In the case of Regional Convention and Sports Complex Authority v. City of St. Louis, Regional Convention and Sports Complex Authority (RSA) is seeking court clarification on what it called an “overly broad” 2002 ordinance that requires a public vote to approve the use of any City of St. Louis (St. Louis) funds for the development of professional sports facilities, which RSA says is hampering the process for crafting a financing plan to build a new National Football League (NFL) stadium (New Stadium) being proposed on the north riverfront.[1]

In its pleadings, the RSA stated that “[t]he city ordinance in overly broad, vague and ambiguous terms purports to contain restrictions on the power of the city (and many other legally separate entities) to provide ‘financial assistance’ to the development of a professional sports facility.”[2] The RSA is seeking to have the court void the St. Louis ordinance for being too vague or for violating the Missouri Constitution on grounds that it attempts to regulate legal entities separate from St. Louis and that it seeks to impose voter requirements in certain types of financing in contravention of existing statutes.[3]

Section 67.653.1(1) of Missouri’s Revised Statutes states that the RSA shall have the power:

To acquire by gift, bequest, purchase, lease or sublease from public or private sources and to plan, construct, operate and maintain, or to lease or sublease to or from others for construction, operation and maintenance, convention centers, sports stadiums, field houses, indoor and outdoor convention, recreational, and entertainment facilities and centers, playing fields, parking facilities and other suitable concessions, and all things incidental or necessary to a complex suitable for all types of convention, entertainment and meeting activities and for all types of sports and recreation, either professional or amateur, commercial or private, either upon, above or below the ground, except that no such stadium, complex or facility shall be used, in any fashion, for the purpose of horse racing or dog racing, and any stadium, complex or facility newly constructed by the authority shall be suitable for multiple purposes and designed and constructed to meet National Football League franchise standards and shall be located adjacent to an existing convention facility.[4]

In its Counterclaim, St. Louis argues that the RSA lacks the statutory authority to construct and finance the proposed new professional sports facility because the proposed new professional sports facility is not “adjacent to an existing convention facility.”[5]

In 1991, contemporaneously with the execution of the agreement to construct the Edward Jones Dome, the RSA issued three series of revenue bonds to provide funds to finance the Dome (RSA bonds), with debt service payments to be made by St. Louis, St. Louis County, and the State of Missouri. In 1993, consistent with section 67.657 Missouri’s Revised Statutes, St. Louis voters approved a three-and-a-half percent (3½%) hotel/motel tax to support the city’s payment obligations with respect to the RSA bonds.[6]

Plaintiff alleges that the plan for the construction and financing of the proposed new professional sports facility includes contributions by St. Louis to the cost of the New Stadium complex consisting of the following:

(i) the City causing the issuance of bonds[7] (the “City’s New Stadium Bonds”) with an annual debt service obligation of the City not in excess of six million dollars ($6,000,000)[8] less amounts owed as Preservation Payments on the RSA Bonds for the Dome (the “City’s RSA Dome Bonds”) with the proceeds of the City’s New Stadium Bonds being used (A) to provide for the payment in full (defease) the City’s RSA Dome Bonds and (B) as a lease payment to the RSA which it could use for the development and construction of the New Stadium or to provide for the purchase of the Dome from the RSA (which amount the RSA could use for the development and construction of the New Stadium);

(ii) the City causing the donation to the RSA of land and related property at the site of the New Stadium;

(iii) the City providing tax increment financing, transportation development financing, community improvement district financing, or other tax abatement or economic incentives deemed appropriate by the City, in connection with the development of the New Stadium; and

(iii) the City providing tax increment financing, transportation development financing, community improvement district financing, or other tax abatement or economic incentives deemed appropriate by the City, in connection with the development of the New Stadium; and

(iv) the City providing or allowing services and governmental approvals to the New Stadium routinely furnished by the City for the development, safety and security of real estate development sites in the City including, without limitation, police, fire, water, electricity, gas, and the issuance of building and occupancy and other permits or approvals.[9]

Altogether St. Louis is expected to contribute less than fifteen percent (15%) of the total project costs. Private investment would account for at least $450 million. The RSA has revealed plans for a 64,000 seat multi-purpose facility that meets current NFL franchise standards while also attempting to revitalize the north riverfront area of St. Louis.[10]

At issue is the validity of the City Ordinance 66509, which provides in part as follows:[11]

3.91.020- Procedures.

