League Soccer, the Phoenix Rising is aiming to relocate to a new stadium within an Opportunity Zone.[194] After seeing the Phoenix Rising’s on-field impact, such as recent postseason appearances and a 2019 regular season title, coupled with a potential off-field impact in the community, Mr. Johnson started looking at other communities that could benefit from professional soccer.[195] One such community is Pawtucket, Rhode Island.[196]

In December 2019, Fortuitous Partners unveiled plans for a $400 million development along Pawtucket’s waterfront.[197] The project is called Tidewater Landing, and it will be anchored by a 7,500-seat sports arena for a United Soccer League (USL) team.[198] “Upon completion, Tidewater Landing will comprise a soccer stadium, more than 200 housing units, 100,000 square feet of retail space, a 200-room hotel, an indoor sports event center and 200,000 square feet of office space.”[199] The development will be a P3 since the public is expected to foot 20 percent of the construction cost.[200] Tidewater Landing is considered as “the largest economic development project in the history of Pawtucket.”[201]

In December 2019, Fortuitous Partners unveiled plans for a $400 million development along Pawtucket’s waterfront.[197] The project is called Tidewater Landing, and it will be anchored by a 7,500-seat sports arena for a United Soccer League (USL) team.[198] “Upon completion, Tidewater Landing will comprise a soccer stadium, more than 200 housing units, 100,000 square feet of retail space, a 200-room hotel, an indoor sports event center and 200,000 square feet of office space.”[199] The development will be a P3 since the public is expected to foot 20 percent of the construction cost.[200] Tidewater Landing is considered as “the largest economic development project in the history of Pawtucket.”[201]

The stadium for this project is not located in an Opportunity Zone, but the Division Street development and the Apex mall space are located within an Opportunity Zone, which make up much of the shopping, dining, residential and commercial real estate features and attractions for Tidewater Landing.[202] The proposed $400 million investment was recently reduced to $300 million with dropping one of the project’s main components due to contract negotiations for the Apex mall space and the negative financial impact of the Covid-19 pandemic.[203] However, discussions for the Apex space are ongoing since it is considered a critical gateway to downtown Pawtucket.[204] Regardless, the Tidewater project “will completely transform the area and the regional economy with new jobs, places to live for hundreds of families and millions in new tax revenue for the city and state.”[205] Current estimates are that the Tidewater project will bring about 1,000 permanent jobs and 2,500 construction jobs, and the project will generate $130 million in revenue annually.[206] This absolutely falls in line with the goals of Opportunity Zones in terms of job creation and an economic boost.

Tidewater Landing has three main components: (1) USL stadium; (2) Lifestyle Center; and (3) Indoor Event Center and Hotel.[207] The Pawtucket riverfront, which has been underutilized, will consist of infrastructure and development that will transform the riverfront into a vibrant, pedestrian friendly community.[208] For example, a pedestrian bridge will be constructed to reconnect Pawtucket to its riverfront.[209] Some of the key features from the original proposal included an indoor sports event center, a 200-room hotel, commercial office space totaling 200,000 square feet, and mixed-use development “with more than 200 housing units and 100,000 square feet of retail, food and beverage, and other community space.”[210] Some changes were made recently with downsizing the investment due to Covid-19, including reducing office space and adding more multi-family housing since the demand for office space is low.[211]

Tidewater Landing has three main components: (1) USL stadium; (2) Lifestyle Center; and (3) Indoor Event Center and Hotel.[207] The Pawtucket riverfront, which has been underutilized, will consist of infrastructure and development that will transform the riverfront into a vibrant, pedestrian friendly community.[208] For example, a pedestrian bridge will be constructed to reconnect Pawtucket to its riverfront.[209] Some of the key features from the original proposal included an indoor sports event center, a 200-room hotel, commercial office space totaling 200,000 square feet, and mixed-use development “with more than 200 housing units and 100,000 square feet of retail, food and beverage, and other community space.”[210] Some changes were made recently with downsizing the investment due to Covid-19, including reducing office space and adding more multi-family housing since the demand for office space is low.[211]

As for the sports.comm component of Tidewater Landing, the soccer stadium will be the focal point that the Tidewater project is built around.[212] There is sincere enthusiasm for professional soccer in Rhode Island as it “is among the Top 10 markets for televised soccer in the country, and the largest market without a professional soccer franchise.”[213] Mr. Johnson from Fortuitous Partners was able to acquire an exclusive right to bring a USL team to Rhode Island.[214] In addition to soccer games, the soccer stadium has plans to be used year-round.[215] With its rectangular shape, the stadium can accommodate other sports such as football, lacrosse, and rugby, and the stadium can host non-sporting events like concerts and festivals.[216] In terms of entertainment affordability for consumers, the price of attending a soccer game would be reasonable and affordable.[217] The average income for a Pawtucket family is $44,909, and the cost of attending a USL game could start as little as $8 and on average of $22 based on Phoenix Rising’s ticket figures.[218] Also, residents will benefit as the Tidewater Landing developers are committed to constructing workforce housing in the project area.[219] Additionally, a future Pawtucket/Central Falls train station will provide residents and visitors an opportunity to connect to mass transit and travel seamlessly.[220] By building a community around the stadium along with the above-mentioned office space, residential units, shopping, and dining and entertainment, Pawtucket will have the ideal sports.comm where people, can live, work, and play within the community.

As previously stated, the Tidewater Landing project will be considered a P3 since private and public funding are involved. The private contributions are likely to be from outside capital investments, such as Opportunity Zone investments. As for the public contribution for Tidewater Landing, tax incremental financing (TIF) will be used to pay for the project’s revenue bond financing for the project’s infrastructure.[221] A TIF acts as a subsidy by diverting a portion of the TIF’s tax revenue to help finance a project.[222] State governments authorize TIFs and the local governments administer the TIFs.[223] The local government designates an area for development, which is called a TIF district.[224] The Tidewater project will utilize the new TIF legislation “to capture new tax revenue that will be created by the project to help pay any project related bonds.”[225] Existing taxes that can be reinvested include hotel taxes, sales taxes, and real estate taxes.[226]

As previously stated, the Tidewater Landing project will be considered a P3 since private and public funding are involved. The private contributions are likely to be from outside capital investments, such as Opportunity Zone investments. As for the public contribution for Tidewater Landing, tax incremental financing (TIF) will be used to pay for the project’s revenue bond financing for the project’s infrastructure.[221] A TIF acts as a subsidy by diverting a portion of the TIF’s tax revenue to help finance a project.[222] State governments authorize TIFs and the local governments administer the TIFs.[223] The local government designates an area for development, which is called a TIF district.[224] The Tidewater project will utilize the new TIF legislation “to capture new tax revenue that will be created by the project to help pay any project related bonds.”[225] Existing taxes that can be reinvested include hotel taxes, sales taxes, and real estate taxes.[226]

Overall, the Fortuitous Partners Opportunity Fund provides an avenue of funding for sports facility and sports.comm projects within Opportunity Zones. With at least a $300 million project investment, along with the commitment to bring a professional soccer team to Pawtucket, Tidewater Landing has the ability to turn into a significant sports.comm despite not being affiliated with a major North American professional sports franchise. The project will create a community that will allow people to work and live in one area, and the project will generate jobs and spur economic development in Pawtucket. Tidewater Landing shows the ability to couple an Opportunity Zone investment with another financing method (TIFs) to allow for a more attractive investment and tips the scale for more private funding and less public funding.