Before the City can act, by ordinance or otherwise, to provide financial assistance to the development of a professional sports facility, the following procedures must be fully implemented:

- A fiscal note must be prepared by the Comptroller, received by the governing body, and made available to the public for at least 20 days prior to final action. The fiscal note shall state the total estimated financial cost, together with a detailed estimated cost, to the City, including the value of any services, of the proposed action, and shall be supported with an affidavit by the Comptroller that the Comptroller believes the estimate is reasonably accurate.

- A public hearing must be held by the governing body allowing reasonable opportunity for both proponents and opponents to be heard. Notice of the hearing shall be published three consecutive times in two newspapers of general circulation, not less than ten days before the hearing.

3.91.030- Voter Approval Required.

No financial assistance may be provided by or on behalf of the City to the development of a professional sports facility without the approval of a majority of the qualified voters of the City voting thereon. Such voter approval shall be a condition precedent to the provisions of such financial assistance. [12]

“Financial assistance” is defined in section 3.91.010.3 as

any City assistance of value, direct or indirect, whether or not channeled through an intermediary entity, including but not limited to, tax reduction, exemption, credit, or guarantee against or deferral of increase; dedication of tax or other revenues, tax increment financing; issuance, authorization, or guarantee of bonds; purchase or procurement of land or site preparation; loans or loan guarantees; sale or donation or loan of any City resource or service; deferral, payment, assumption or guarantee of obligations, and all other forms of assistance of value.[13]

“Governing body” is defined in section 3.91.010.6 as

the entity which, or official who, proposes to take action to provide financial assistance to the development of a professional sports facility. For example, ‘governing body’ includes the Board of Aldermen, the Board of Estimate and Apportionment, the Treasurer, the Comptroller, the Director of the Community Development Agency, and the Board of Commissioners of the Planned Industrial Expansion Authority.[14]

The Ordinance, which has a purpose clause but no specific title, was enacted in 2002 pursuant to Article V of the Charter of the City of St. Louis, which specifically authorizes the adoption of ordinances directly by the people through the initiative procedure. Section 6 of Article V of the Charter states that “No ordinance adopted at the polls under the initiative shall be amended or repealed by the board of aldermen except by vote of two-thirds of all the members, nor within one year after its adoption.” The Ordinance, which has no accompanying regulations, has never been amended or repealed.[15]

The RSA argued three main points to Judge Thomas Frawley (Frawley) concerning the ordinance: 1) the RSA statutes were a matter of state law in creating the agency, and, thus, preempted the city ordinance; 2) the ordinance conflicted with state laws and even with St. Louis’s own charter; and 3) the Ordinance was unconstitutionally vague.[16]

As to the issue of vagueness, Frawley agreed, calling sections of the ordinance “too vague to be enforced” in his ruling.[17] Frawley cited prior Missouri case law, stating that vagueness, in the context of ordinance interpretation, applies where people “must guess at its meaning would differ as to its application,” or if the ordinance is “incapable of rational enforcement.”[18] Frawley went on to state that while the ordinance is clear as to legislative intent, it provided no guidance on “when, how or by whom the issue of St. Louis’s financial assistance to development of the proposed new professional sports facility will be submitted to a public vote.

“Development” is one uncertain term, as it fails to address what constitutes development; is it an idea? Are St. Louis investigations into feasibility of a stadium, internal discussions with officials, scouting locations, and other pre-construction issues subject to voter approval?[19]

“Financial assistance” is another ambiguous term. While the Ordinance defined it as “any city assistance of value, direct or indirect, whether or not channeled through an intermediary,” Frawley remained unconvinced that the above definition could be effectively enforced. “Financial assistance,” per the ordinance, includes tax increment financing (TIF), transportation development district (TDD) financing, and community improvement district (CID) financing, which is already preempted by state law.[20] Additionally, he pointed to so many “uncertainties” in the law, stating that “their sum makes a task for us, which at best could be only guesswork.”[21] Finally, Frawley notes that there is no ordinance guidance as to what exactly will be submitted to the voters for approval. Will the citizenry be voting on whether to allow carte blanche financial assistance, or must the assistance be of a specific type?[22]

Finally, the ruling held that the Ordinance was vague as to who would be preparing any ballot measure for voter approval. While the Ordinance “clearly directed the comptroller to prepare the fiscal note and the governing body to conduct the public hearing,” it is silent as to delegating duties related to preparation of ballot measures, and who would determine dates for submission of said measures.[23] Further, although the Ordinance listed certain officials and entities as examples of the governing body, it left another layer of ambiguity as the Ordinance fails to clarify which of the officials controls in this situation.

As to the Ordinance being preempted by state statute, Frawley was unconvinced by the RSA’s arguments and noted that the RSA failed to identify any section in the RSA statutes mandating St. Louis enter into agreements with the RSA.[24] The statutes merely authorized, not mandated, St. Louis and the RSA to “enter into contracts, agreements, leases and subleases with each other.”[25] Thus, the statutes did not provide a “comprehensive scheme for constructing and financing a new professional sports facility in the Metropolitan St. Louis area and, therefore, do not preempt the Ordinance.”[26]

The RSA also argued that because the RSA state statutes do not require a public vote prior to St. Louis providing financing for a new sports facility, the Ordinance stands in direct conflict with state law and must be preempted by the latter.[27] Frawley agreed here, noting that several state statutes limited their “requirements for all cases to their own prescriptions and, therefore, preempt the portions of the Ordinance that require city-wide voter approval before St. Louis may provide TIF, TDD, and CID financing.”[28]

St. Louis’s arguments centered on showing that the law that created the RSA simply said what it had the power to do, and that it was City law that controlled its own legislative processes.[29] Additionally, St. Louis, in its Counterclaim, argued the RSA lacked statutory authority to construct the new stadium because the state statute giving authority to RSA for stadium construction required said construction to be “adjacent” to the old one.[30]

However, Frawley remained skeptical of the ordinance itself and simply could not get past the vagueness inherent in the Ordinance language.[31] As to the definition of “adjacent,” Frawley articulated that Missouri courts had commonly defined it as “near or close at hand,” and not necessarily touching each other or immediately next to each other.[32] Additionally, “adjacent property” was held to “include property that is located across intersections and roads,” and nothing of the same kind intervening, i.e. another property or independent piece of land.[33]

The ruling has brought out opinions on both sides of the stadium debate. Governor Jay Nixon seemed to express agreement with the ruling, and boasted about future potential job growth and private investment that would be brought to the St. Louis area.[34] Meanwhile, Fred Lindecke, who helped pass the Ordinance, expressed his anger at Frawley’s ruling, implying that the ruling went against the wishes of the people.[35]

One of the more insightful commentaries on the decision came from St. Louis Magazine writer Ray Hartmann (Hartmann), who pointed out that “the RSA was established for one project and one project alone. The notion that former Gov. John Ashcroft and the legislature intended to create a perpetual stadium-funding machine is ludicrous.”[36] Hartmann opined that while Frawley’s legal analysis was spot on, it amounted to the RSA winning on a technicality.[37] Hartmann went on to point out in rather tongue-and-cheek fashion that City Counselor Winston Calvert might have lost his job if St. Louis prevailed on its opposition, due to St. Louis Mayor Francis Slay making the stadium deal a top economic priority of his administration. It made it next to impossible for St. Louis to litigate from a position that it itself disagreed with.[38]

An appeal to the decision has been filed in the Missouri Court of Appeals, Eastern District, by St. Louis University School of Law professor John Ammann (Ammann), who represents St. Louis residents.[39] Ammann argues that Frawley erred in denying Ammann’s motion to intervene, because St. Louis could not be trusted to defend its own ordinance, and further, the interests of the citizenry. Ammann points to St. Louis’s decision not to appeal as proof.[40] Further, Ammann argues that Frawley incorrectly deemed the ordinance vague, and misinterpreted the term “adjacent.”[41] Although he has asked for an expedited appeals process, a decision is not expected for a few months, even in a best-case scenario.[42]

After the Frawley decision, a former state representative who was an architect of St. Louis’s now-invalidated stadium funding ordinance has asked the St. Louis Board of Aldermen to take swift action to create a new one:[43]

“We are requesting that you support a new ordinance that will place financing for a new stadium on the ballot for a public vote,” wrote Jeanette Mott Oxford in a letter accompanying a draft ordinance delivered to St. Louis aldermen this morning.

“We also hope you will vote quickly to require the Comptroller to prepare a fiscal note regarding the planned expenditure of city funds, and to establish a series of public hearings on the issue,” Oxford wrote. “That way the public will be reassured it will have a role in this process, even prior to a public vote.”

Regardless of the jurisprudential value of Frawley’s ruling, it appears that the RSA has secured a major victory in removing an obstruction to the public funding necessary to build a new stadium for the Rams; whether it results in the Rams ownership group choosing to stay in St. Louis or moving west to Los Angeles remains to be seen.

The legal victory comes at an uncertain time for the Rams in St. Louis. Rams owner, Stan Kroenke (Kroenke), announced in January of 2015 that he planned to build an NFL stadium in Inglewood, California, which could pave the way for the NFL’s return to the

The legal victory comes at an uncertain time for the Rams in St. Louis. Rams owner, Stan Kroenke (Kroenke), announced in January of 2015 that he planned to build an NFL stadium in Inglewood, California, which could pave the way for the NFL’s return to the

City of Los Angeles. Kroenke bought a sixty acre tract of land in Inglewood, California.[44] “The land is located between the recently renovated Forum and the Hollywood Park racetrack, which was shut down in December, 2014, and could potentially serve as the home of a future NFL stadium,” ESPN said.[45] Further, Kroenke has joined forces with the owners of the approximately 300-acre Hollywood Park site, Stockbridge Capital Group.[46] In partnership they plan to add an 80,000 seat NFL stadium and a 6,000 seat performance venue to the already massive development of retail, office, hotel, and residential spaces.[47] Kroenke, a billionaire, has the resources to privately finance a new stadium without public assistance.[48]

When the Rams moved from Los Angeles to St. Louis in 1995 they executed a 30-year lease agreement with the St. Louis Convention & Visitors Commission (CVC) that required the stadium, now known as the Edward Jones Dome, to remain in the top 25% of stadiums in the NFL, a so called “State of the Art” clause.[49] Under the State of the Art clause, the Rams demanded improvements and in response the CVC put forward a plan that would cost $124 million.[50] The cost of the Rams’ plan was $700 million, more than half a billion more dollars than the CVC was willing to let the taxpayers shoulder.[51] The matter went to arbitration and in February of 2013 an arbitrator handed the Rams a victory. The arbitrators decided that upgrades of the magnitude outlined by the Rams would be required to make the Edward Jones Dome within the league top eight stadiums in the NFL.[52] The CVC has informed the Rams in July of 2013 that it would not undertake the $700 million upgrade that was requested.[53] As a result, the Rams have the option of ending their 30-year lease a decade early.[54] The arbitrator’s decision allows the Rams to break their lease with the Dome after the 2014 season.[55] In January of 2015 the Rams sent a letter to the CVC indicating that the team was converting its 30-year lease to an annual tenancy effective April 1st, and in the absence of intervening events, extending through March 31, 2016.[56]

When the Rams moved from Los Angeles to St. Louis in 1995 they executed a 30-year lease agreement with the St. Louis Convention & Visitors Commission (CVC) that required the stadium, now known as the Edward Jones Dome, to remain in the top 25% of stadiums in the NFL, a so called “State of the Art” clause.[49] Under the State of the Art clause, the Rams demanded improvements and in response the CVC put forward a plan that would cost $124 million.[50] The cost of the Rams’ plan was $700 million, more than half a billion more dollars than the CVC was willing to let the taxpayers shoulder.[51] The matter went to arbitration and in February of 2013 an arbitrator handed the Rams a victory. The arbitrators decided that upgrades of the magnitude outlined by the Rams would be required to make the Edward Jones Dome within the league top eight stadiums in the NFL.[52] The CVC has informed the Rams in July of 2013 that it would not undertake the $700 million upgrade that was requested.[53] As a result, the Rams have the option of ending their 30-year lease a decade early.[54] The arbitrator’s decision allows the Rams to break their lease with the Dome after the 2014 season.[55] In January of 2015 the Rams sent a letter to the CVC indicating that the team was converting its 30-year lease to an annual tenancy effective April 1st, and in the absence of intervening events, extending through March 31, 2016.[56]

Governor Jay Nixon has formed a Task Force to develop plans for an NFL stadium project on the north river front of downtown St. Louis that could be the new home for the St. Louis Rams, as well as related enhancements to the Edward Jones Dome and America Center Convention facilities. The Task Force is lead by Dave Peacock, a former Anheuser-Busch executive and Bob Blitz, a St. Louis attorney.[57]

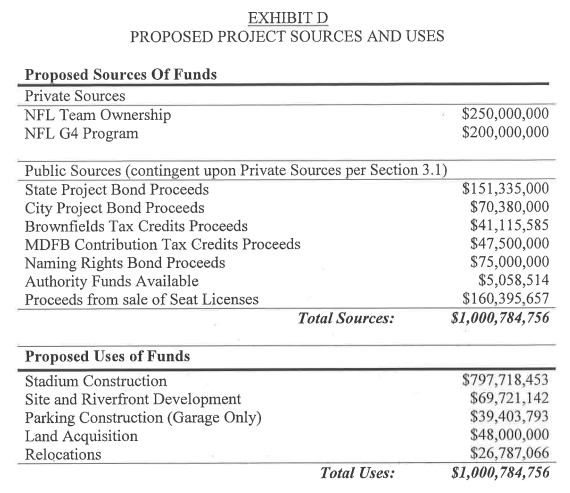

In October of 2015, the Task Force released its stadium project proposal (St. Louis Riverfront Stadium Project Financing, Construction and Lease Agreement), which was presented at a meeting of NFL owners in New York City on November 11, 2015. The proposed project use of funds and sources of funds are as hereinafter stated: [58]

National Car Rental, which is owned by Enterprise Holdings–one of the largest corporations in St. Louis–has agreed to pay $158 million for the naming rights to a new football stadium to be called National Car Rental Field, payable over a twenty year period. The deal, which was announced in October of 2015, is designed to show the thirty-two NFL owners that St. Louis and the State of Missouri can pay for the one billion dollar stadium that they hope to build if the Rams or another team agree to play there.[59]

The NFL has publicly questioned the public sources of funds wherein Naming Rights Bond Proceeds in the amount of $75 million would be used as public sources of funds.[60] The NFL considers naming right money property of the team, and it also considers the game-day tax rebate that St. Louis is proposing to pay back the Rams for use of the naming rights property of the team as well.[61] Once again the $75 million Naming Rights Bond Proceeds would come from St. Louis financing the $158 million naming rights deals with National Car Rental.[62]

The NFL has publicly questioned the public sources of funds wherein Naming Rights Bond Proceeds in the amount of $75 million would be used as public sources of funds.[60] The NFL considers naming right money property of the team, and it also considers the game-day tax rebate that St. Louis is proposing to pay back the Rams for use of the naming rights property of the team as well.[61] Once again the $75 million Naming Rights Bond Proceeds would come from St. Louis financing the $158 million naming rights deals with National Car Rental.[62]

Commissioner Roger Goodell has made it clear that the NFL does not want to relocate franchises. The legal and governmental entanglements and ill-will that result from such moves could conceivably cause the NFL to lose some of the power and influence it possesses.[63]

Section 4.3 of Article 4 of the NFL Constitution provides that three-quarters (3/4) of its league members must approve any request to relocate a franchise before relocation can occur. (“The League shall have exclusive control of the exhibition of football games by member clubs within the home territory of each member. No member club shall have the right to transfer its franchise or playing site to a different city, either within or outside its home territory, without prior approval by the affirmative vote of three-fourths of the existing member clubs of the League.”[64])

What follows are some of the rules and policies of the NFL relating to relocation:

Because League policy favors stable team-community relations, clubs are obligated to work diligently and in good faith to obtain and to maintain suitable stadium facilities in their home territories, and to operate in a manner that maximizes fan support in their current home community…If, having diligently engaged in good faith efforts, a club concludes that it cannot obtain a satisfactory resolution of its stadium needs, it may inform the League Office and the stadium landlord or other relevant public authorities that it has reached a stalemate in those negotiations. Upon such a declaration, the League may elect to become directly involved in the negotiations. (Article 4.3, Section A)

No club has an “entitlement” to relocate simply because it perceives an opportunity for enhanced club revenues in another location. Indeed, League traditions disfavor relocations if a club has been well-supported and financially successful and is expected to remain so. Relocation pursuant to Article 4.3 may be available, however, if a club’s viability in its home territory is threatened by circumstances that cannot be remedied by diligent efforts of the club working, as appropriate, in conjunction with the League Office, or if compelling League interests warrant franchise relocation. (Article 4.3)

In considering a proposed relocation, the Member Clubs are making a business judgment concerning how best to advance their collective interests. Guidelines and factors such as those identified below are useful ways to organize data and to inform that business judgment. They are intended to assist the clubs in making a decision based on their judgment and experience, and taking into account those factors deemed relevant to and appropriate with regard to each proposed move. Those factors include:

- The extent to which the club has satisfied, particularly in the last four years, its principal obligation of effectively representing the NFL and serving the fans in its current community; whether the club has previously relocated and the circumstances of such prior relocation;

- The extent to which fan loyalty to and support for the club has been demonstrated during the team’s tenure in the current community;

- The adequacy of the stadium in which the club played its home games in the previous season; the willingness of the stadium authority or the community to remedy any deficiencies in or to replace such facility, including whether there are legislative or referenda proposals pending to address these issues; and the characteristics of the stadium in the proposed new community;

- The extent to which the club, directly or indirectly, received public financial support by means of any publicly financed playing facility, special tax treatment, or any other form of public financial support and the views of the stadium authority (if public) in the current community;

- The club’s financial performance, particularly whether the club has incurred net operating losses (on an accrual basis of accounting), exclusive of depreciation and amortization, sufficient to threaten the continued financial viability of the club, as well as the club’s financial prospects in its current community;

- The degree to which the club has engaged in good faith negotiations (and enlisted the League office to assist in such negotiations) with appropriate persons concerning terms and conditions under which the club would remain in its current home territory and afforded that community a reasonable amount of time to address pertinent proposals;

- The degree to which the owners or managers of the club have contributed to circumstances which might demonstrate the need for such relocation. (Article C)[65]

The NFL is dead set to return to Los Angeles after a twenty-one (21) year absence and to recapture the second largest TV market in the United States.

Many questions abound as to the future of the Rams as to their stay in St. Louis or their relocation to Los Angeles, including:

- Will the NFL owners, even though public money is being put on the table and a Rams stadium plan – although not perfect – is in place, permit the Rams to relocate?

- Is Los Angeles a two franchise market?

- The Commissioner has established a Committee on L.A. Opportunities. Does Kroenke have the twenty-four votes that he needs to relocate or in the alternative, the votes to defeat the Carson plan?

- Who will the NFL owners favor with respect to relocation? Kroenke, with a privately-funded stadium in Inglewood (with no public contribution), or the Oakland Raiders and the San Diego Chargers’ shared stadium plan in Carson, California, now headed by Disney executive, Bob Iger. Or will the League through the Commissioner’s Office manage the outcome rather than pitting NFL owners against one another to create a grand bargain?

- Does Dean Spanos, owner of the San Diego Chargers, who has been attempting to get a new stadium for fifteen years and gone through seven different mayors, have the first priority with respect to NFL Los Angeles relocation? Ultimately who has more political capital – Spanos or Kroenke?

- Will the Owners follow the NFL relocation guidelines that were not available during the 1990’s and the period of franchise free agency?

- With respect to Kroenke’s Inglewood site: The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) released a preliminary report stating that the venue at the former Hollywood Park site is “presumed to be a hazard to air navigation.” The FAA also stated that the Inglewood site could interfere with radar that is used to track incoming aircraft to Los Angeles International Airport. However the FAA report also gave solutions to the problem including relocating the stadium, reducing the height by more than 100 feet, or reshaping the exterior or covering part of the exterior surfaces with material that will absorb radar.[66]

- Would any of the owners move without approval or in the alternative sue the League much the same as Al Davis did when he removed to Oakland?

- Is it possible that the ultimate resolution will be a deal hammered out by Spanos and Kroenke?

- Is there really time enough to make a decision for the 2016 NFL campaign and could this be further delayed?

- What effect will an imposed relocation fee have upon removal, with a relocation fee estimated to be in the area of $500-600 million?

- How strongly will the NFL abide by an underlying principle relative to relocation and that is – relocation guidelines always put an emphasis on allowing the home markets to keep their franchise?

- Is relocation really about the fans or is this more about state-of-the-art stadia and valuation of team franchises, and will economics ultimately prevail?

Whatever the results, stay tuned, in that this will probably be sorted out during the months of December 2015 and January 2016, but no later than after the Super Bowl, as the NFL will be required to make some difficult decisions.

Thank you to third-year Marquette University Law School student Maximilian Rabkin for his assistance in researching and writing this article, and to third-year Marquette University Law School student Lori Shaw for her assistance in editing and footnoting.

[1] Linda Chiem, Court Asked to Weigh in on St. Louis NFL Stadium Plan, Law360 (Apr. 10, 2015), http://www.law360.com/articles/641975/court-asked-to-weigh-in-on-st-louis-nfl-stadium-plan.

[2] Id.

[3] Id.

[4] Mo. Rev. Stat. § 67.653.1 (2015).

[5] Order and Judgement, No. 1522-cc0782, 6 (2015), available at http://media.bizj.us/view/img/6611742/stadium-ii-2015.pdf.

[6] Id. at 12.

[7] Counsel for Plaintiff explained that the bonds referenced in the Petition would not be issued by the City but would be issued by RSA, with debt service payments to be made in part by the City of St. Louis.

[8] Counsel for Plaintiff represented to the Court that the revenue from the existing City hotel/motel tax is sufficient to cover the City’s debt service obligation on the proposed new bonds, that there is no commitment by the City to utilize general revenue if the revenue from the existing City hotel/motel tax is insufficient, and that the cost to the City would involve more than the revenue from the existing City hotel/motel tax only if that revenue was drastically reduced.

[9] Order and Judgment, supra note 5, at 12.

[10] Chiem, supra note 12.

[11] Order and Judgment, supra note 5, at 10.

[12] Id. at 10.

[13] Id. at 10–1.

[14] Id. at 11.

[15] Id. at 11–2.

[16] Rachel Lippmann, Fight over new NFL stadium heads to Judge Frawley (June 25, 2015), http://news.stlpublicradio.org/post/fight-over-new-nfl-stadium-heads-judge-frawley.

[17] David Hunn, Judge says no vote needed on St. Louis stadium funding; Feacock calls on region to ‘rally,’ St. Louis Post-Dispatch (Aug. 3, 2015), http://www.stltoday.com/news/local/govt-and-politics/article_51c33b67-9b72-5055-ba56-94cc9e1b46e2.html#.Vb-lI-gf8RQ.twitter.

[18] Order and Judgement, supra note 5, at 23.

[19] Id. at 24.

[20] Id. at 25.

[21] Id. at 31.

[22] Id. at 27.

[23] Id. at 28.

[24] Id. at 15–16.

[25] Id.

[26] Id.

[27] Id. at 17–18.

[28] Id. at 21.

[29] Lippman, supra note 16.

[30] Order and Judgment, supra note 5, at 6.

[31] Hunn, supra note 17.

[32] Order and Judgment, supra note 5, at 7.

[33] Id. at 8–9.

[34] Shane Gray, Gray: With RSA Ruling, Task Force Likely Cleared Largest Public Funding Hurdle, insideSTL.com (Aug. 6, 2015), http://www.insidestl.com/insideSTLcom/STLSports/STLRams/tabid/137/articleType/ArticleView/articleId/18589/Gray-With-RSA-Ruling-Task-Force-Likely-Cleared-Largest-Public-Funding-Hurdle.aspx.

[35] Id.

[36] Ray Hartmann, Why Can’t We All Be Friends?, St. Louis Magazine (Aug. 4, 2015), http://www.stlmag.com/news/sports/st-louis-stadium-project-survives-pseudo-lawsuit/.

[37] Id.

[38] Id.

[39] Jacob Kirn, City residents appeal judge’s ruling on stadium financing, St. Louis Business Journal (Aug. 11, 2015), http://www.bizjournals.com/stlouis/news/2015/08/11/city-residents-appeal-judge-s-ruling-on-stadium.html.

[40] Id.

[41] Id.

[42] Id.

[43] Nicholas J.C. Pistor, Former state rep. urges St. Louis Aldermen to pass new stadium funding ordinance, St. Louis Post-Dispatch (Aug. 27, 2015), http://www.stltoday.com/news/local/govt-and-politics/nick-pistor/former-state-rep-urges-st-louis-aldermen-to-pass-new/article_e96a8e10-8f57-582d-9cfc-b5f287dc7c2c.html.

[44] Zachary Steiber, St. Louis Rams Rumors: Relocation to Los Angeles is a Done Deal, Will be Announced After Super Bowl, Epoch Times (Oct. 2, 2014), http://www.theepochtimes.com/n3/994905-st-louis-rams-rumors-sources-say-relocation-to-los-angeles-is-a-done-deal/.

[45] Id.

[46] Sam Farmer & Roger Vincent, Owner of St. Louis Rams plans to build NFL stadium in Inglewood, Los Angeles Times (Jan. 5, 2015), http://www.latimes.com/sports/nfl/la-sp-0105-nfl-la-stadium-20150105-story.html.

[47] Id.

[48] Id.

[49] Kristen E. Knauf, If You Build It, Will They Stay? An Examination of State-of-the-Art Clauses in NFL Stadium Leases, 20 Marq. Sports L. Rev. 479, 483–4 (2010).

[50] Kelsey Proud & Rachel Lippmann, Rams Free To Leave St. Louis After 2014 Season, St. Louis Public Radio (July 5, 2013), http://news.stlpublicradio.org/post/rams-free-leave-st-louis-after-2014-season

[51] AP, Rams can break lease, ESPN.com (July 5, 2013), http://espn.go.com/espn/print?id=9452628.

[52] Proud & Lippmann, supra note 50.

[53] AP, supra note 51.

[54] Id.

[55] Proud & Lippmann, supra note 50.

[56] David Hunn, Rams to city: We’ll stay for another year, St. Louis Post-Dispatch (Jan. 27, 2015), http://www.stltoday.com/news/local/govt-and-politics/rams-to-city-we-ll-stay-for-another-year/article_c281a12a-afbb-5e1d-acd3-808c04d35497.html.

[57] St. Louis NFL Stadium Task Force, http://stlstadium.com/ (last visited Nov. 22, 2015).

[58] Alex Ihnen, DRAFT St. Louis Riverfront Stadium Project Financing, Construction and Lease Agreement, nextSTL (Oct. 23, 2015), http://nextstl.com/2015/10/draft-st-louis-riverfront-stadium-project-financing-construction-and-lease-agreement/.

[59] Ken Belson, Stadium Sponsor Unveiled in Move to Keep Rams in St. Louis, The New York Times (Oct. 6, 2015), http://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/07/sports/football/stadium-sponsor-unveiled-in-move-to-keep-rams-in-st-louis.html?_r=1.

[60] Ihnen, supra note 58.

[61] Vincent Bonsignore, From the NFL lens, St. Louis stadium plan has issues, The NFL in L.A. with Vincent Bonsignore (Nov. 6, 2015), http://www.insidesocal.com/nfl/2015/11/06/from-the-nfl-lens-st-louis-stadium-plan-has-issues/.

[62] Vincent Bonsignore, St. Louis, San Diego, Oakland get their say to NFL; but will it be last before relocation window?, The NFL in L.A. with Vincent Bonsignore (Nov. 10, 2015), http://www.insidesocal.com/nfl/2015/11/10/st-louis-san-diego-oakland-get-their-say-to-nfl-but-will-it-be-last-before-relocation-window/.

[63] Randy Karraker, NFL Relocation Rules Make Rams’ Picture Even Cloudier, 101Sports.com (Feb. 14, 2014), http://www.101sports.com/2014/02/14/nfl-relocation-rules-make-rams-picture-even-cloudier/.

[64] Constitution and Bylaws of the National Football League, art. 4, § 4.3 (2006).

[65] Karraker, supra note 63.

[66] Henry Buggy, NFL NEWS: St. Louis Rams Relocation Faces New Hurdle In Moving To Inglewood, Headlines & Global News (Nov. 11, 2015), http://www.hngn.com/articles/149348/20151111/nfl-news-st-louis-rams-relocation-faces-new-hurdle-moving.htm.